Question: each night, you like to wind down with a relaxing game of one-upsmanship against yourself, throwing darts at your bullseye one by one, trying to get each one closer than the last. When a dart lands further from the center than the one that came before, the streak is over. Over the course of your life, how many darts will you throw on the average night? Assume that all darts hit inside the bullseye and that the darts are equally likely to land at any point inside the outer ring of the dartboard. For additional credit, you can play the demented version of the game where the board is divided into $10$ annuli, and instead of trying to move closer, period, you try to get within tighter and tighter rings.

Solution

Standard credit

Let’s pretend that we have an infinite set of infinite sequences of sampled circles, $\mathcal{C}_\infty.$

Draw a sample with circles of radii $\{r_1, r_2, \ldots\}.$ The probability that it corresponds to a run of $j$ successful shots is the probability that its first $j$ circles are ordered times the probability that the $\left(j+1\right)^\text{th}$ circle is out of order:

\[P\left(j\,\text{shots}\right) = P(\text{first $j$ circles in order})\times P(r_{j+1} > r_j).\]$P(\text{first $j$ circles in order})$ is straightforward: there are $j!$ orderings of $j$ elements, only $1$ of which is in the right order. So this is just $1/j!.$

The second bit requires us to know $r_j.$ In expectation, the smallest of $n$ uniformly random numbers is just $1/(n+1).$ The reason, briefly, is that the expected positions of the smallest, second smallest, …, up to the largest are equally spaced. The probability of the $\left(j+1\right)^\text{th}$ number being greater than this is just

\[P(r_{j+1} > r_j) = \left(1 - \frac{1}{j+1}\right) = \dfrac{j}{j+1}.\]This gives

\[P\left(j\,\text{shots}\right) = \dfrac{1}{j!}\dfrac{j}{j+1}.\]The number of points won through $j$ successful shots is $\left(j+1\right),$ so

\[\begin{align} \langle S\rangle &= \sum_{j=1}^\infty \left(j+1\right) \dfrac{1}{j!}\dfrac{j}{j+1} \\ &= \sum_{j=1}^\infty \frac{1}{\left(j-1\right)!} \\ &= e. \end{align}\]Additional credit

In the demented version of the game, we use a discrete dartboard with $10$ rings of radius $\{1, 2, \ldots, 10\}.$

