Question: A gaggle of graduates gathers round a gargoyle who genuflects until they gear up in a circle upon which they (the gargoyle) announce, I thought no two of you were now in the same position relative to one another but alas I am mistaken, you comprise a number larger than $100$ such that you are the least populous class size for which it is simply not possible for less than $2$ of you to have remained in the correct relative position. How many students are in this graduation class?

Solution

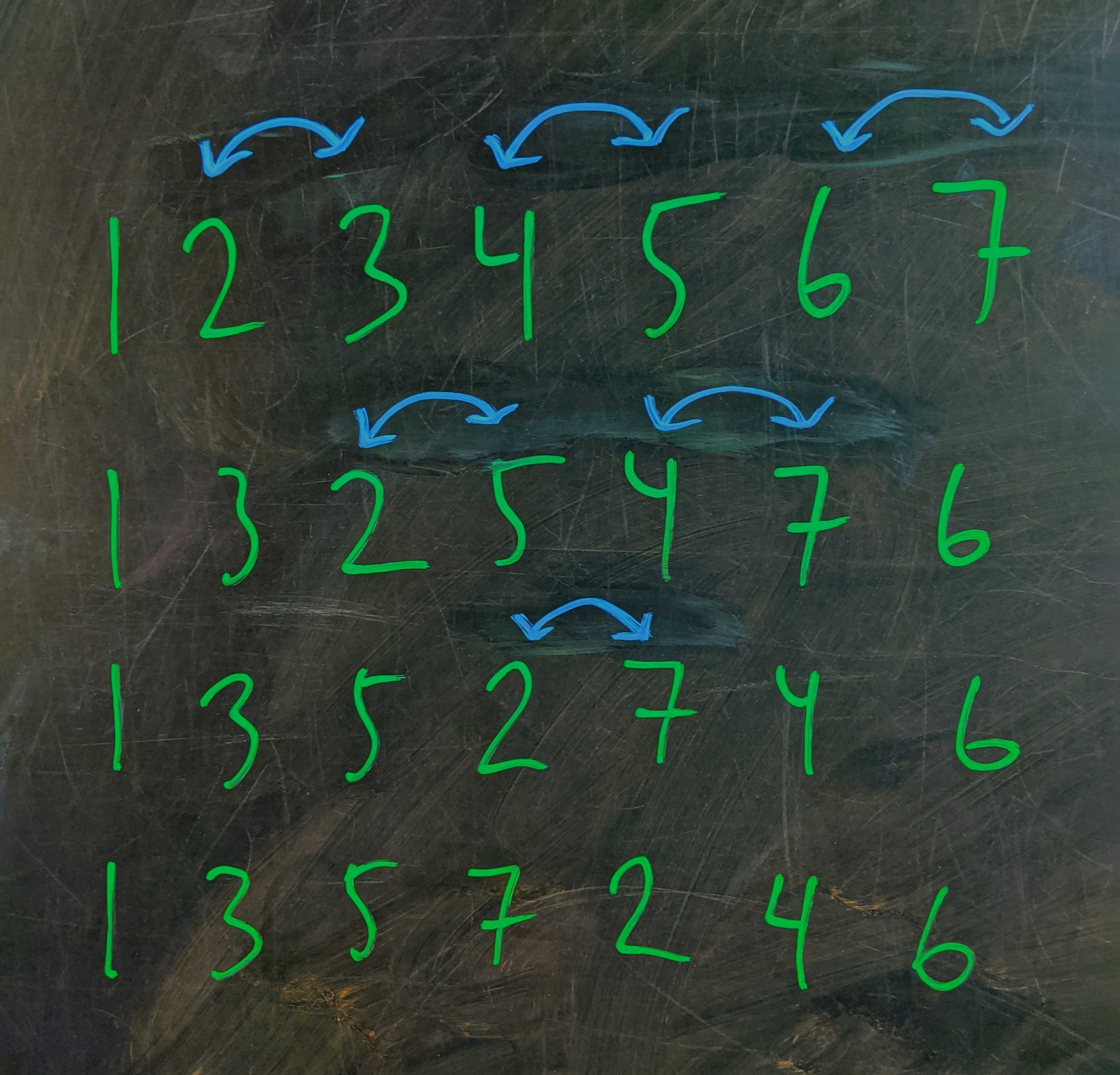

The first useful thing I did was find a construction for arrangements of odd numbers of students where no two students remain in the same relative position after rearranging.

Construction for odd number of students

Since any exchange of positions is rotationally symmetric, we can trivially keep one student in their original spot. Hold them in their spot and swap every subsequent even/odd student pair. That will put the odd register ahead of the even register, breaking all their relative orders, but preserving all the relative orders within the even and odd registers.

