Question: another day, another demented hostage situation whose only salvation is twisted hat logic. The potentate of puzzles has kidnapped, blindfolded, and placed a red, green, or blue cap upon the head of you and $4$ of your unluckiest friends. Furthermore, they’ve split you up into two rows of $3$ and $2$ apiece. On opening your eyes, you can see the colors of the hats of the people in the opposite row. With nothing more than this information, and knowledge of your own position in the arrangement, you have to guess the color of your hat. If at least one person guesses correctly you all survive, otherwise it’s time for the long nap. Is there a strategy that guarantees your survival?

Solution

If everybody guesses $\color{blue}{\text{blue}}$ for all inputs, then there will be at least one person who is correct in every case where someone has a $\color{blue}{\text{blue}}$ hat. There are just $2^5$ ways to build $\color{red}{\text{red}}$-$\color{green}{\text{green}}$ ONLY patterns, so we start off with $3^5 - 2^5 = 211$ correct guesses when the default strategy is “guess $\color{blue}{\text{blue}}$”.

Not coincidentally, this is the expected number of survival cases when everyone guesses at random, $243\times(1-(2/3)^5) = 211$.

So, we need to relocate some correct guesses from the cases that have multiple correct guesses to those that have none.

A number of good guesses

There is something startling about the guessing game: if we follow a deterministic strategy, then each player will make the same number of correct guesses across the $243$ cases, no matter what the strategy. To see this, let’s think about the information I have at my disposal depending on where I am.

If I’m in the $3$-person row, then all I see is the color status of the people in the $2$-person row, $\left(C_4, C_5\right).$ There are $9$ possibilities for this pair of colors, so I will see each of them $243/9=27$ times and make the same guess every time. Across those occasions, my color will be right in a third of the cases, making for a total of $\frac13\times9\times27 = 81$ correct guesses and $162$ wrong ones.

If I’m in the $2$-person row, then all I see is the color status of the people in the $3$-person row, $\left(C_1, C_2, C_3\right).$ There are $27$ possibilities for this pair of colors, so I will see each of them $243/27=9$ times and make the same guess every time. Across those occasions, my color will be right in a third of the cases, making for a total of $\frac13\times27\times9 = 81$ correct guesses and $162$ wrong ones.

So, each person guesses correctly $81$ times, always. This makes $5\times81=405$ total correct guesses, which is more than enough to have $1$ in each of the $243$ cases. We just need to distribute these $405$ correct guesses so that they pattern the rows.

Row life

If we only adjust the guesses of the people in the second row, then we can’t outperform the $211$ benchmark of random guessing.

Suppose we change player $4$’s strategy, which is currently \(S_4(\_, \_, \_)\rightarrow {\color{blue}{\text{B}}},\) so that \(S_4(R,R,R)\rightarrow {\color{red}{\text{R}}}.\) This will lead to a newly successful prediction in the case where $C_1, C_2, C_3,$ $C_4$ and $C_5$ are $\color{red}{\text{red}}$, but it will spoil the prediction in the case where $C_1, C_2, C_3$ and $C_5$ are $\color{red}{\text{red}}$, and $C_4$ is $\color{blue}{\text{blue}},$ negating the gain. Since player $5$ doesn’t know the value of $C_4,$ they can’t affect their strategy to compensate.

The same is true if we only adjust the strategies of the people in the first row. So, if we want to add successful predictions in currently barren cases while preserving the ones we have already, we have to make balanced changes.

What remains is to go through the $29$ other cases with no $\color{blue}{\text{blue}}$ and make compensatory adjustments so they end up with successful predictions.

Viva la evolution

We can go through this exercise, bringing the $\color{blue}{\text{blue}}$-less cases into the light, case by case, or we can turn to the guiding warmth of natural selection.

In a sense, each player’s strategy $S_i,$ is a gene whose purpose it to make effective predictions in light of the $4$ other genes. Whenever we alter what a strategy $S_i$ does in response to a particular state of the opposing row, it is a mutation.

Concretely, the strategy of a player in the first row is a function from $C^2$ to $C$:

\[S_i(C_4, C_5) \rightarrow \hat{S}_i.\]Likewise, the strategy of a player in the second row is a function from $C^3$ to $C$:

\[S_i(C_1, C_2, C_3) \rightarrow \hat{S}_i.\]When a mutation occurs, we can compare how the “organism” does with that mutation as compared to without. If we only accept mutations that have a positive impact on predictions, then we should expect the track record to improve over time.

