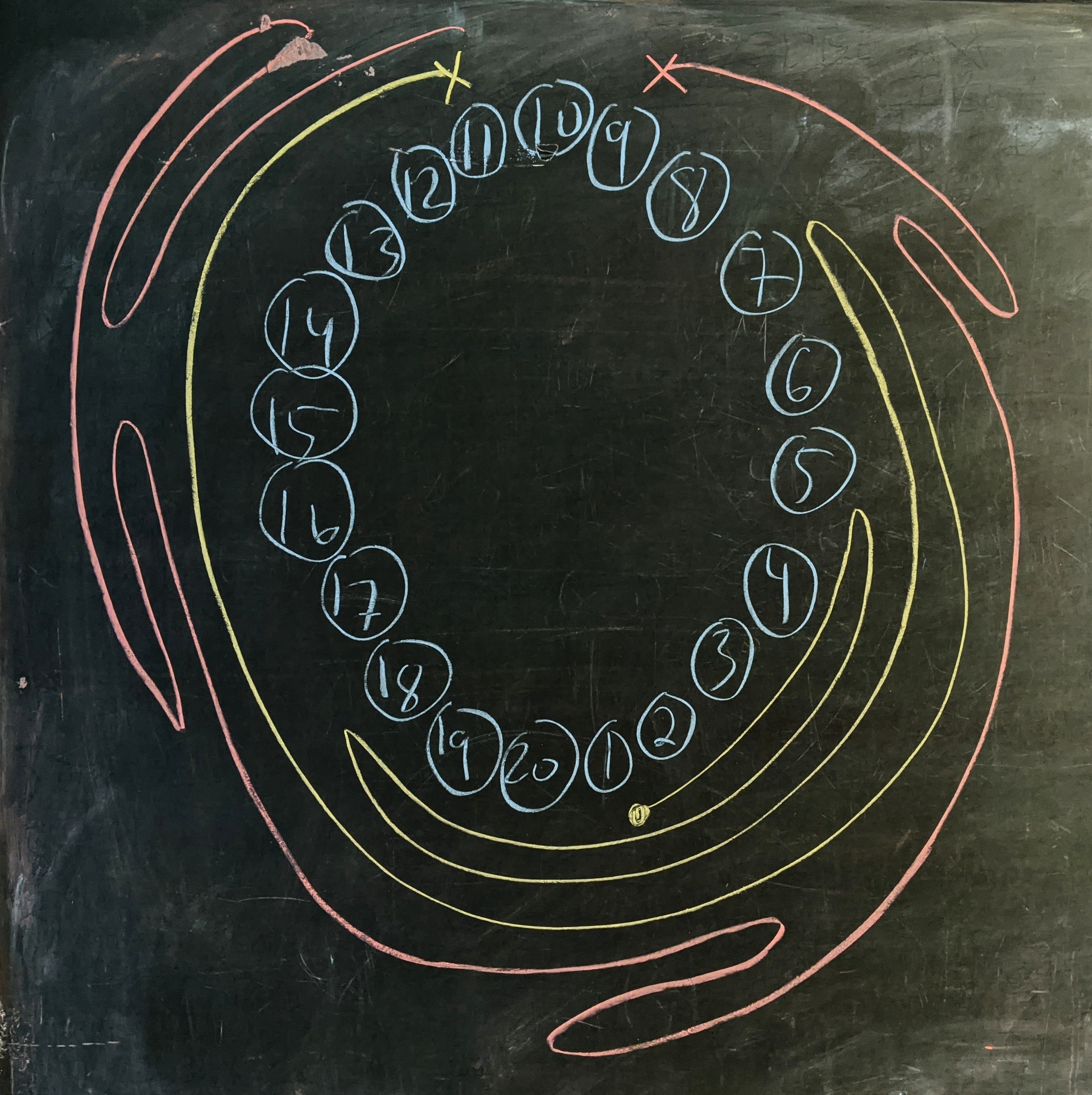

Question: it’s Thanksgiving and your family is gathered ‘round the circular dinner table, Tofurkey in the middle, as is tradition. When the time comes, your Aunt Riddla brings out her famous cranberry sauce, handing it to you to place on the table. Wherever you place it, the person sitting there will take some sauce and then pass it randomly to one of their neighbors with probability $r$ to the right, and probability $\ell$ to the left.

