Question: One cloudless night, the sky above you contains an equal number of visible stars and planes. Suddenly, you spot a point of light at a particular angle of elevation above the horizon. Based purely on this angle, you want to determine whether the point of light is more likely to be a star or a plane.

While figuring this out, you make the following simplifying assumptions:

- Earth is a perfect sphere with a radius of 4,000 miles.

- Stars are equally likely to be anywhere in the night sky.

- Planes are equally likely to be flying anywhere over Earth (i.e., not just limited to established air routes) at an altitude of 6 miles. You can neglect takeoffs and landings.

After some quick thinking, you realize that at this particular angle, the point of light is equally likely to be a star or a plane. What is this angle of elevation?

Solution

On first thought, there doesn’t seem to be a puzzle — the planes are spherically symmetric and so are the stars. What makes the difference?

The stars are spherically symmetric, in actuality and with respect to our perspective. The planes however are on a nearby sphere which means that, for the same angular increment, there are more planes at the horizon than there are when we look straight up.

To see this, we can draw a sphere representing the uniform plane distribution. A patch of view, perpendicular to our line of sight, sweeps out a larger patch on the plane sphere at the horizon, whereas at zenith, they are one and the same.

Calculation

With this intuition, we can go about calculating the probability distributions.

Stars

If we gaze up from the horizon, stars are equally likely to be in any angular patch. Since the stars are equally likely to be anywhere in our gaze, and our gaze covers the solid angle $2\pi,$ the probability distribution is

\[p_\text{stars}(\theta) = \frac{1}{2\pi}.\]Once we have $p_\text{planes}(\theta),$ we’ll check to see at what value of $\theta$ it overtakes $p_\text{stars}(\theta).$