Fig: a figurative evolutionary landscape for the problem. The $x$ and $y$ axes represent different mutations of the same strategy and the $z$ axis represents the total number of the possible $243$ cases that the corresponding strategy makes at least one successful prediction in. Whenever a strategy is mutated it can increase the number of successful cases, decrease them, or leave them unchanged. If we only accept the good or neutral improvements then we can hill climb. One deceiving aspect is that mutations have many more effective directions in which to explore, so we aren’t necessarily trapped at a local optima with respect to all moves.

However, it could be that several mutations have to occur in concert before we can expect to see a positive impact. So, we can also accept the “neutral” mutations that don’t improve, but also don’t hurt our predictions.

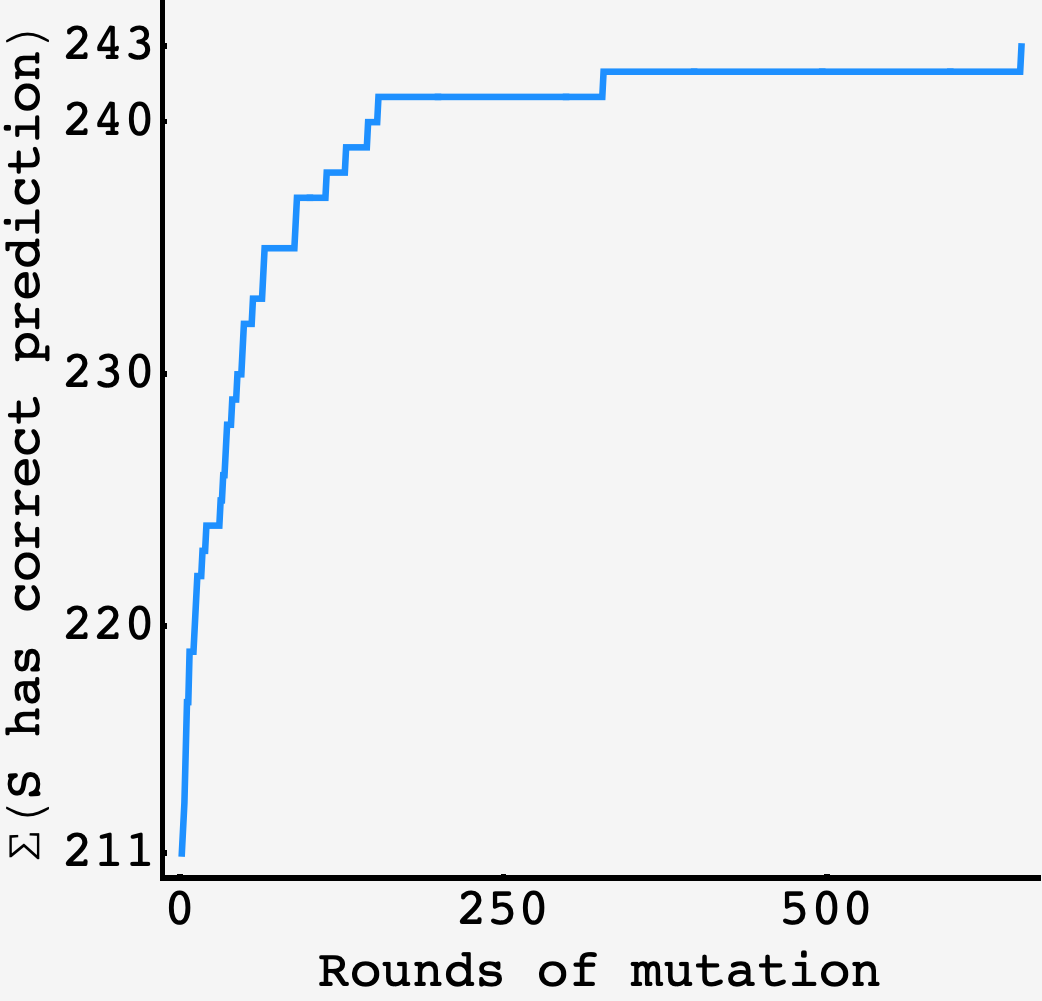

Running the evolutionary program once, we see convergence in about $\approx 800$ rounds of mutation:

At the outset, almost every mutation we attempt has a beneficial impact as it explores strategies that spread the correct predictions out of the rows that have “too many” correct predictions, where “just right” is $405/243 = 5/3$ successful predictions per row.