This placement is no small decision though. You want to punish your naughty Uncle Zach so that he gets the cranberry sauce last! Where should you start the sauce off on its journey if you want Uncle Zach to be the most likely to be the last person to get that famous cranberry sauce?

Solution

The cranberry sauce on the table sweeps out a widening arc of diners who’ve had it, dividing the table into two sections. If the sauce wanders inside the arc, then nobody new gets the sauce, and if it reaches the egde then the arc expands.

By construction, the section of people who have not had the sauce is continous, and winnows from each side until there’s only one person left.

Neighbor to neighbor

For someone to be the last person remaining, the arc of the visited has to broaden til it reaches their neighbors, one after the other.

For instance, if the sauce meandered its way from position $1$ to position $11$ (without hitting position $9$ in the process) before turning around and meandering its way to position $9$ (without hitting position $10$ in the process), then the person at position $10$ would be the last to receive the sauce.

We can call the probability of the first path segment $\require{cancel}\Gamma(1\xrightarrow{\cancel{9}} 11)$ signifying that it goes from $1$ to $11$ without bumping into $9.$ Likewise, the probability of the second half is $\Gamma(11\xrightarrow{\cancel{10}} 9).$

It could also have happened in the reverse order, meandering clockwise to visit $9$ (without hitting $11$) before meandering back to $11$ (without hitting $10$). This has probability $\Gamma(1\xrightarrow{\cancel{11}} 9)\times \Gamma(9\xrightarrow{\cancel{10}} 11).$

The probability for the person at $i$ to be the last one visited is the sum of the probability of these two events:

\[\require{cancel} L(10) = \Gamma(1\xrightarrow{\cancel{11}} 9)\cdot \Gamma(9\xleftarrow{\cancel{10}} 11) + \Gamma(1\xleftarrow{\cancel{9}} 11)\cdot \Gamma(11\xrightarrow{\cancel{10}} 9).\]Unrolling the table

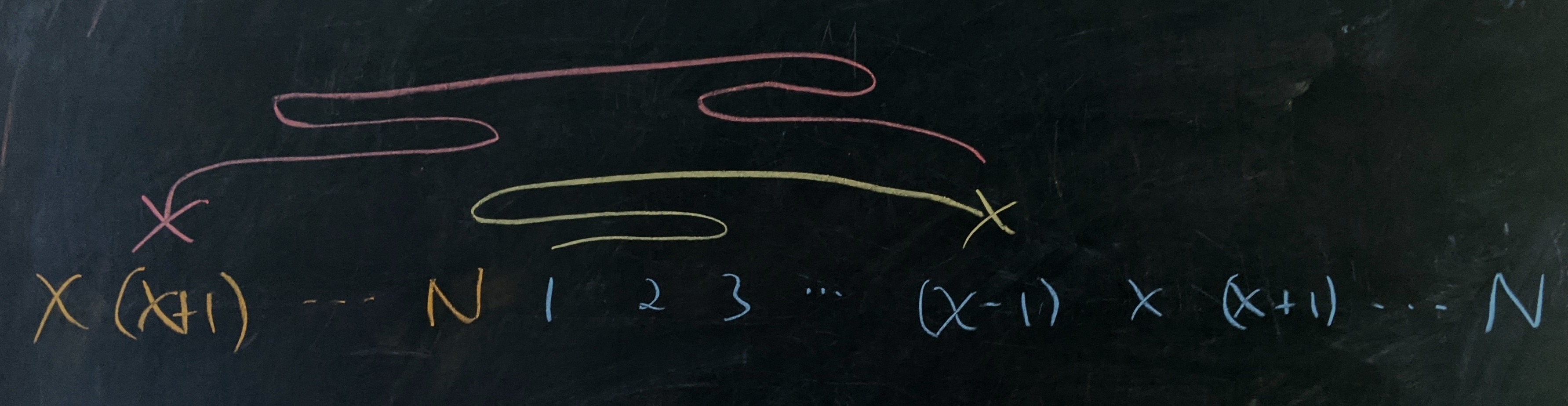

It’s easier to think about this problem if we “unroll” the circle. There are $N$ positions in total and we unroll them so that we have a line going from position $1$ to $N.$ Since almost all trajectories will cross between $1$ and $N,$ we add a redundant copy of positions $x$ to $N$ to the left of $1$:

All possible trajectories we’re interested in will take place along this line.