Airplanes

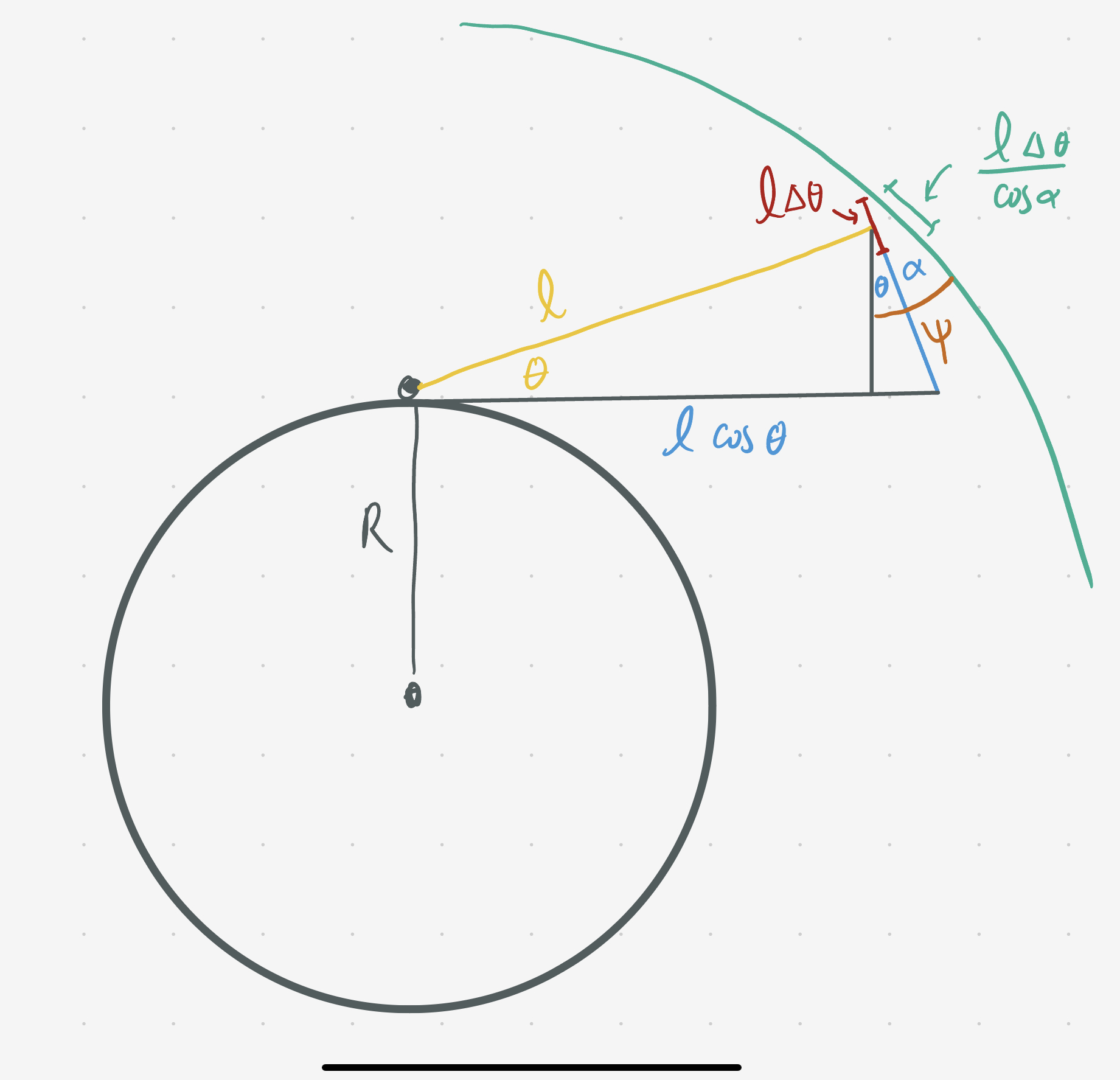

With the airplanes, we have to account for the tilt of the surface of the airplane sphere relative to our line of sight, and the changing distance to the airplane sphere, $\ell(\theta).$

The probability of seeing an airplane in a vision patch is proportional to its area. Let’s take some small angular extents $d \theta$ and $d \phi$ to define our patch.

Looking at an angle $\theta$ from the horizon, the extent in the $\theta$ direction is given by $\ell(\theta)d\theta$ while the extent in the $\phi$ direction is $\ell(\theta)\cos\theta d\phi,$ making the area of the patch

\[dA = \left[l^2(\theta)\cos\theta\right] d\theta\, d\phi.\]If the airplane sphere were always parallel to our vision patch, this would be it. However, away from the zenith, the tilt increases with $\theta.$

The surface of the sphere makes angle $\psi$ with the vertical. As shown in the diagram, the tangent of this angle is

\[\tan\psi = \dfrac{dx}{dy}.\]The surface of the sphere is defined by $y^2 = (R+h)^2 - x^2$ which gives $dx/dy = -y/x$ (sign not important).

Drawing the right triangle defined by $\ell(\theta)$ and extending a similar right triangle off the back, we can see that the angle between the airplane sphere and our vision patch is $\alpha = \psi - \theta = \arctan\frac{y}{x} - \theta.$

We can express $x$ and $y$ in terms of $\theta$ through $x = \ell(\theta)\cos\theta$ and $y = R + \ell(\theta)\sin\theta.$

With all this taken into account, the effective area on the surface of the plane sphere occupied by a patch of vision at angle $\theta$ to the horizon is

\[\begin{align} dA^\prime &= \dfrac{dA}{\cos\alpha(\theta)} \\ &= \left[\dfrac{\ell^2(\theta)\cos\theta}{\cos\alpha(\theta)}\right] d\theta\, d\phi. \end{align}\]Now $\ell$ is itself a function of $\theta,$ which we can find with the law of cosines, which for posterity, we can derive.