After the initial rise, we see the importance of neutral mutations which the organism churns through for a long time as it wanders toward the tweaks that can bring the last few cases into the fold.

Evolved strategy for players $1,$ $2,$ and $3.$

\[\begin{array}{|cc|c|c|c|} \hline C_4 & C_5 & \hat{S}_1 & \hat{S}_2 & \hat{S}_3 \\ \hline 0 & 0 & 2 & 0 & 2 \\ 0 & 1 & 2 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 2 & 2 & 2 & 0 \\ 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 2 \\ 1 & 1 & 1 & 0 & 1 \\ 1 & 2 & 1 & 0 & 2 \\ 2 & 0 & 2 & 1 & 1 \\ 2 & 1 & 0 & 2 & 1 \\ 2 & 2 & 1 & 1 & 0 \\ \hline \end{array}\]Evolved strategy for players $4$ and $5.$

\[\begin{array}{|ccc|c|c|} \hline C_1 & C_2 & C_3 & \hat{S}_4 & \hat{S}_5 \\ \hline 0 & 0 & 0 & 2 & 2 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 2 \\ 0 & 0 & 2 & 2 & 2 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 1 & 0 & 2 \\ 0 & 1 & 2 & 0 & 1 \\ 0 & 2 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 2 & 1 & 0 & 2 \\ 0 & 2 & 2 & 2 & 1 \\ 1 & 0 & 0 & 2 & 0 \\ 1 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 1 & 0 & 2 & 2 & 2 \\ 1 & 1 & 0 & 2 & 0 \\ 1 & 1 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 1 & 1 & 2 & 0 & 1 \\ 1 & 2 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 1 & 2 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 1 & 2 & 2 & 0 & 0 \\ 2 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ 2 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 2 \\ 2 & 0 & 2 & 2 & 0 \\ 2 & 1 & 0 & 1 & 1 \\ 2 & 1 & 1 & 1 & 2 \\ 2 & 1 & 2 & 1 & 1 \\ 2 & 2 & 0 & 1 & 2 \\ 2 & 2 & 1 & 1 & 2 \\ 2 & 2 & 2 & 1 & 2 \\ \hline \end{array}\]Restricted evolution

The more restrictive we make the evolutionary strategy, the longer it takes to find a solution. We could make each row into a gene, in which case we force the row to do a more disruptive mutation, which takes much longer than when we allow each player’s strategy to mutate independently. Likewise, if we only accept mutations that improve the predictions, we can easily get stuck on local optima that are better or as good as all their neighbors, but worse than none of them.

Running in this restricted mode, we can see the minimal number of necessary mutations which hovers at just under $30.$

(plot forthcoming)

The code

The code below simulates the constrained case where all three strategies mutate together, which is less visually offensive than the code that mutates each strategy individually:

import random

import copy

cases = [[a,b,c,d,e] for a in range(3)

for b in range(3)

for c in range(3)

for d in range(3)

for e in range(3)]

predUp = {tuple(case[3:]) : [0, 0, 0] for case in cases}

predLow = {tuple(case[0:3]) : [0, 0] for case in cases}

def testRows(predUp, predLow):

successes = 0

for case in cases:

predictions = predUp[tuple(case[3:])] + predLow[tuple(case[0:3])]

if any(case[i] == predictions[i] for i in range(5)):

successes += 1

return successes

current_best_score = 0

joint_record = []

while current_best_score < 243:

# Pick the cases to mutate

upper_key_to_mutate = random.choice(list(predUp.keys()))

lower_key_to_mutate = random.choice(list(predLow.keys()))

# Copy the current strategies

(tmp_predUp, tmp_predLow) = (copy.deepcopy(predUp), copy.deepcopy(predLow))

# Pick the new predictions for the two selected cases

tmp_predUp[upper_key_to_mutate] = random.choices([0,1,2], k=3)

tmp_predLow[lower_key_to_mutate] = random.choices([0,1,2], k=2)

# Count the number of successful predictions of mutated strategy

test_score = testRows(tmp_predUp, tmp_predLow)

# Accept the mutatations if they don't hurt

if test_score >= current_best_score:

current_best_score = test_score

(predUp, predLow) = (tmp_predUp, tmp_predLow)

joint_record.append(current_best_score)