Question: While passing the time at home one evening, you decide to set up a marble race course. No Teflon is spared, resulting in a track that is effectively frictionless.

The start and end of the track are $1$ meter apart, and both positions are $10$ centimeters off the floor. It’s up to you to design a speedy track. But the track must always be at floor level or higher — please don’t dig a tunnel through your floorboards.

What’s the fastest track you can design, and how long will it take the marble to complete the course?

Solution

We want to find the trajectory that makes the time from start to finish as small as possible.

Intuition

The plan is to express the total time $T$ in terms of the shape and endpoints of the trajectory, then use functional calculus to minimize $T$ in terms of the shape.

Without the floor restriction, the problem is analytic and the shortest path is a cycloid.

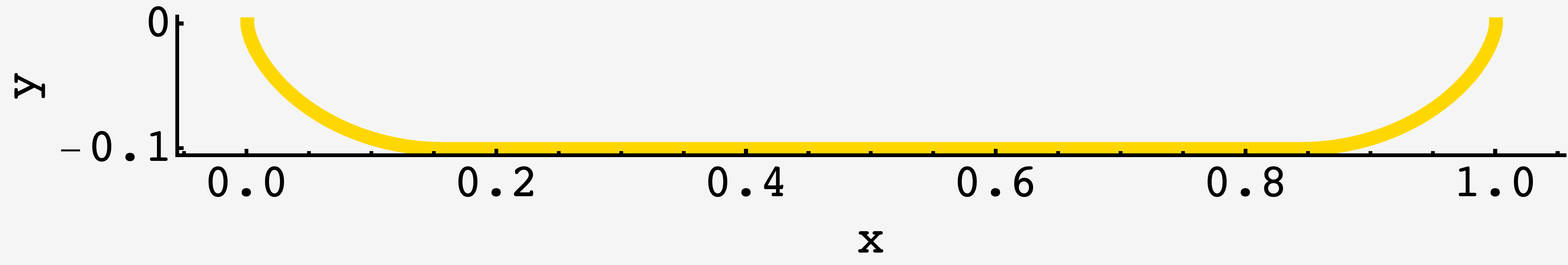

We aren’t allowed to build the track below $\Delta h.$ Still, the unrestricted cycloid is the fastest trajectory between two points. The fastest trajectory is to follow a cycloid down to the lowest allowable height, hit the floor at $\Delta x = h\pi/2,$ follow the floor for a while, then follow the same curve back up to the opposite side.

This makes good physical sense – energy is conserved, and dipping down the full $\Delta y = h$ means that we achieve the maximum velocity for the majority of the trajectory.

With that, what remains is to derive the shape of the curve (a cycloid), use it to determine the value of $\Delta x,$ and plug the trajectory back into the expression for $T.$

Physics

Throughout the process, the total energy is conserved. That means that the sum of potential and kinetic energy doesn’t change. If we pick the ground level as the point of reference (with positive $h$ corresponding to the distance below the ground), and the marble starts at rest, then we have $E_\text{total} = 0$ and so

\[\begin{align} 0 &= T + V \\ &= \frac12mv^2 - mgh, \end{align}\]and $v = \sqrt{2gh}.$

What time is the shape?

The total time $T$ is the sum of all the little time intervals that make up the trajectory:

\[T = \int dt.\]The tiny distance traveled by the marble along the trajectory in time $dt$ is equal to the corresponding tiny distance $ds$ divided by the instaneous velocity:

\[dt = \frac{ds}{v(y)}.\]Expressing the segment in terms of its horizontal and vertical components, we get $ds = \sqrt{dx^2 + dy^2}$ and so

\[\begin{align} T &= \int \dfrac{\sqrt{dx^2 + dy^2}}{v(y)} \\ &= \int dx\,\dfrac{\sqrt{1 + \left(\frac{dy}{dx}\right)^2} }{v(y)}\\ &= \int dx\,\sqrt{\dfrac{1 + {y^\prime}^2}{2gy}} \\ &= \int dx\, \mathcal{T}(y,y^\prime). \end{align}\]At this point, we can identify $\mathcal{T}(y(x),y^\prime(x)),$ the contribution to the total time along the trajectory for each increment in space, $dx.$

Minimization

So, $T(y,y^\prime)$ depends on $y$ and its derivative $y^\prime$ and we want to find the particular curve $y_*(x)$ that minimizes it.

