Question: Data from the Event Horizon Telescope was recently used to generate a never-before-seen image of the black hole — Sagittarius A* — at the center of our galaxy. One of the most striking things about the image is how clearly we can make out the black hole’s shadow (as shown below). That’s because the plane of its accretion disk is nearly perpendicular to the vector between us and the black hole.

Was this likely to occur, or was it just a cosmic coincidence? Let’s find out. Assuming the accretion disk was equally likely to be in any plane, what is the probability of it being within 10 degrees of perpendicular to us, thereby resulting in a spectacular image?

Solution

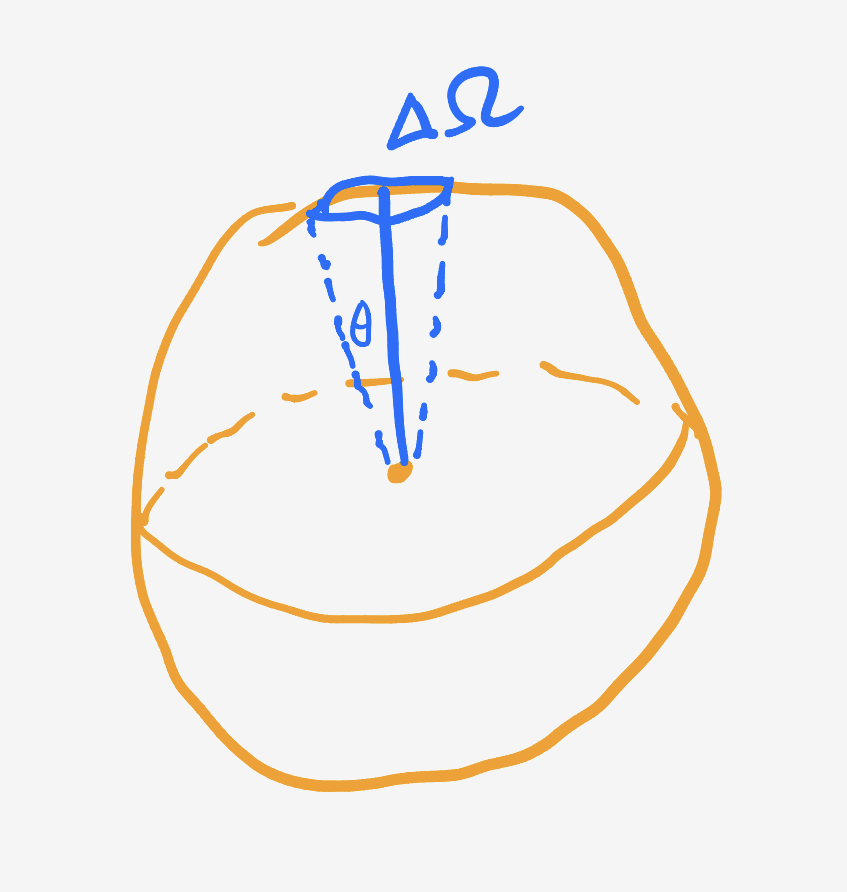

If Sag A*’s spin axis points toward Earth at random, then the probability is equal to the fraction of solid angles consistent with the alignment.

Approximate

Because $10^\circ$ is small patch of surface, curvature won’t mess things up too much and we can approximate the surface patch as a circle of radius $s = \theta.$

\[\begin{align} P(\text{Sag A}^*\text{ alignment}) &= \dfrac{\pi\theta^2}{4\pi} \\ &= \frac14 \left(\frac{10}{180}\pi\right)^2 \\ &\approx 0.007615, \end{align}\]which should be a bit of an overestimate.

Exact

For amusement, we can integrate the surface patch to find the exact solid angle:

\[\begin{align} \Delta \Omega &= 2\pi\int\limits_{0}^{\frac{10\pi}{180}}\sin\theta\, d\theta \\ &= 2\pi\left(1 - \cos\theta\right)\rvert_{\theta = \frac{10 \pi}{180}} \\ &\approx 0.007596. \end{align}\]Indeed, if we expand this to second order and divide by $4\pi,$ it becomes

\[\frac12\left(1 - 1 + \frac12\theta^2\right) = \frac14\theta^2,\]which is exactly what we got with the circle approximation.