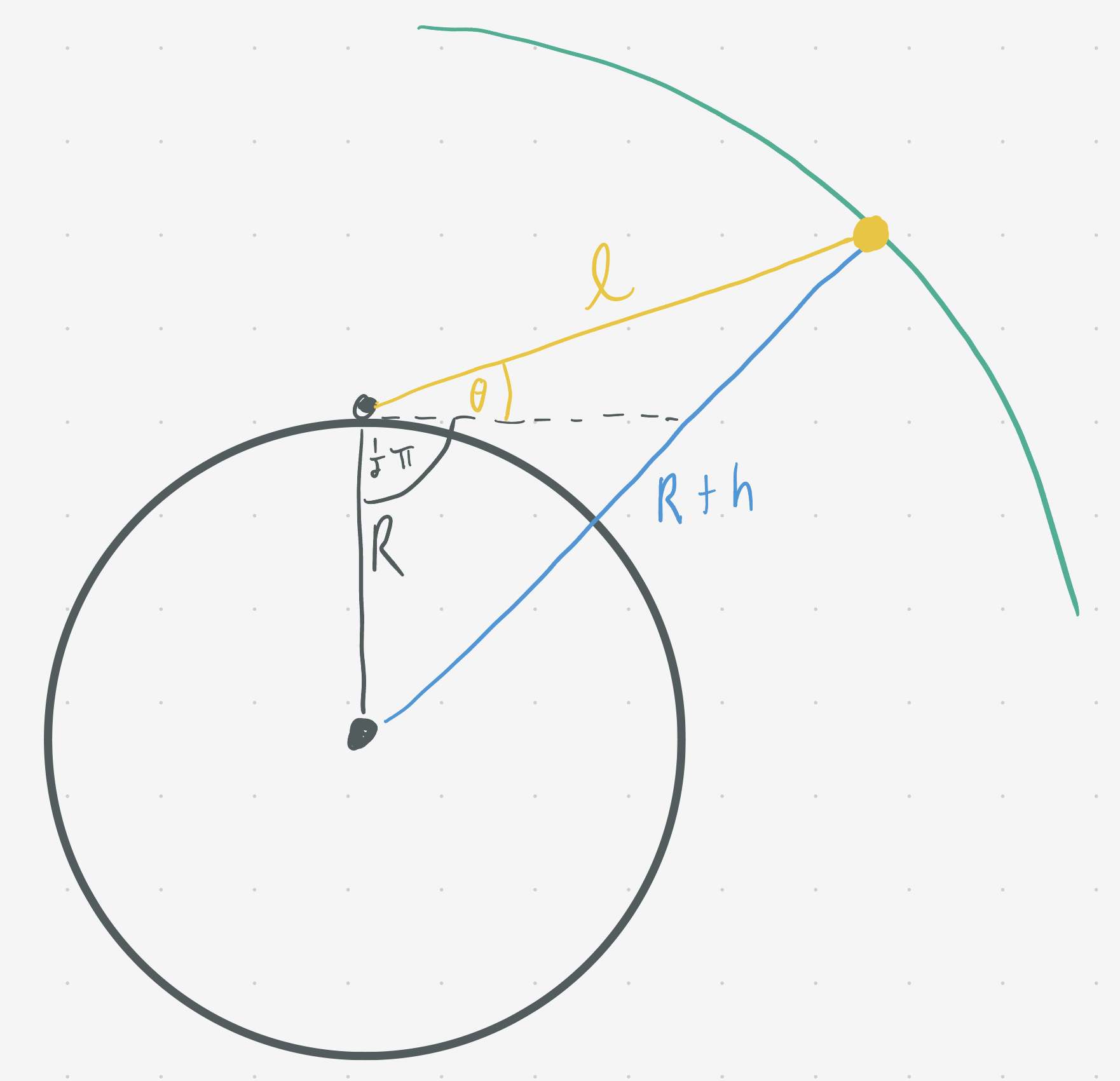

Taking the sides to be vectors of lengths $R,$ $R+h,$ and $\ell,$ we have

\[\begin{align} \lvert\vec{R}+\vec{h}\rvert^2 &= \left(\vec{\ell} + \vec{R}\right)\cdot\left(\vec{\ell} + \vec{R}\right) \\ &= \ell^2 + R^2 + 2\ell R\cos\left(\tfrac12\pi - \theta\right) \end{align}\]which, after solving the quadratic for $\ell,$ gets

\[\ell(\theta) = \sqrt{h (h + 2 R) + R^2 \sin^2\theta} - R \sin\theta.\]If the Rube Goldberg machine we’ve constructed is correct, we should be able to integrate this over $\theta$ and $\phi$ to find the surface area of the portion of the airplane sphere we can see. Indeed, integrating $\ell^2 \cos\theta/\cos\alpha$ over $\theta$ and $\phi$ we get $\approx 151023.64\ldots$ which matches the expectation from $2\pi(R+h)h.$

