Question:

Today marks the beginning of the Summer Olympics! One of the brand-new events this year is sport climbing, in which competitors try their hands (and feet) at lead climbing, speed climbing and bouldering.

Suppose the event’s organizers accidentally forgot to place all the climbing holds on and had to do it last-minute for their 10-meter wall (the regulation height for the purposes of this riddle). Climbers won’t have any trouble moving horizontally along the wall. However, climbers can’t move between holds that are more than 1 meter apart vertically.

In a rush, the organizers place climbing holds randomly until there are no vertical gaps between climbing holds (including the bottom and top of the wall). Once they are done placing the holds, how many will there be on average (not including the bottom and top of the wall)?

Extra credit: Now suppose climbers find it just as difficult to move horizontally as vertically, meaning they can’t move between any two holds that are more than 1 meter apart in any direction. Suppose also that the climbing wall is a 10-by-10 meter square. If the organizers again place the holds randomly, how many have to be placed on average until it’s possible to climb the wall?

Solution

First, some housekeeping. Neither problem changes if we rescale all lengths by so that the climbing wall is a unit square. This brings the gap from $\text{1 m}$ to the unitless $g^\prime = g/h = 1/10.$ Both problems are simpler to think about keeping it inside the unit square. With that out of the way, let’s begin.

The $1\text{D}$ climb

If there’s a climbable path from the bottom to the top, it means that there is no gap bigger than $g$ between consecutive holds.

Likewise, if there is no climbable path, it means that one or more holds are followed by a gap bigger than $g.$

For bookkeeping purposes, I’m going to consider the bottom of the climb as an obligatory hold, $h_0.$

Intuition with small number of holds

Suppose there are two placed holds, $h_1$ and $h_2.$ As long as $1/g > 3,$ it could be that there is a gap after $h_0$ or after $h_1$ or after $h_2:$

\[P(h_0) + P(h_1) + P(h_2).\]However, $P(h_0)$ and $P(h_1)$ both encompass $P(h_0 + h_1),$ which means that we are double counting $P(h_0 + h_1)$ (and $P(h_1 + h_2)$ and $P(h_2 + h_0)$). So, we subtract them off:

\[P(h_0) + P(h_1) + P(h_1) - P(h_0 + h_1) - P(h_1 + h_2) - P(h_2 + h_0).\]Here we fixed one problem, but caused another. Each of the $P(h_i)$ terms contain a copy of $P(h_0 + h_1 + h_2),$ as do each of the $P(h_i + h_j)$ terms, which means that it’s fully gone and we need to add it back in.

Finally, we have

\[\begin{align} P_\text{gap} = &+\left[P(h_0) + P(h_1) + P(h_2)\right] \\ &- \left[P(h_0 + h_1) + P(h_1 + h_2) + P(h_2 + h_0)\right] \\ &+ P(h_0 + h_1 + h_2). \end{align}\]The single gap probabilities $P(h_i)$ are $(1 - g)^2$ (two holds were not placed in a window of size $g$), the double gap probabilities $P(h_i + h_j)$ are $(1-2g)^2$ (two holds were not placed in a window of size $2g$), and the triple gap probability $P(h_0 + h_1 + h_2)$ is $(1-3g)^2,$ so

\[P_\text{gap} = \binom{3}{1}(1-g)^2 - \binom{3}{2} (1-2g)^2 + \binom{3}{3}(1-3g)^2.\]In general, there can be as many as $\lfloor g^{-1}\rfloor$ gaps (i.e. a minimal gap after the floor and every placed hold), and the probability of a gap with $h$ holds is

\[P_\text{gap}(h, g) = \sum_{x=1}^{\lfloor g^{-1}\rfloor} (-1)^{x+1} \binom{h}{x}(1-xg)^{h-1}.\]Likewise, the probability that the wall is climbable after $h$ or more holds is

\[P_\text{climb}(h, g) = 1 - P_\text{gap}(h, g).\]The probability that the wall first becomes climbable after placing the $h^\text{th}$ hold is

\[P_\text{climb}(h, g) - P_\text{climb}(h-1, g)\]And the expected number of holds that need to be placed to make the wall climbable is

