Question: Today I happen to be celebrating the birthday of a family member, which got me wondering about how likely it is for two people in a room to have the same birthday.

Suppose people walk into a room, one at a time. Their birthdays happen to be randomly distributed throughout the $365$ days of the year (and no one was born on a leap day). The moment two people in the room have the same birthday, no more people enter the room and everyone inside celebrates by eating cake, regardless of whether that common birthday happens to be today.

On average, what is the expected number of people in the room when they eat cake?

Extra credit: Suppose everyone eats cake the moment three people in the room have the same birthday. On average, what is this expected number of people?

Solution

I found three ways to solve this problem: by approximation, counting through recursion, and counting through combinatorics.

The first way is the most insightful and helps reveal what the exact solutions add to the picture, so we’ll start there.

Approximate argument

One way to treat the birthday twin case is to multiply the probability that the second person doesn’t collide with the first $(1-1/365),$ with the probability that the third person doesn’t collide with the first two $(1-2/365)$ and so on up to the $n^\text{th}$ person. The resulting expression is exact and at some point falls below $50\%$ giving us the answer to the classic birthday birthday collision problem.

Each term in the product $(1-j/365)$ is approximately equal to $e^{-j/365}$ and so we can add up all the exponents $\frac{1}{365}\left(1 + 2 + \ldots + n\right) = n(n+1)/2$ and we end up with $P(\text{no collisions in }n\text{ people}) \approx e^{-n^2/(2!\cdot 365)}.$ This is nice but, but the logic doesn’t easily extend to triplets and above.

A more audacious way to get the same result is to think about pairs. As long as no pair of people in the room share the same birthday, we keep adding new people. Among $n$ people there are $\binom{n}{2}$ possible pairs and the chance that any given pair has a collision is $\frac{1}{365},$ so the probability of no collisions among $n$ people is approximately

\[\left(1-\tfrac{1}{365}\right)^\tbinom{n}{2} \approx e^{-\tbinom{n}{2}/365} \approx e^{-n^2/(2!\cdot365)}\]The probability of having a collision among $n$ (or fewer) people is then \(\text{cdf}(n) \approx 1 - e^{-n^2/(2!\cdot365)}.\)

The big idea here is that the low probability of getting a collision is up against the number of pairs. As soon as the number of pairs is on the order of the inverse probability, we should expect to see a collision.

To find the average amount of people at which the collision first appears $\langle n\rangle$, we need the distribution ($\text{pdf}$) of $n,$ which we can get the $\text{pdf}$ by differentiating the $\text{cdf}$

\[\text{pdf}(n) = \dfrac{d}{dn}\text{cdf}(n) = \dfrac{n}{365}e^{-n^2/(2!\cdot365)}.\]The expected value of $n$ is then $\int\limits_0^{365+1}\hspace{-0.8em}dn\ n\ \text{pdf}(n),$ or

\[\langle n_2\rangle = \frac{1}{365}\int\limits_0^{365+1}\hspace{-0.8em}dn\ n^2 e^{-n^2/(2!\cdot 365)}\]We can clean this up in a few ways. First of all, the exponential is basically dead by $n=366$ so we can make the upper bound $\infty$ without losing much accuracy. Second, we substitute $\beta = n^2/(2!\cdot 365)$ so that $d\beta = \frac{1}{365}n\ dn.$ With this, the expression becomes

\[\langle n_2\rangle = \sqrt{2\cdot 365} \int\limits_0^\infty d\beta\ \sqrt{\beta}e^{-\beta}\]The integral is just the gamma function of $3/2$ so we get $\langle n_2\rangle = \sqrt{2\cdot365}\cdot\Gamma(3/2) = \sqrt{365\pi/2}$ which is approximately $23.94$

The same logic extends to triplets, quadruplets, and so on. For triplets, $\langle n\rangle$ is

\[\langle n_3\rangle = \int\limits_0^{\infty}dn\ \frac{n^3}{2!\cdot 365^2} e^{-n^3/(3!\cdot 365^2)}\]which, after a simular substitution, becomes