From there, I remove the middle swap and move the remaining swaps toward the middle, breaking up the edges of the odd and even registers. Ratcheting the swaps like this eats the even and odd registers from the outside in, eventually moving all the odd-numbered students to the front of the line (in order) and all the even-numbered students to the back (in order). This manifestly destroys all the original orderings.

Is even possible?

For a while, all I had beyond that was the apparent difficulty of constructing a case for any even number of students whatsoever. It seemed impossible, even.

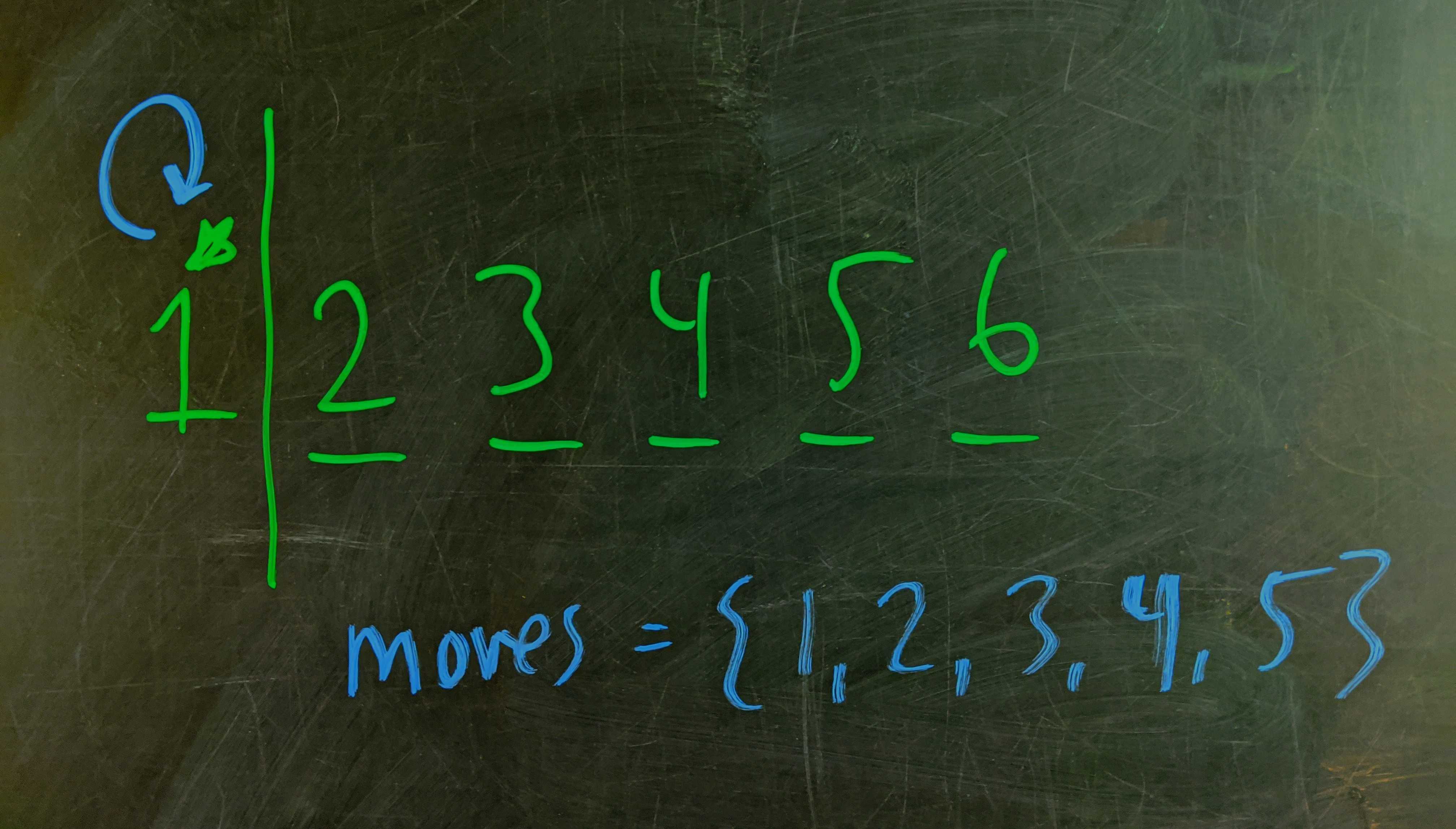

But the fact that the first student can trivially be kept in place got me thinking about the trajectories of the other students.

If all the students are in new spots relative to each other — after they move — then they should all be distinct distances from their original spot. In other words, their new position minus their old position should be distinct for all of them.