If we had that curve, and it really was a minimum, then any small change we made to the trajectory should keep $T$ very close to the minimum value. In a sense, taking the “derivative” of $T$ with respect to the trajectory $y(x)$ should give us zero.

We can do this by adding an arbitrary, but small amplitude, curve $\varepsilon(x)$ to $y_*(x).$

This means that $y(x) = y_*(x) + \varepsilon(x)$ and $y^\prime(x) = {y_*}^\prime(x) + \frac{d}{dx}\varepsilon(x).$

If we expand around the optimum (this is just a Taylor series) we get

\[\begin{align} T(y_* + \varepsilon(x), y_*^\prime + \tfrac{d}{dx}\varepsilon(x)) &= \int dx\, \mathcal{T}(y_* + \varepsilon(x), y_*^\prime + \tfrac{d}{dx}\varepsilon(x)) \\ &\approx \int dx\, \mathcal{T}(y_*, y_*^\prime) + \int dx\, \left[\dfrac{\partial \mathcal{T}}{\partial y}\varepsilon(x) + \dfrac{\partial \mathcal{T}}{\partial y^\prime}\frac{d}{dx}\varepsilon(x)\right]. \end{align}\]The disturbance $\varepsilon(x)$ is arbitrary, so there isn’t much that we can say about its derivative. However, we can move the derivative off it if we integrate by parts. Doing that, we get

\[\delta T \approx \int dx\, \left[\dfrac{\partial \mathcal{T}}{\partial y} - \frac{d}{dx}\dfrac{\partial \mathcal{T}}{\partial y^\prime}\right]\varepsilon(x).\]For the optimal trajectory, this variation will be equal to zero. Looking at the integral, $\varepsilon(x)$ is, apart from having small magnitude, a totally arbitrary function.

For example, it could be positive wherever the bracketed expression is positive, and negative wherever it’s negative, which would make the integral a positive number. The only way for the variation to be zero, regardless of $\varepsilon(x),$ is for the bracketed expression itself to be everywhere zero.

This means that the optimal trajectory obeys

\[\frac{\partial\mathcal{T}}{\partial y} = \frac{d}{dx}\frac{\partial\mathcal{T}}{\partial y^\prime},\]which is the the Euler-Lagrange equation.

Differential equation

To take these derivatives, we can use the explicit form for $\mathcal{T}$ above, which yields an unholy mess but boils down nicely to

\[\begin{align} 0 &= \dfrac{y^{\prime\prime}}{1+{y^\prime}^2} + \dfrac{1}{2y} \\ &= 2y^{\prime\prime}y + 1 + {y^\prime}^2. \end{align}\]If we can solve this differential equation, then the ideal shape will be revealed.

Reverse engineering

The equation has a mixed $y^{\prime\prime}y$ term, indicating coupling between the linear and first order terms.

The coupled term can’t simply be $y^\prime y$, or else there wouldn’t be a $2.$ But the $2$ could arise if the term were $y{y^\prime}^2.$

Following this thread, if we multiply through by another factor of $y^\prime,$ we get

\[2y^{\prime\prime}y^\prime y + y^\prime + {y^\prime}^3 = 0,\]which is the derivative of

\[y\left(1+{y^\prime}^2\right).\]This leads us to

\[y\left(1+{y^\prime}^2\right) = \text{const.}\]or

\[\frac{dy}{dx} = \sqrt{\frac{\text{const.} - y}{y}}.\]Since we don’t want the marble to bounce, the curve should meet the floor at zero slope. We know that $dy/dx$ is zero when $y=h,$ which tells us that $\text{const.} = h.$

We can actually solve for $y$ without integrating.