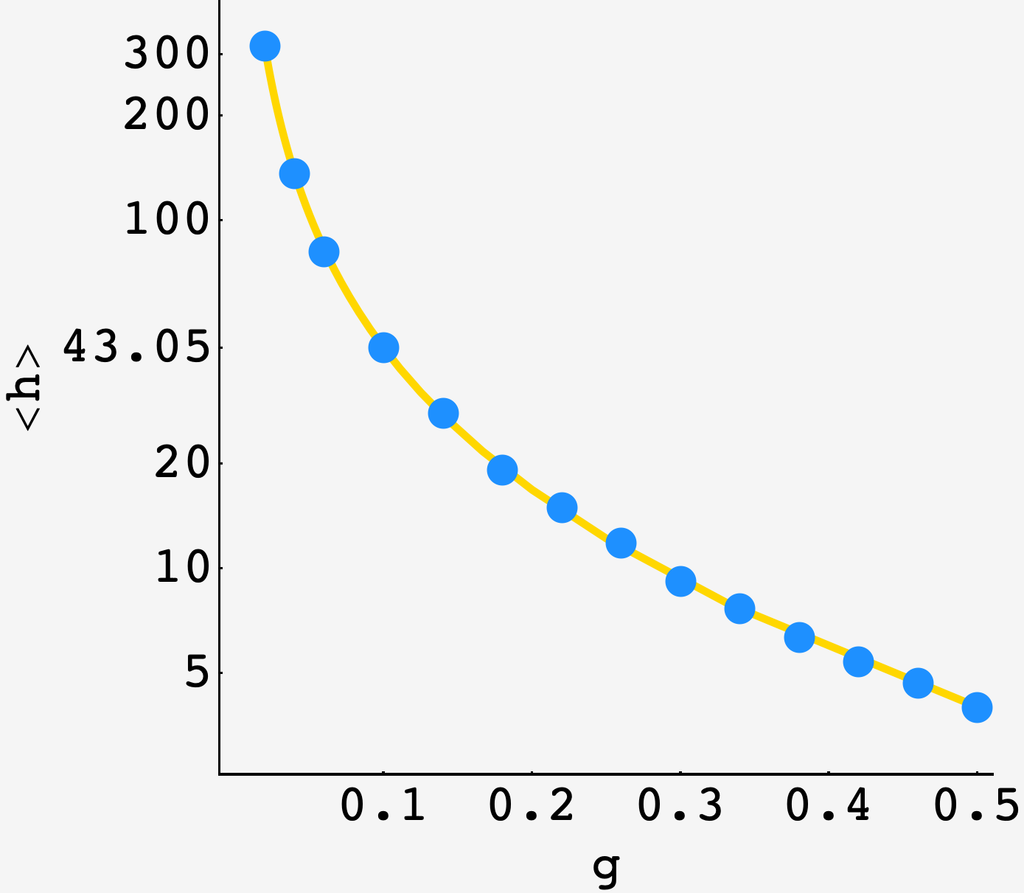

\[\langle h \rangle = \sum_{h=0}^\infty (h-1) \times\left[P_\text{climb}(h, g) - P_\text{climb}(h-1, g)\right]\]Plotting the prediction (gold) alongside an $N=1000$ round simulation (blue points), it’s pretty good.

For the case of the $1/10$ gap, we expect an average of precisely $43.0468…$ holds to be placed before the wall is climbable.

The $2\text{D}$ climb

When the climbing wall goes $2\text{D},$ my hopes for an analytical approach goes $0\text{D}.$

Turning to the computer, we need an algorithm that can efficiently check whether a set of $h$ holds contains a climbable path.