Let’s say we have an even number of students, $6$ for argument’s sake, the first student is going to trivially remain in the “same place”.

The others need to move $1$, $2$, $3$, $4$, or $5$ places from where they currently are (since the first student already used the $\text{“0”}$-move. Student $6$ can’t move $1$ spot (or they’d overlap with Student $1$), Student $5$ can’t move $2$ spots, etc. In other words, those last $5$ students have to map among themselves.

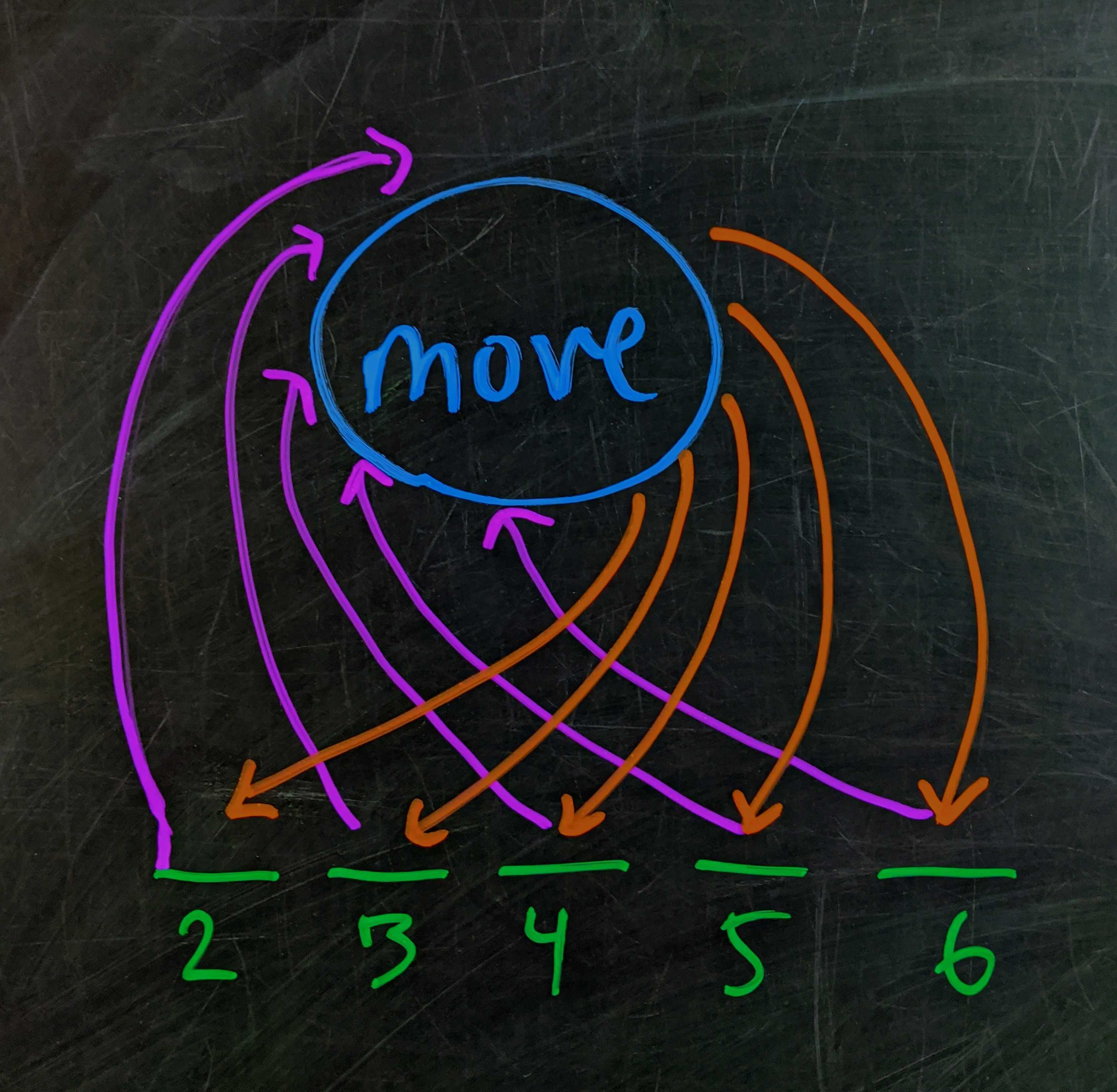

For that to be true, the sum of the new positions has to equal the sum of the original positions:

\[\overbrace{(2+3+4+5+6) + (1+2+3+4+5)}^\text{new positions} = \overbrace{(2+3+4+5+6)}^\text{old positions} \bmod 6.\]The sum $\left(2+3+4+5+6\right)$ disappears from both sides. The other sum $\left(1+2+3+4+5\right)$ has an odd number of odd number which is odd $\bmod 6$, which means the equation is false.