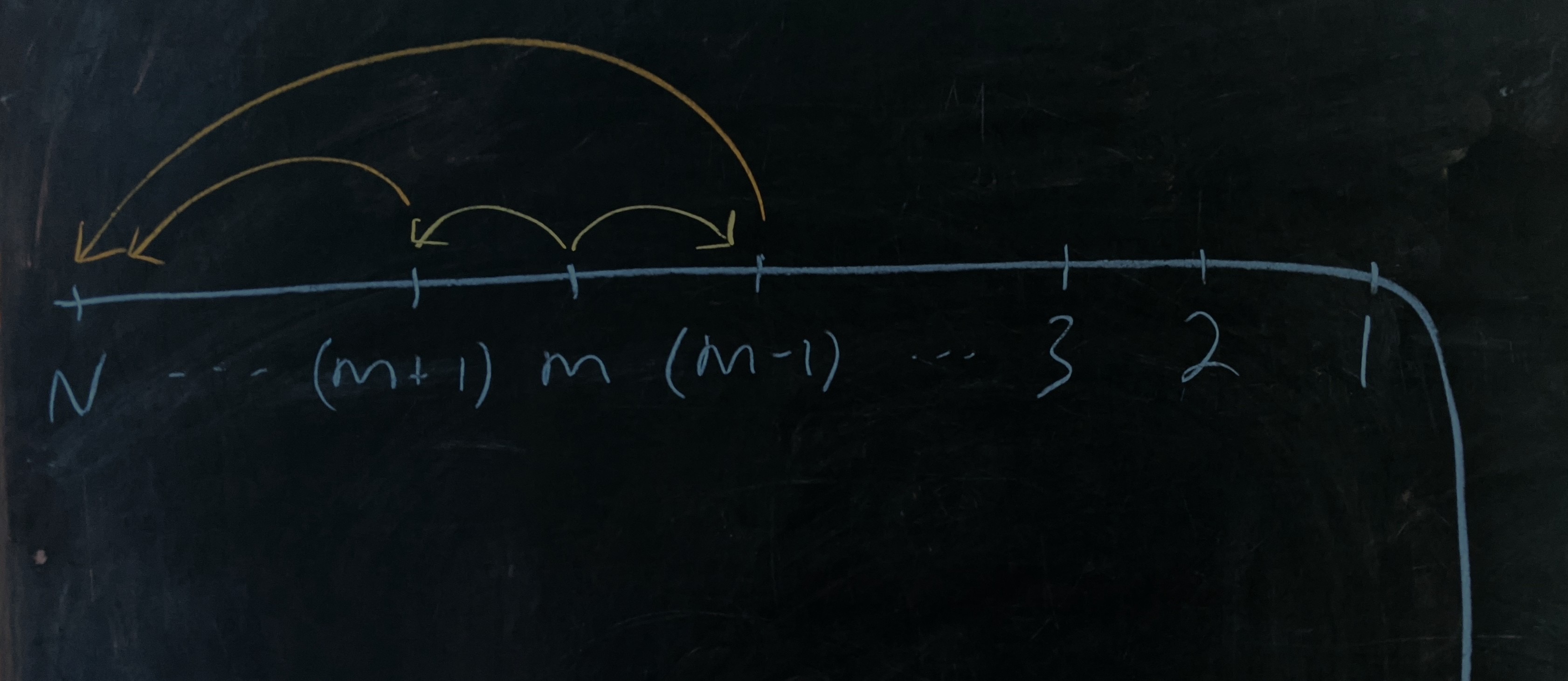

Cliff dancing

Each factor $\require{cancel}\Gamma(i\xrightarrow{\cancel{k}} j)$ is the total probability that, starting from position $i$, a cliff dancer ends up at position $j$ without ever touching position $k.$ Each term has its own start and terminus as well as its own position to avoid, but the problem is generic.

Essentially, the dancer starts out some number of steps from a cliff, and we want to know how likely they are to make it another $\lvert j-i\rvert)$ steps away from the cliff. If they step off the cliff at any point then the path doesn’t count.

As we said above, the original problem breaks into four cases of this cliff problem. If we solve it then the original problem is just a calculation. Let’s call $P_N(m)$ is the probability that the dancer make it to $N$ steps from the cliff given that we start out $m$ steps from the cliff.