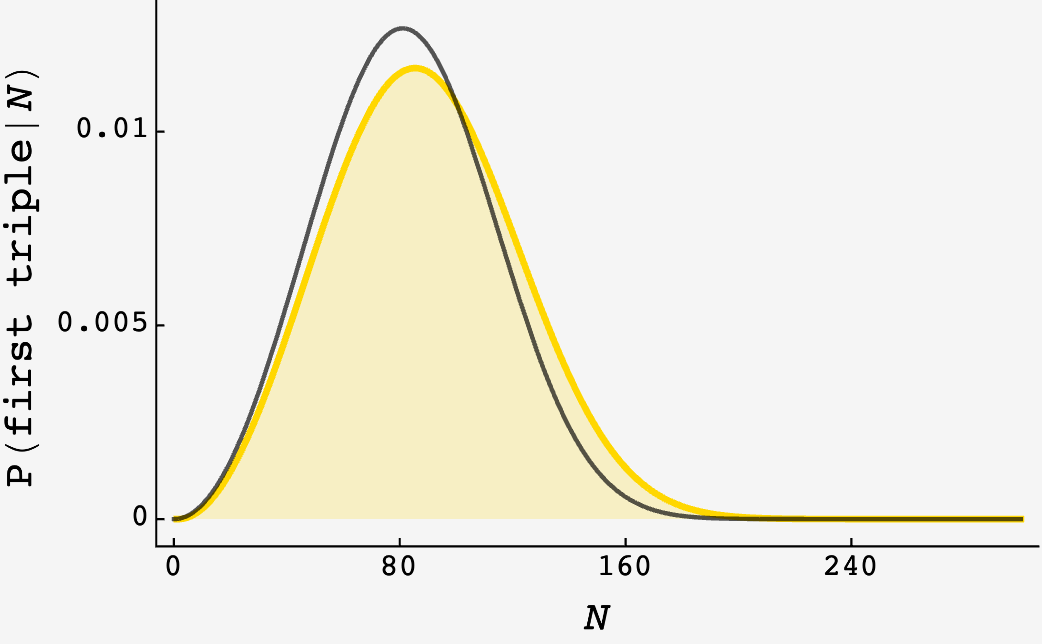

\[\langle n_3\rangle \approx 365^{2/3}\cdot\sqrt[3]{3!}\cdot\Gamma(4/3) \approx 82.87\]In general, the prediction of the approximation for $c$-birthday collisions is $\langle n_c\rangle \approx 365^{(1-1/c)}\cdot\sqrt[c]{c!}\cdot\Gamma(1+1/c).$ However, the assumption used to make the approximation starts to devastate around $6$- or $7$-birthday collisions.

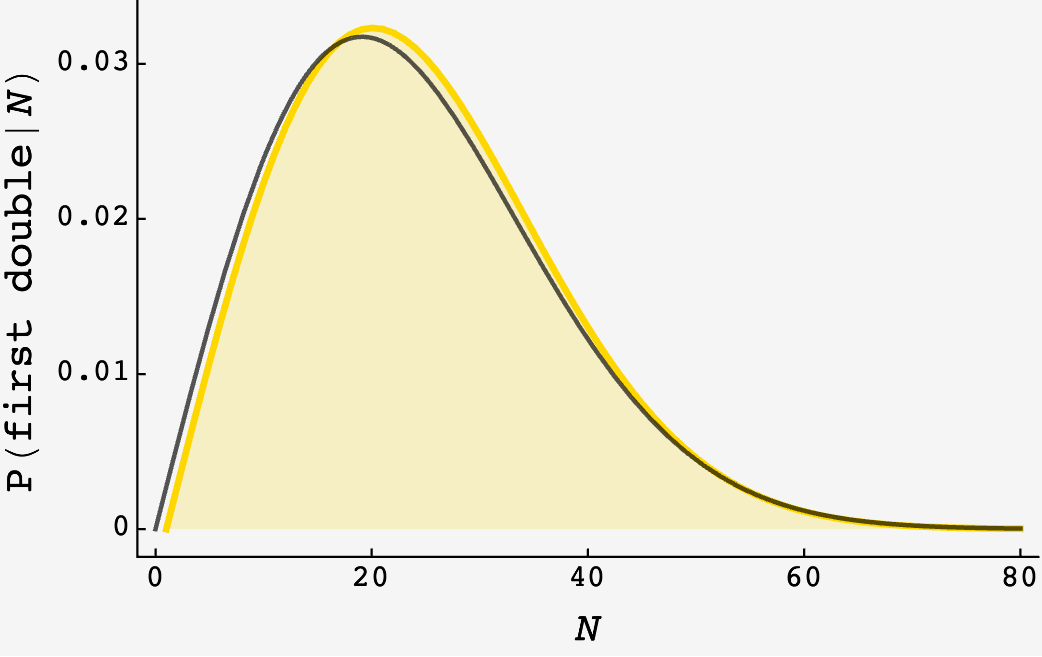

As we’ll see, the true value for birthday twins is about $24.62$ and for birthday triplets it is $88.74,$ so these aren’t perfect, but they aren’t too bad either.

Recursion

We can simplify our thinking about the problem by finding a good way to describe the states. On the way to having doublets, a number has to be a singlet. Likewise, on the way to being a triplet, a number has to be a doublet.