As a reminder, we need a path of holds from $y = 0$ to $y = 1,$ no two of which are more than $g$ away from each other. Also, the first and last holds need to be within $g$ of $y = 0$ and $y = 1,$ respectively.

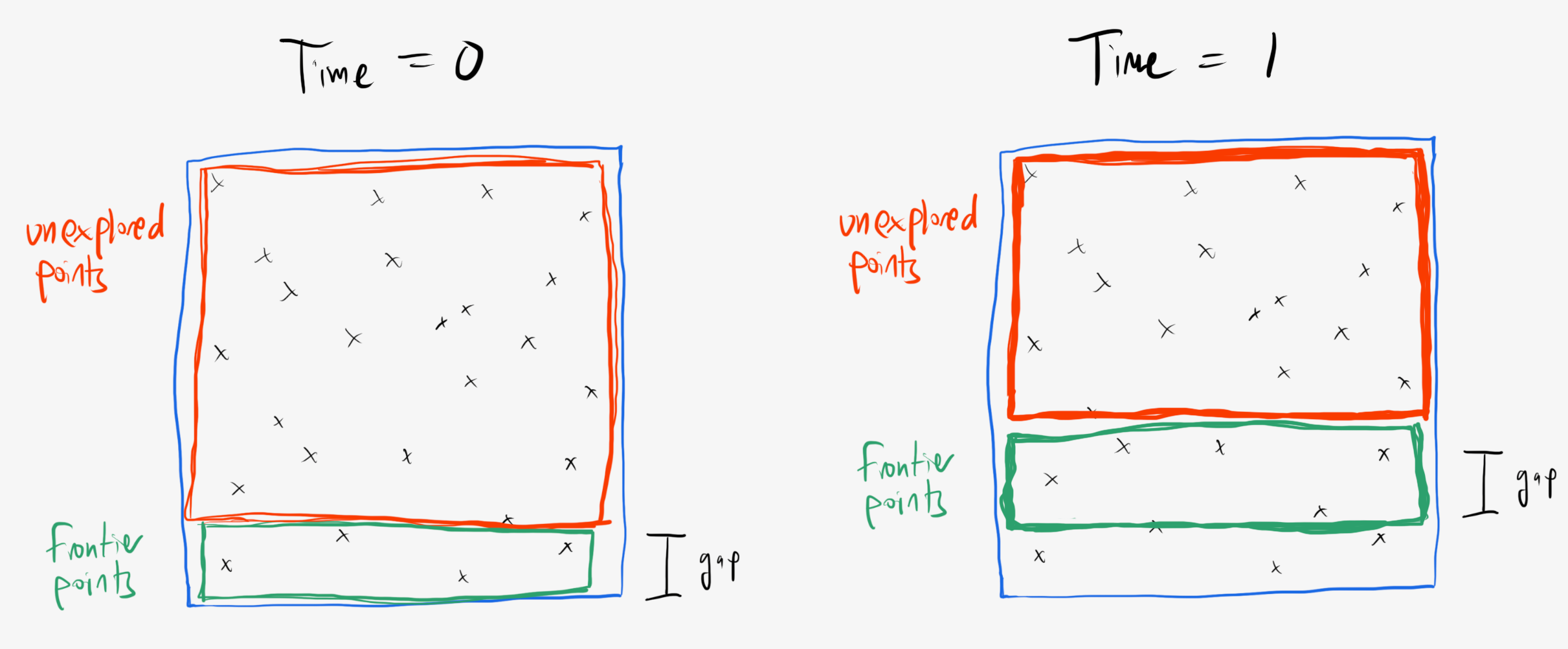

The essential logic is contained inside the function is_there_a_path(points, gap). The holds are divided into two groups, frontier points and unexplored points. To start, the frontier points are all the points within $g$ of $y = 0,$ and the unexplored points are the rest of the points.

Each round, the set of points that are within $g$ of a current frontier point become the new frontier points, and the unexplored points become all the points that have yet to be frontier points.