By definition, $P_N(0)=0$ as it means we start in freefall from the cliff, and $P_N(N)=1$ since it means the dancer is at position $N$ already. With these boundary values, we can solve the problem by finding a recurrence relationship connecting the survival probability from adjacent positions.

The probability that the dancer survives to step $N$ from step $m$ is the probability that they take a step away from the cliff (probability $\gamma_\text{f}$) and survive from step $(m+1)$, plus the probability that they take a step toward the cliff (probability $\gamma_\text{b}$) and survive from step $(m-1)$:

\[P_N(m) = P_N(m-1)\cdot\gamma_\text{b} + P_N(m+1)\cdot\gamma_\text{f}.\]The two transition probabilities add to $1$ so we can turn this into a relationship between consecutive differences:

\[\left(\gamma_\text{f} + \gamma_\text{b}\right)\cdot P_N(m) = \gamma_\text{b}\cdot P_N(m-1) + \gamma_\text{f}\cdot P_N(m+1),\]and, so

\[\begin{align} \gamma_\text{f}\cdot P_N(m+1) - \gamma_\text{f}\cdot P_N(m) &= \gamma_\text{b}\cdot P_N(m) - \gamma_\text{b}\cdot P_N(m-1) \\ \left(P_N(m+1) - P_N(m)\right) &= \frac{\gamma_\text{b}}{\gamma_\text{f}}\cdot\left(P_N(m) - P_N(m-1)\right). \end{align}\]We can plug this equation back in to itself so that after one step we have

\[\left[P_N(m+1) - P_N(m)\right] = \left(\frac{\gamma_\text{b}}{\gamma_\text{f}}\right)^2\left[P_N(m-1) - P_N(m-2)\right],\]which recurses all the way down to

\[\left[P_N(m+1) - P_N(m)\right] = \left(\frac{\gamma_\text{b}}{\gamma_\text{f}}\right)^m\left[P_N(1) - P_N(0)\right].\]If we add these terms from $m=1$ up to $m=j$ then we get

\[\begin{align} P_N(j+1) - P_N(1) &= P_N(1)\left[\frac{\gamma_\text{b}}{\gamma_\text{f}} + \left(\frac{\gamma_\text{b}}{\gamma_\text{f}}\right)^2 + \ldots + \left(\frac{\gamma_\text{b}}{\gamma_\text{f}}\right)^j\right] \\ P_N(j+1) &= P_N(1) \frac{1 - \left(\frac{\gamma_\text{b}}{\gamma_\text{f}}\right)^{j+1}}{1 - \frac{\gamma_\text{b}}{\gamma_\text{f}}}. \end{align}\]If the dancer gets to step $N$ then they’ve survived and $P_N(N)=1$ so $P_N(1) = (1-\gamma_\text{b}/\gamma_\text{f})/(1 - \left(\gamma_\text{b}/\gamma_\text{f}\right)^N).$

The overall probability of making it to step $N$, starting from step $i,$ without falling off the cliff is

\[P_N(i) = \dfrac{1-\left(\gamma_\text{b}/\gamma_\text{f}\right)^i}{1-\left(\gamma_\text{b}/\gamma_\text{f}\right)^N}.\]Notice that $\gamma_\text{b}$ and $\gamma_\text{f}$ correspond to whatever the transition probabilities are in the backward and forward directions of motion, respectively, so we’ll have to adjust them according to the situation.