These are the macroscopic states we care about (how many singlets, doublets, and so on, that there are) not the specific numbers that are chosen. So, we can track the probability of states $(s, d).$

Each time we add a number, we can either pick a number that hasn’t been chosen before $(s-1,d)\rightarrow(s,d)$ or pick a number that’s currently a singlet $(s+1,d-1)\rightarrow(s,d).$

The probability of these events are $\tfrac{365-(s-1)-d}{365}$ and $\tfrac{s+1}{365},$ respectively.

The recursion is then (writing $C$ for $\text{cdf}$)

\[C(s,d) = \dfrac{365-(s-1)-d}{365}C(s-1,d) + \dfrac{s+1}{365}C(s+1,d-1)\]With the base conditions of $C(0,0)=1$ and $C(s,d) = 0$ whenever $s$ or $d$ is less than zero.

Implemented, this looks like

C[0, 0] = 1;

C[s_, -1] := 0;

C[-1, d_] := 0;

C[s_, d_] :=

C[s, d] =

(365 - (s - 1) - d)/365 C[s - 1, d] + (s + 1)/365 C[s + 1, d - 1];

As a sanity check, we can look at $C(s,0)$ as $s$ varies.

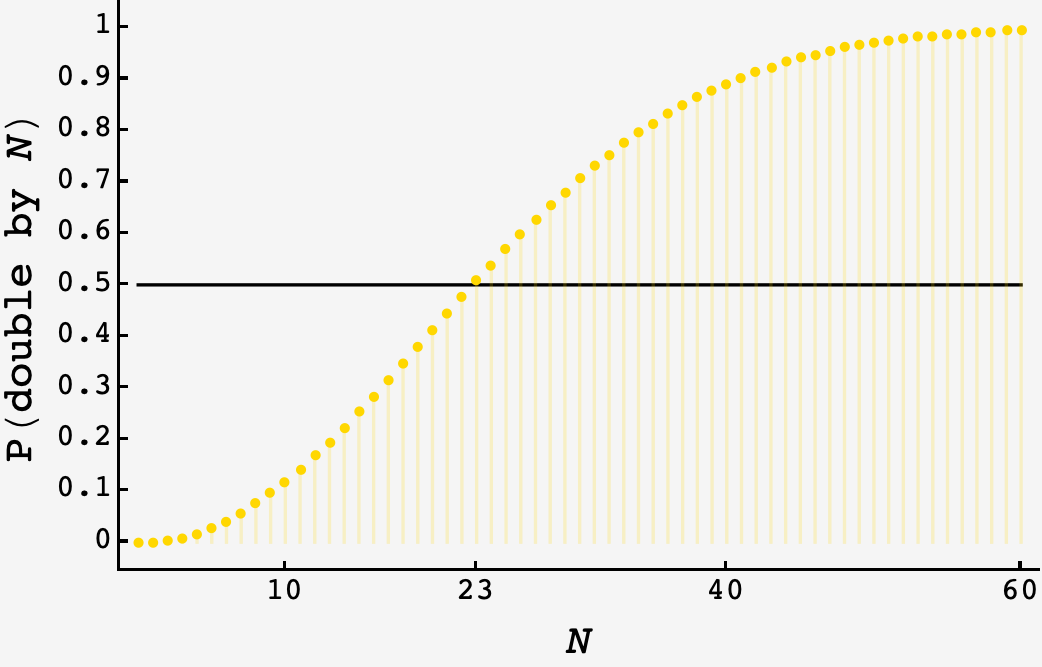

As expected, it crosses $50\%$ at $s=23.$

To find the probability that a room with $n$ people has no birthday triplets, we have to add up all the ways that $n$ people could have no triplets. For $n=5$ people, the relevant states are $(s,d) = (5,0),$ $(3,1),$ and $(1,2)$ corresponding to $5$ singlets, $3$ singlets plus $1$ pair of twins, and $1$ singlet plus $2$ pairs of twins.