At the start of each round, we check whether there is a frontier point that’s within $g$ of $y = 1.$ If so, then the algorithm returns True, otherwise, it keeps going.

If we get to a point where there are no further frontier points, and no climbable path has been found, then it definitively returns False.

import random

def distance(pt1, pt2):

return ((pt1[0] - pt2[0]) ** 2 + (pt1[1] - pt2[1]) ** 2) ** 0.5

def is_there_a_path(points, gap):

frontier_points = {pt for pt in points if pt[1] < gap}

unexplored_points = points - frontier_points

if len(frontier_points) == 0:

return False

while len(frontier_points) > 0:

if any(pt[1] > (1 - gap) for pt in frontier_points):

return True

temp_frontier_points = set()

for frontier_pt in frontier_points:

for unexplored_pt in unexplored_points:

if distance(frontier_pt, unexplored_pt) < gap:

temp_frontier_points.add(unexplored_pt)

frontier_points = temp_frontier_points

unexplored_points = unexplored_points - frontier_points

return False

We measure $\langle h\rangle$ using a while loop that adds random holds to the wall one by one, checking whether a climbable path exists after each point is added.

def round(gap):

points = {(random.random(), random.random())}

while not is_there_a_path(points, gap):

points.add((random.random(), random.random()))

return len(points)