Being last

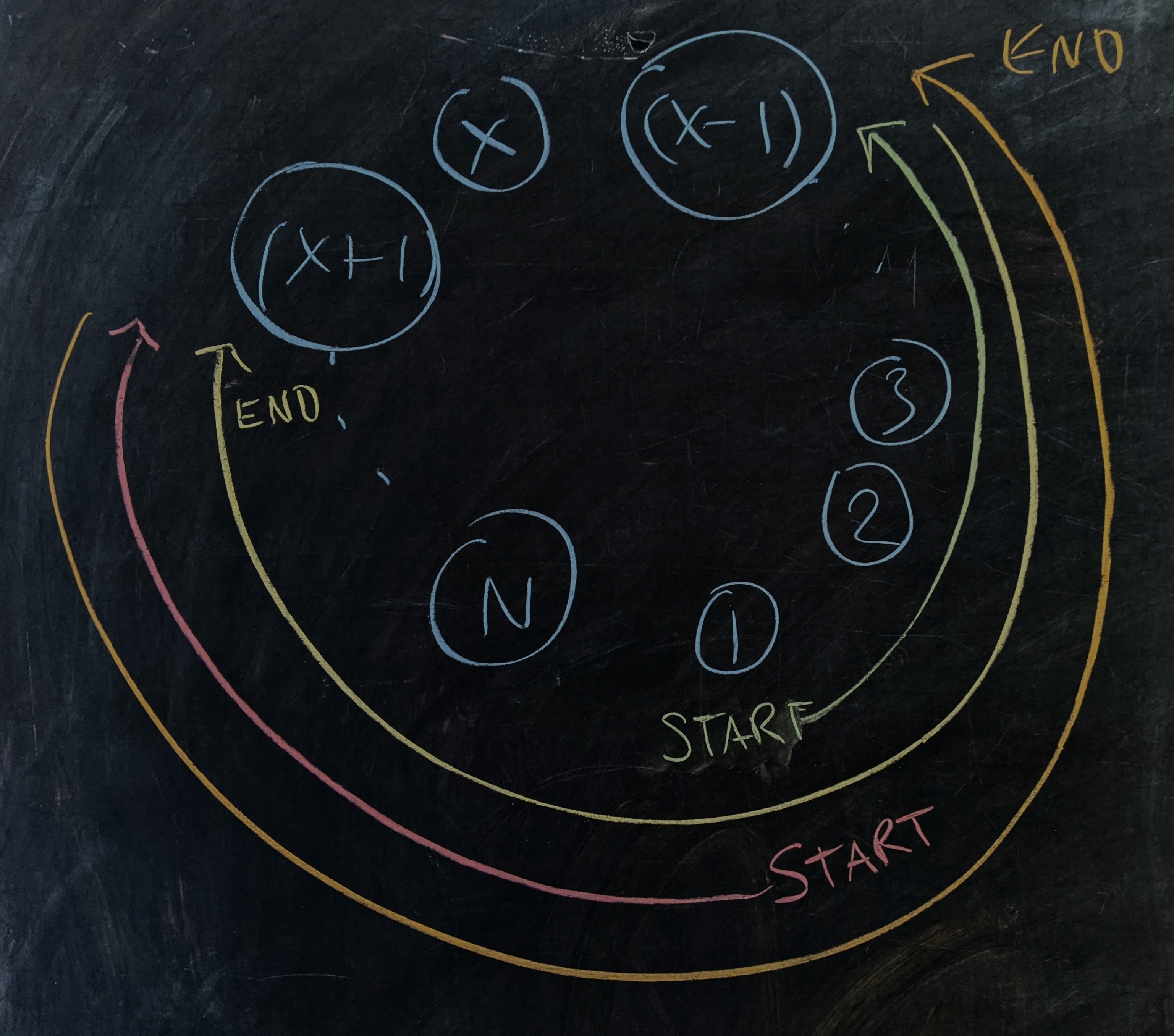

With the cliff problem in hand, we just have to figure out the general form for the paths

Starting from position $1,$ if the sauce moves to $(x-1)$ first then it has to get there without touching $(x+1)$ ($\color{green}{\text{green}}$ path). In effect, the cliff is at position $(x+1),$ which means that $1$ is $N-(x+1)+1 = N-x$ steps from the “cliff.” Also, $(x-i)$ is $(N-2)$ steps from the cliff. This trajectory therefore has probability $P_{(N-2)}(N-x).$ Since this has the sauce moving to the right, $\gamma_\text{f} = r$ and $\gamma_\text{b} = \ell.$

The path from $(x-1)$ to $(x+1)$ ($\color{Yellow}{\text{yellow}}$ path) is $N-1$ steps long and the “cliff” for this segment is located one step away at $x.$ This trajectory therefore has probability $P_{(N-1)}(1).$ Since this has the sauce moving to the left, $\gamma_\text{f} = \ell$ and $\gamma_\text{b} = r.$

If, instead, the sauce first moves to $(x+1),$ it needs to get there without touching $(x-i),$ which places the cliff $(x-2)$ steps from the starting point ($\color{red}{\text{red}}$ path). Also, $(x+1)$ is $(N-2)$ steps from the cliff, so the survival probability is $P_{(N-2)}(x-2).$ Since this has the sauce moving to the left, $\gamma_\text{f} = \ell$ and $\gamma_\text{b} = r.$