So, adding over all $(s,d)$ on the frontier, the probability that there are no triplets in a group of $n$ or fewer people is

\[C(n) = \sum_{d=0}^{n/2} C(n-2d, d)\]CC[n_] := Sum[C[n - 2d, d], {d, 0, n/2}];

As before this is a cumulative probability ($\text{cdf}$), so the probability that the triplet first appears at $n$ people is $P(n) = C(n-1) - C(n).$

To find the average $\langle n\rangle$ we just sum

\[\langle n\rangle = \sum\limits_{n=3}^{2\cdot 365+1} n\left[C(n-1) - C(n)\right]\]Sum[n (CC[n - 1] - CC[n]), {n, 0, 2*365 + 1}]

which gives

188410800397516187399717065559037643830104811782677159115798873065426233643344881488297556659768225376857801014708780098231693129034794219061782328302736745996019262934317072871513609024966990149703977680765646997721439651174737983482772543346613862043047213432404687916815370111920464683273051476731788727278791656986688978131624635636809162183671539275622070083174154780244162282237255688364342656255187162264057523043944266115896563397162573107191448139181814293088129584723003717408509127290384960952228136228359361667292183342928834184420605078666184342989499478510278755755473909375074337802823223612531214656284387560467869873745906416510212353604520401788975806028716441073493463365675804015119323572436939590052364441857513996149806932959911540512374309693946591919660667917383946762549171980557462158154169309657995907945323927099907604222423925577536847578535300897265904177367453992908159846242437147456840105398991801959546186312013325212954955689979477808324812148857819805952861281831587795668738283226806010450597088072854856358582648503445167409058982431455439966032044163463263590998170583531790992966295970532797973472382034157707149489931480317891895521423982713688291133192835491592486992871506266907256368403452510277473471933135457542607783443107537439861184380281782020507915046030887210144588788653401371538489918192601873905853629908428123394376427982863592959412130731477062380606303382827950850832205560156001899527181186888633762899385710341946099772643584412721428603742669611312414064482763731890597804396868043414671308366071388400264334401597408244377102146383757427930847978088334778291999917034503310268841357409124922957868464591233665853422591623936306251148033219550563497627612490079328627 / 212320372375233561238686454192471324624544154861438536587497068174140187266910262370027185901464234395303337746623846608756349794263233979985075600704426120434692126124992229782407382262616403547902405438830946604658121960455869405058741361722913164607616999280440271485235631731312300290852673057306377247860760433988059150332632142937360450136452889041034731641429786132002486024661854855830987830516203245317090945594041669885995312394244491838768222033920537766713832274179322471154784441233870374758122861234846254469818391590186641373345243944191051157521767295929496643529483035000525566969681851135495287886135624017236364814144678501839016638267587877956299206688147262601911283645414917718166928042181204256527285661994048041450468945493603562473866745873740391315431488983375568019759997821574357375651598434893256737833220821234539760135829427770226083758364446058811246657677844714965360861091550576494551381489096992835557536264492935551403055295282100742899333220347994752650314630566161462691824077666146953903867079399890468518217628092832787809521461125099211583890385260103656197491250388643236017135400461522845743272990232411180694768648643439922464565428482489191416588691356821908952588637056050786108880387139780861569195923520724651053030920849520219448124084875526864128528083765993412269196108328055025640724914119562225125629740183864301980958251649384753782171515880768640510474740196981367361139281214907756070094304514739432402637694153565409003060414938298408320175131490709417324723226570726003294618659203979861715771052458582754337233052700633463024566345467379768702135279326340548345837219060365055706540046808619015723431739588086376542249395047313315076920048340980429202318191528320312

or approximately $88.74$

Combinatorics

The third approach is through counting. In the recursive section, we labeled the states using $(s,d).$ Now we’ll count how many ways $N(s,d)$ are there to form states $(s,d),$ with $n$ total people.

First we have to pick $(s+d)$ birthdays out of $365$ which gives a factor of $\binom{365}{s+d}.$ Next, we have to pick out how to assign singlets and doublets to the $(s+d)$ chosen birthdays which gives a factor of $\binom{s+d}{s}.$ Next there are $(s+2d)!$ ways to pick the order in which the people walk into the room. Finally, we don’t about the order in which two pairs of a doublet walk into the room, so we divide by $2^d.$ Putting it all together, the number of ways to pick form the state $(s,d)$ is

\[\Omega(s,d) = \dfrac{\dbinom{365}{s+d}\dbinom{s+d}{s}(s+2d)!}{2^d}.\]Now, we just sum over all possibly triplet free states $(s,d)$

\[N(\text{no triplets with }n\text{ people}) = \sum_{d=0}^{n/2}\Omega(n-2d,d)\]Finally, we have to divide by the number of ways to pick $n$ birthdays:

\[P(\text{no triplets with }n\text{ people}) = \dfrac{N(\text{no triplets with }n\text{ people})}{365^n}\]which gives the same results as the recursion.

Comparing exact and approximate results

What the extra work of the recursion/counting methods gets us are the built-in time lags that comes from e.g. singlets needing to precede doublets. In the approximation, it’s open season on collisions right from the get go, and the lags dissolve from view.

In each plot, the exact distribution is plotted in gold and the approximation in black.