Drawing a diagram, we can equate $dy/dx$ with the tangent of the angle with the horizontal (like we did in a recent problem) and solve for $y$ algebraically

This gives the expected limits, with $y=0$ at the beginning $\left(\theta = 0\right)$ and $y=h$ at the end $\left(\theta = \pi/2\right).$

With this in hand, we can find $x$ by

\[\begin{align} \frac{\cos\theta}{\sin\theta} &= \frac{dx}{dy} \\ &= \frac{dx}{d\theta}\frac{d\theta}{dy} \\ &= -\frac{dx}{d\theta}\frac{1}{2h\cos\theta\sin\theta}, \end{align}\]or

\[\frac{dx}{d\theta} = - h\cos^2\theta.\]Playing around with derivatives, $\sin\theta\cos\theta\rightarrow \left(2\cos^2\theta - \theta\right),$ so $h\left(\theta + \sin\theta\cos\theta\right)$ should give the behavior we’re looking for:

\[x = h\left(\theta + \sin\theta\cos\theta\right).\]With these solutions in hand, we can figure out where the marble hits the floor (and likewise, when it starts to curve back up), as well as the total time required for the marble to make its transit.

Characterizing the transit

The marble follows the curve defined by $\left(x(\theta),y(\theta)\right)$ down to the floor, which it reaches when $\theta = \pi/2,$ giving $x_h = \tfrac12h\pi.$

From there it slides the distance $(1-2x_h)$ before following the same curve back up at $x=1-x_h.$.

Timing the transit

When the marble reaches the floor, its velocity is $\sqrt{2gh},$ so it spends

\[T_\text{flat} = \dfrac{w-2x_h}{\sqrt{2gh}}\]rolling on the floor. But how much time does it spend on the curve?

To find out, we can go back to our original integral, now with the benefit of $y(\theta):$

\[\begin{align} T_\text{curve} &= \frac{1}{\sqrt{2g}}\int\limits_0^{x_h}dx\, \sqrt{\dfrac{1+{y^\prime}^2}{y}} \\ &= \frac{1}{\sqrt{2g}}\int\limits_0^{\tfrac12\pi}\frac{dx}{d\theta}d\theta\, \sqrt{\dfrac{1+\frac{h-y}{y}}{y}} \\ &= \frac{1}{\sqrt{2g}}\int\limits_0^{\tfrac12\pi}d\theta\, \sqrt{\dfrac{h}{y^2}}h\left(1-\sin^2\theta+\cos^2\theta\right) \\ &= \sqrt{\frac{h}{2g}}\int\limits_0^{\tfrac12\pi}d\theta\, \dfrac{1}{\cos^2\theta}h\left(2\cos^2\theta\right) \\ &= \sqrt{\frac{h}{2g}}\pi \end{align}\]Despite all the explosions and loud noises, the total time taken reduces to nothing but

\[\begin{align} T_\text{total} &= 2T_\text{curve} + T_\text{floor} \\ &= \sqrt{\frac{2h}{g}}\pi + \frac{w-2x_h}{\sqrt{2gh}} \\ &= \frac{h\pi + w}{\sqrt{2gh}}. \end{align}\]Taking limits, this has the behavior we expect. When $w\gg h,$ we get $T_\text{total} \approx w/\sqrt{2gh},$ the back of the envelope solution.

Were there no floor, we could have set the initial condition through $x(\tfrac12\pi) = \tfrac12 w,$ giving $x = \tfrac{w}{\pi}\left(\theta + \sin\theta\cos\theta\right)$ and $y = \frac{w}{\pi}\cos^2\theta.$ As it happens, this is the relationship between $h$ and $w$ we get minimizing the expression above.