The trip back ($\color{orange}{\text{orange}}$ path) is the mirror image of the trip back in the first scenario so the probability is again $P_{(N-1)}(1).$ Since this has the sauce moving to the right, $\gamma_\text{f} = r$ and $\gamma_\text{b} = \ell.$

Putting it all together, we have

\[\begin{align} L(x) &= \overrightarrow{P}_{(N-2)}(N-x)\cdot \overleftarrow{P}_{(N-1)}(1) + \overleftarrow{P}_{(N-2)}(x-2)\cdot \overrightarrow{P}_{(N-1)}(1) \\ &= \frac{1 - (\frac{\ell}{r})^{N-x}}{1-(\frac{\ell}{r})^{N-2}}\cdot \frac{1 - \frac{r}{\ell}}{1-(\frac{r}{\ell})^{N-1}} + \frac{1 - (\frac{r}{\ell})^{x-2}}{1-(\frac{r}{\ell})^{N-2}}\cdot \frac{1 - \frac{\ell}{r}}{1-(\frac{\ell}{r})^{N-1}}, \end{align}\]or, writing $\phi = r/\ell,$ we have:

\[\boxed{L(x) = \frac{1 - \phi^{N-x}}{1-\phi^{N-2}}\cdot \frac{1 - 1/\phi}{1-1/\phi^{N-1}} + \frac{1 - 1/\phi^{x-2}}{1-1/\phi^{N-2}}\cdot \frac{1 - \phi}{1-\phi^{N-1}}}.\]This is a monstrous expression, but with a little bit of algebra, it simplifies nicely:

\[L(x) = \phi^{x-1}\frac{\phi^{-1} - 1}{1 - \phi^{N-1}}.\]Cases and graphs

The fractional term here is constant for a given value of $\phi,$ so the only piece varying is the $\phi^{x-1}$ out front. This means that the ratio of consecutive probabilities, e.g. $L(2)/L(3),$ is equal to $\phi$ so that person $2$ is $\phi$ times as likely to be the last person sauced compared to person $3$, and that person $3$ is $\phi$ times as likely to be last sauced as person $4.$

The first case to check is the one where there’s no imbalance and the sauce has equal chance to go left or right. In this case $\phi=1.$ based on the simple analysis above, $L(x)$ will be a constant function over the $(N-1)$ diners: $L(x) = 1/(N-1).$

If we care to be careful, we can use L’Hôpital’s rule to evaluate the limit as $\phi$ approaches $1:$

\[\begin{align} \lim_{\phi \rightarrow 1} \frac{\phi^{-1} - 1}{1 - \phi^{N-1}} &= \frac{\frac{d}{d\phi}\rvert_{\phi=1}(\phi^{-1} - 1)}{\frac{d}{d\phi}\rvert_{\phi=1}(1 - \phi^{N-1})} \\ &= \frac{-1}{-(N-1)} \\ &= \frac{1}{N-1}. \end{align}\]No matter how we cut it, every person on the circle becomes equally likely to be last to get that famous sauce. For better or worse, there’s no way to target Uncle Zach when $\ell = r.$

As we noticed above, the probability distribution of the last person to get sauced will always be a geometric progression that (when $\phi < 1$) decays like $\phi^{x-1}$ with its overall scale set by $(\phi^{-1} - 1)/(\phi^{N-1} - 1).$

The scale factor is essentially insensitive to $N$ once there are more than $4$ people. For more and more people, we access small tail probabilities, but leave the rightward positions near $1$ almost unchanged. So, when the walk is right-biased $\phi < 1,$ the probability is exponentially suppressed as we go counterclockwise around the circle.

If we want Uncle Zach to be last to get that famous sauce, our best bet is to put him to the left of where the sauce begins its voyage.