That means there can’t exist a rearrangement of the $5$ students that maps onto their original positions while moving them all distinct distances from their starting positions.

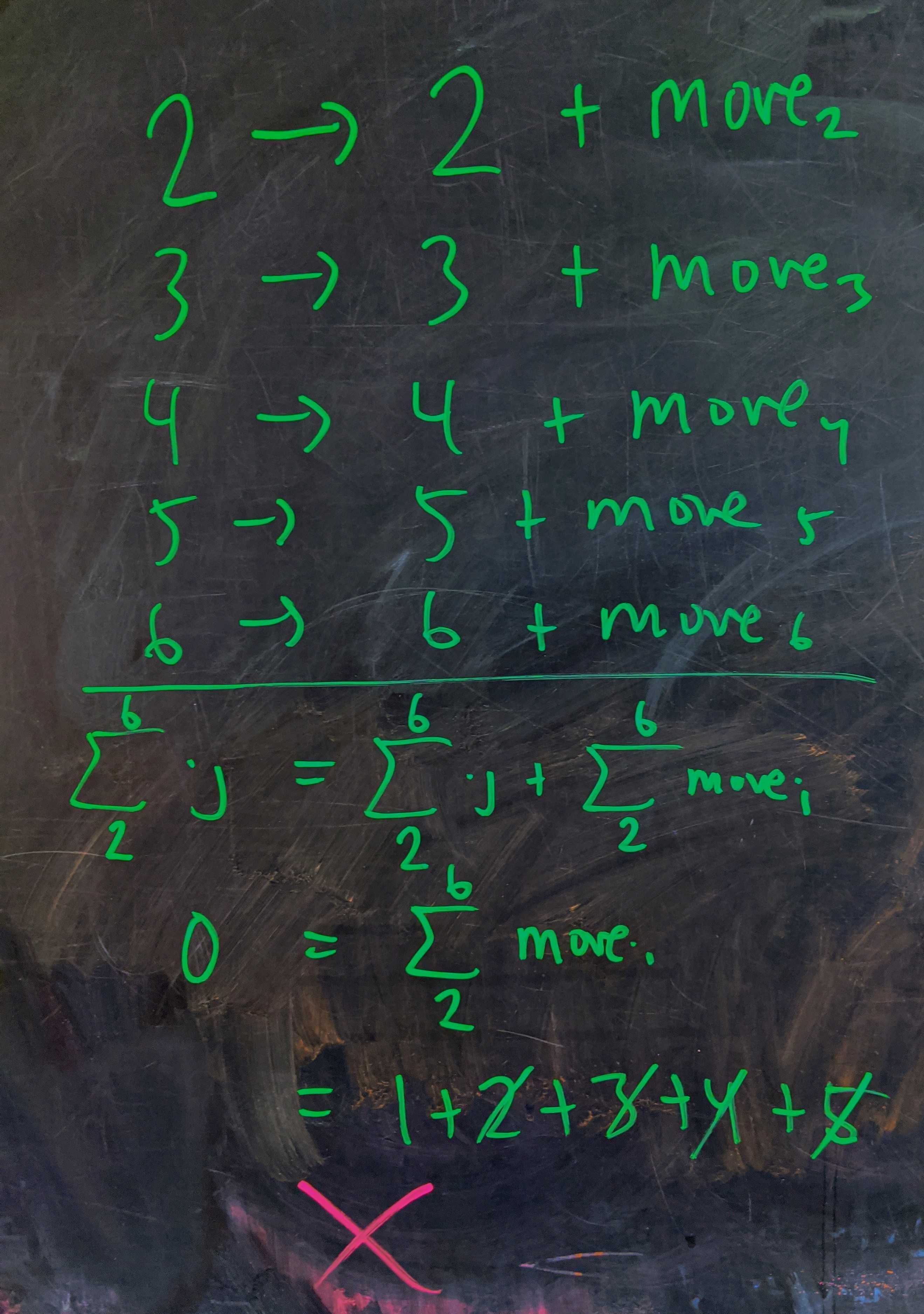

Generalizing, we get

\[\begin{align} 0 &= \text{move}_2 + \text{move}_3 + \ldots + \text{move}_n \\ &=1 + 2 + \ldots + \overbrace{\left(n-1\right)}^\text{odd} \bmod n \\ &= \frac{n(n-1)}{2} \bmod n \end{align}\]which isn’t true when $n$ is even.

So, the smallest $n$ can be is the first even number over $100$, or $102.$