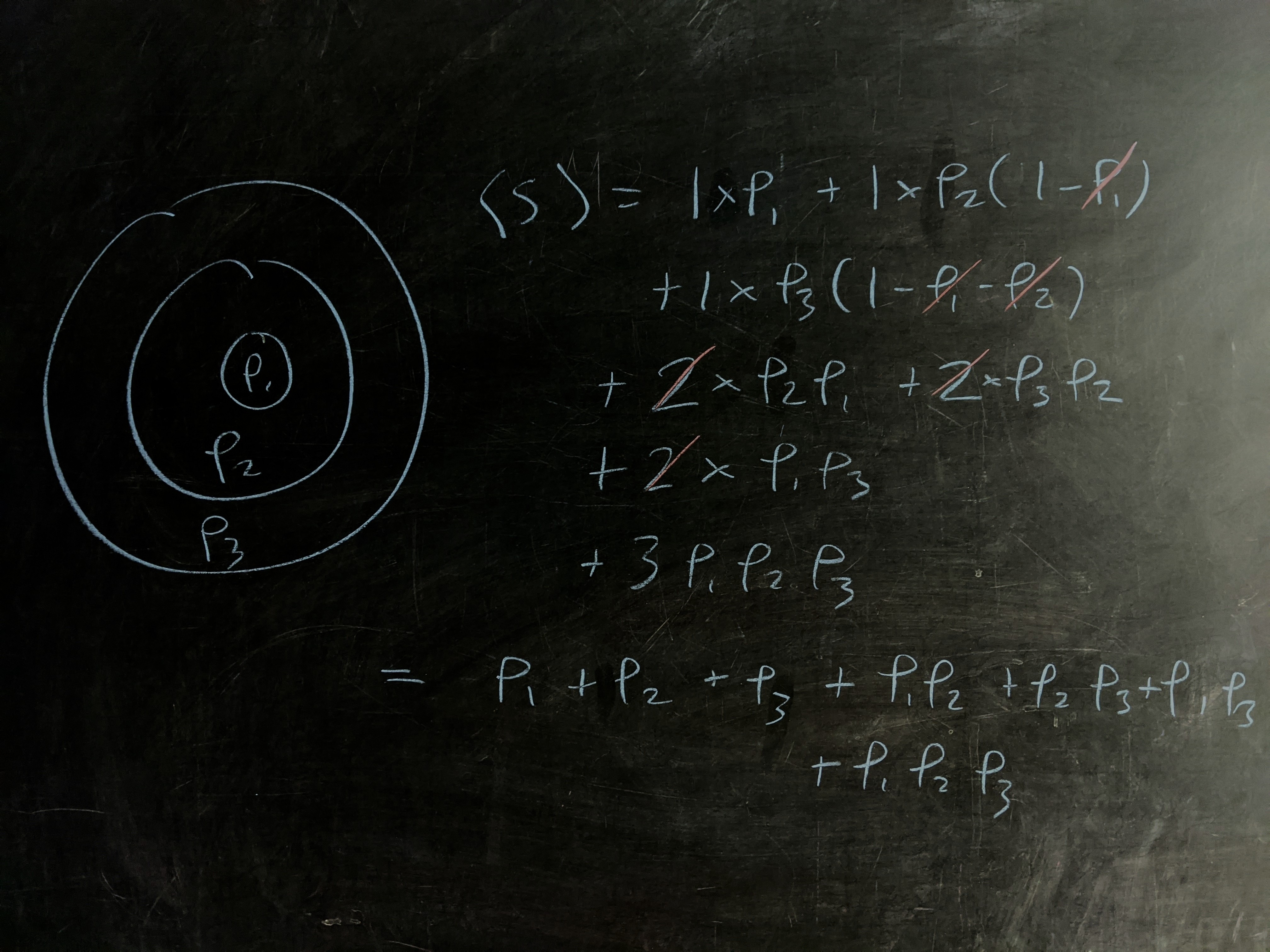

Calculating with $3$ rings, we get

\[\langle S_3\rangle = 1 + \left(p_1+p_2 + p_3\right) + \left(p_1p_2 + p_2p_3 + p_1p_3\right) + p_1p_2p_3\]Low-stakes calculation of the $3$-ring case.

We can reinterpret this like so — the second term is the total probability of making $1$ or more shots, the third term is the total probability of making $2$ or more shots, and the fourth is the total probability of making $3$ or more shots (in this case, there’s no “or more”, but for generalizing, think of it this way).

This reflects the magical connection between pdf and cdfs in calculating expected values:

\[\langle S\rangle =\sum_j j\cdot P(s = j) = \sum_j P(s \geq j).\]So, we just need to generate all possible probability stems for getting $1,$ $2,$ $\ldots,$ up to $10$ shots.

So, the expectation for $10$ rings is just

\[\boxed{\langle S\rangle = \left(1+p_1\right)\times\left(1+p_2\right)\times\cdots\times\left(1+p_{10}\right)}.\]To check, we can factor the $3$-ring example, which produces

\[\langle S\rangle = \left(1 + p_1\right)\times\left(1 + p_2\right)\times\left(1 + p_3\right),\]in line with the $10$-ring result.

Plugging in the probability of landing in the various rings,

\[p_j = \dfrac{j^2 - (j-1)^2}{10^2} = \dfrac{2j-1}{10^2},\] \[\langle S\rangle = \dfrac{10234113997905495243}{4000000000000000000} \approx 2.558528\]