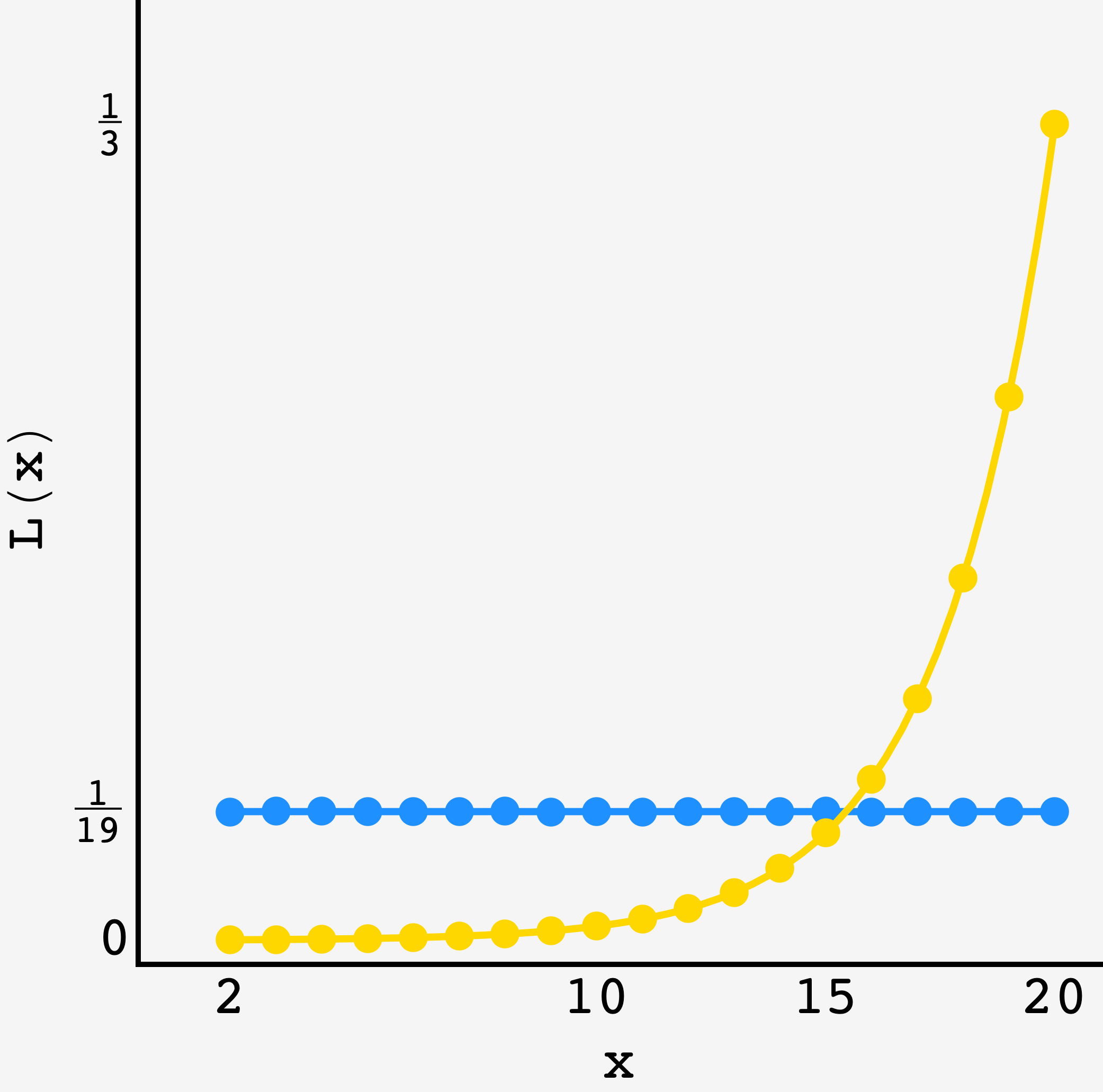

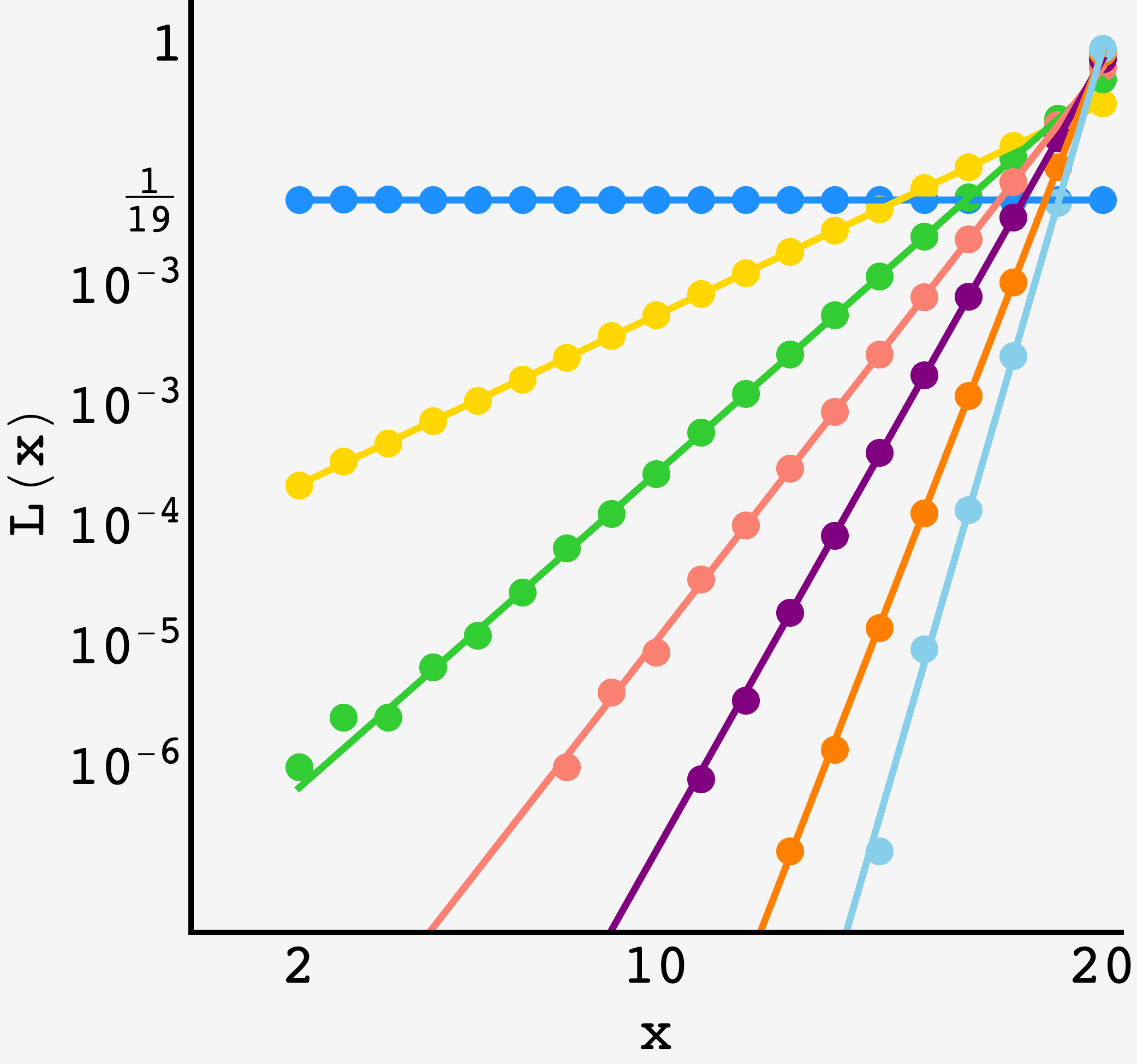

Below is a graph comparing $5\times 10^6$-run simulations of the system for various values of $\phi$ for the $N=20$ person table along with the analytical prediction.

$5\times 10^6$ round simulation of the $N=20$ person table for $\color{blue}{\ell = r}$ and $\color{Goldenrod}{r = 0.6}$ along with the analytical predictions (solid lines).

$5\times 10^6$ round simulation of the $N=20$ person table for $\color{blue}{\ell = r},$ $\color{Goldenrod}{r = 0.6},$ $\color{LimeGreen}{r = 0.68},$ $\color{Salmon}{r = 0.75} ,$ $\color{Purple}{r = 0.82} ,$ $\color{orange}{r = 0.90} ,$ and $\color{SkyBlue}{r = 0.95}$ (logarithmic vertical axis) along with the analytical predictions (solid lines).

Pretty good.

A time to be alone (in preparation)

Of course, just because everyone is equally likely to get the sauce last when $\phi=1$ doesn’t mean that they’ll all wait the same amount of time to get it when they do. We can extend our analysis from above to find the expected amount of time the person who gets the sauce last will wait when they do get it last.

…