With this in hand, we can find

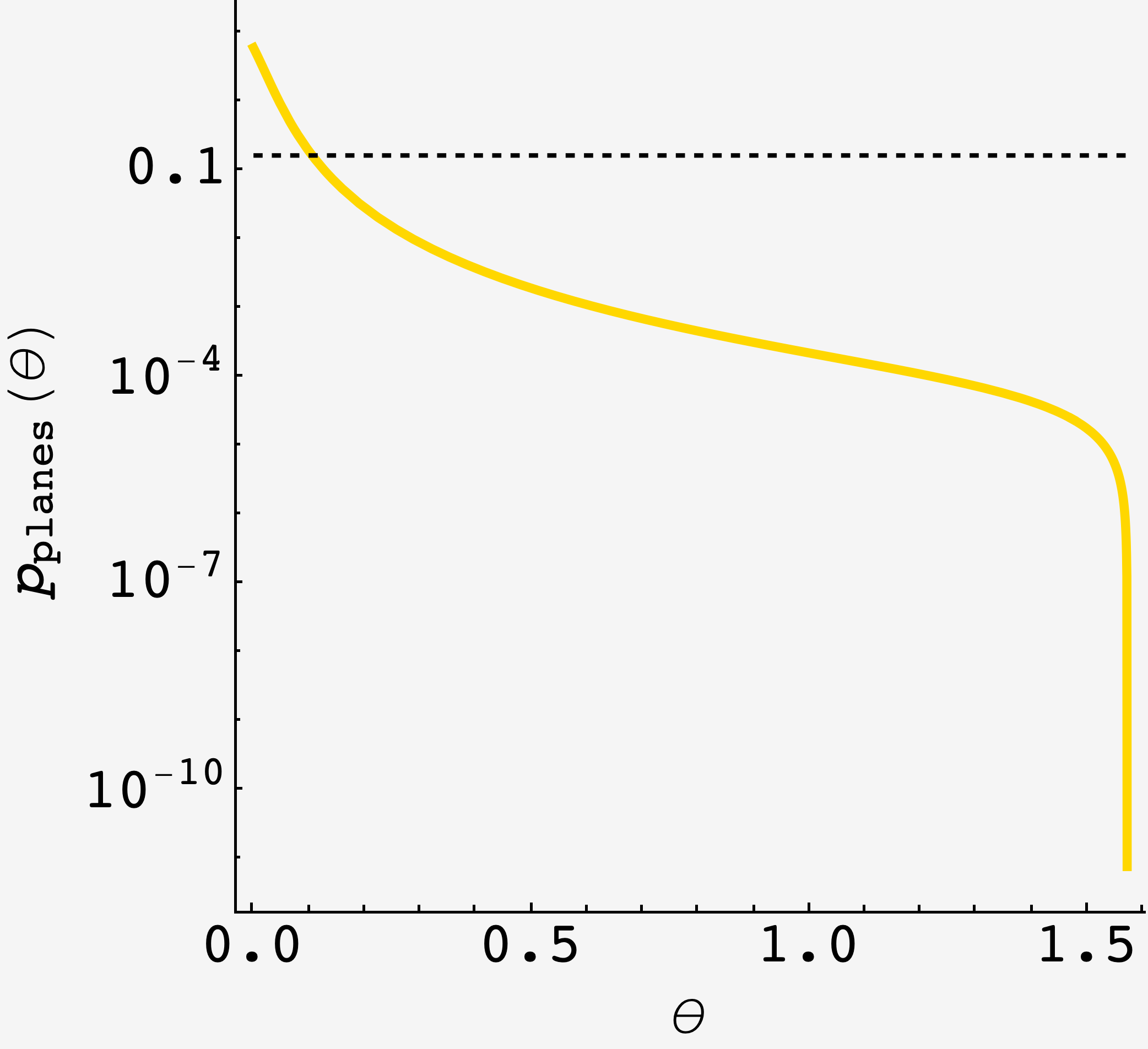

\[p_\text{planes}(\theta) = \dfrac{\dfrac{\ell^2(\theta)\cos\theta}{\cos\alpha(\theta)}}{2\pi\int\limits_0^{\frac12\pi} \dfrac{\ell^2(\theta^\prime)\cos\theta^\prime}{\cos\alpha(\theta^\prime)}\, d\theta^\prime}.\]Now, we can plot $p_\text{planes}(\theta)$ to see where it crosses $1/2\pi.$ The effect of the tilt is to compress a very large amount of airplane sphere into vision patches near the horizon, so we should expect planes to be far more likely at the horizon, then taper off as we approach the zenith. This is just what we see:

Zooming in on the intersection, we find that the likelihood of an airplane matches the likelihood of a star when $\theta \approx 0.10563$ or about $6.05$ degrees above the horizon.