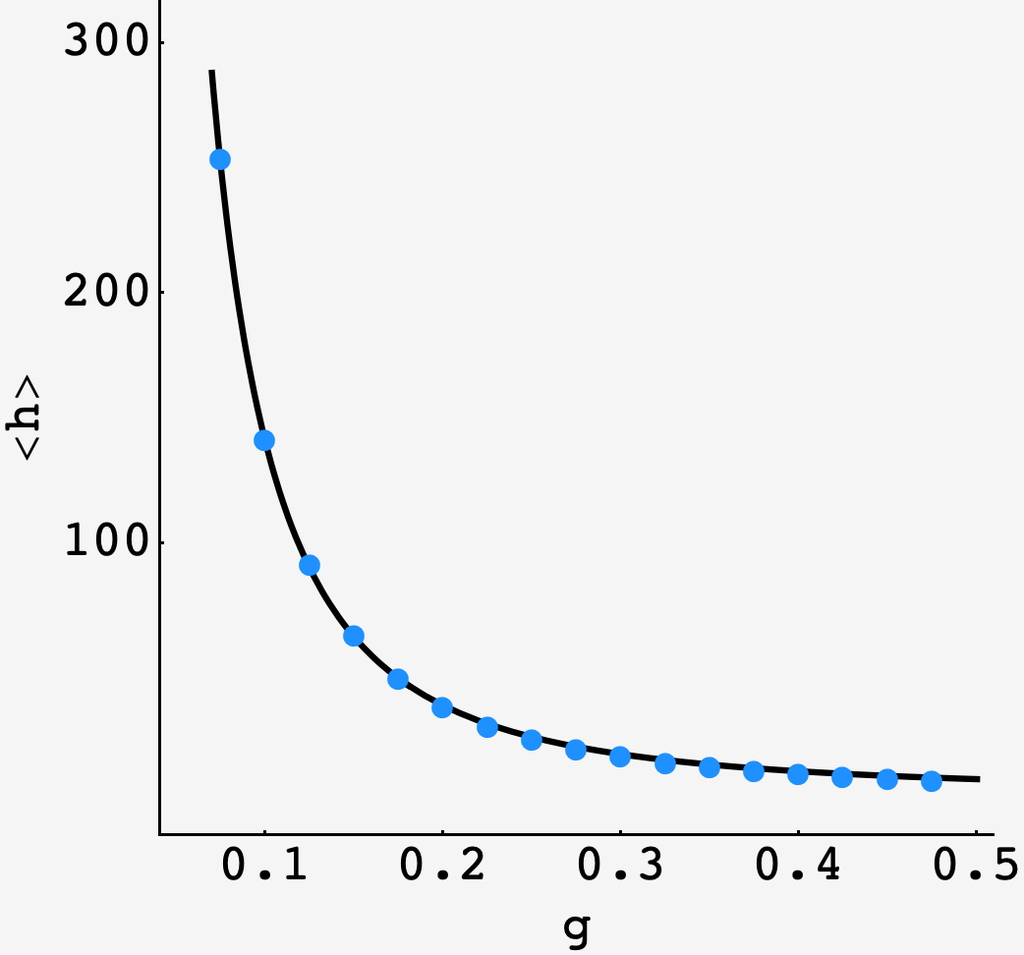

Running this for $g \leq 0.5,$ we get

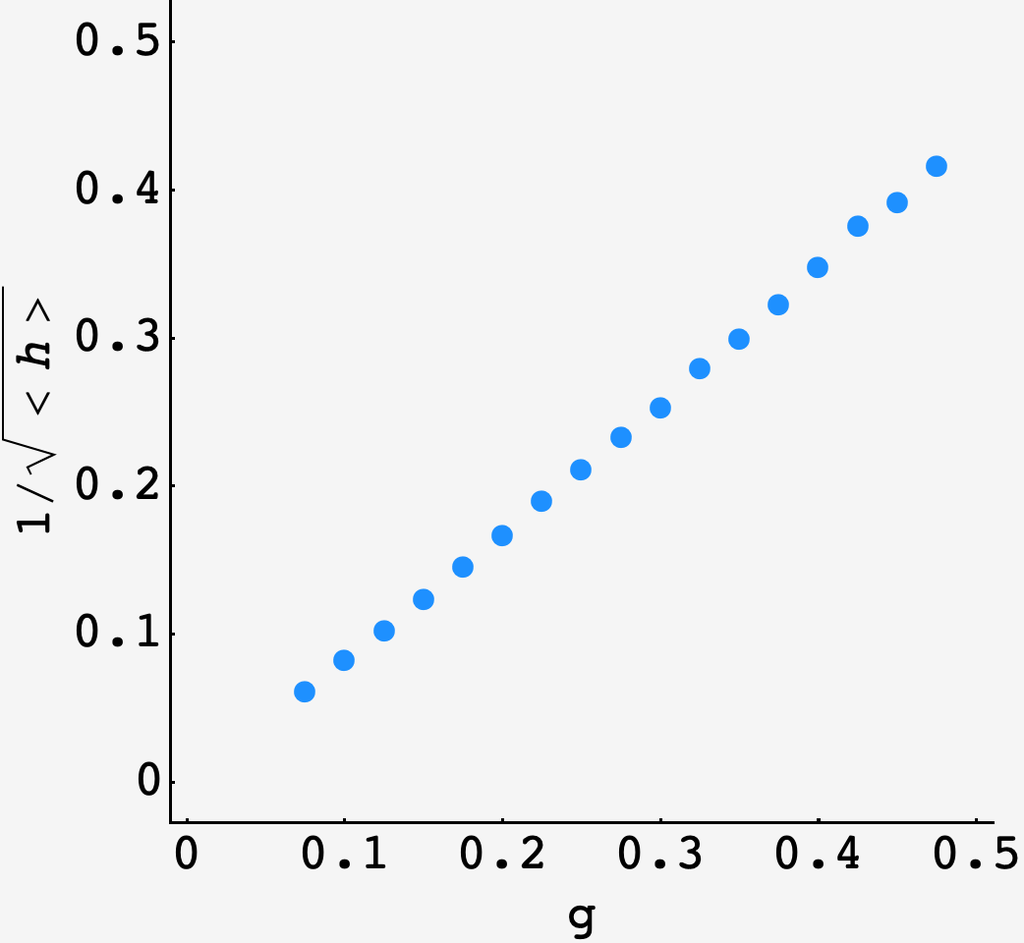

The black line is the trial function $1.4/g^2.$ The inverse square of the gap length captures the shape of the curve remarkably well, which is clear from the plot below:

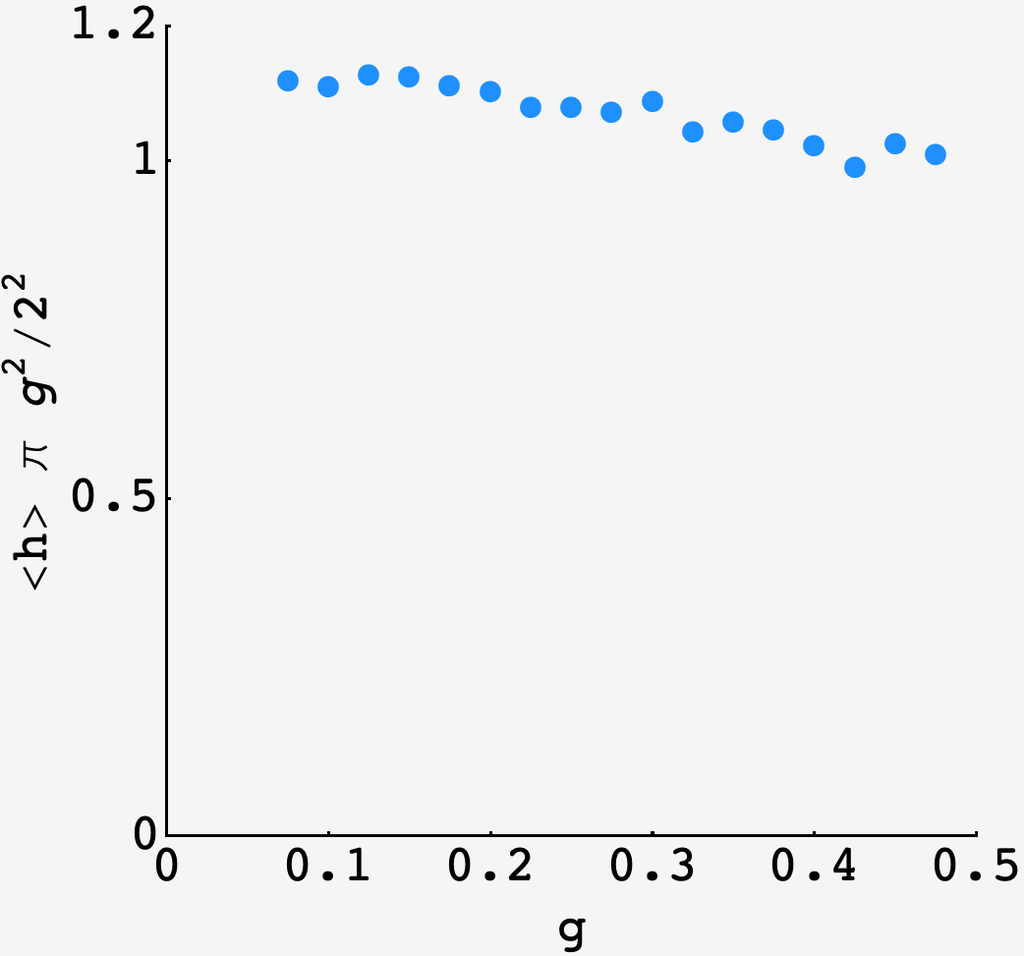

Another way to look at the expected number of placed holds is as a number density: $\rho_N = \langle h\rangle \approx \text{const.}/g^2.$

As a single placed hold takes up the area $A_h = \pi g^2,$ the total area swept out by the holds is $\rho = \rho_N A_h \approx \text{const.}$ In other words, we expect the wall to be climbable as soon as the total (redundant) area accessible to the holds is above an invariant threshold.

Plotting $\rho,$ we find an approximately constant curve

which shows that $\text{const.} \approx 1.08.$

For the case of $1/10$ gaps, we expect approximately $143$ holds to be placed before the wall is climbable.