Question: The Robot Weightlifting World Championship’s final round is about to begin! Three robots, seeded 1, 2, and 3, remain in contention. They take turns from the 3rd seed to the 1st seed publicly declaring exactly how much weight (any nonnegative real number) they will attempt to lift, and no robot can choose exactly the same amount as a previous robot. Once the three weights have been announced, the robots attempt their lifts, and the robot that successfully lifts the most weight is the winner. If all robots fail, they just repeat the same lift amounts until at least one succeeds.

Assume the following:

- all the robots have the same probability $p(w)$ of successfully lifting a given weight $w$;

- $p(w)$ is exactly known by all competitors, continuous, strictly decreasing as the w increases, $p(0) = 1,$ and $p(w) \rightarrow 0$ as $w \rightarrow \infty$; and

- all competitors want to maximize their chance of winning the RWWC.

If $w$ is the amount of weight the 3rd seed should request, find $p(w).$ Give your answer to an accuracy of six decimal places.

Solution

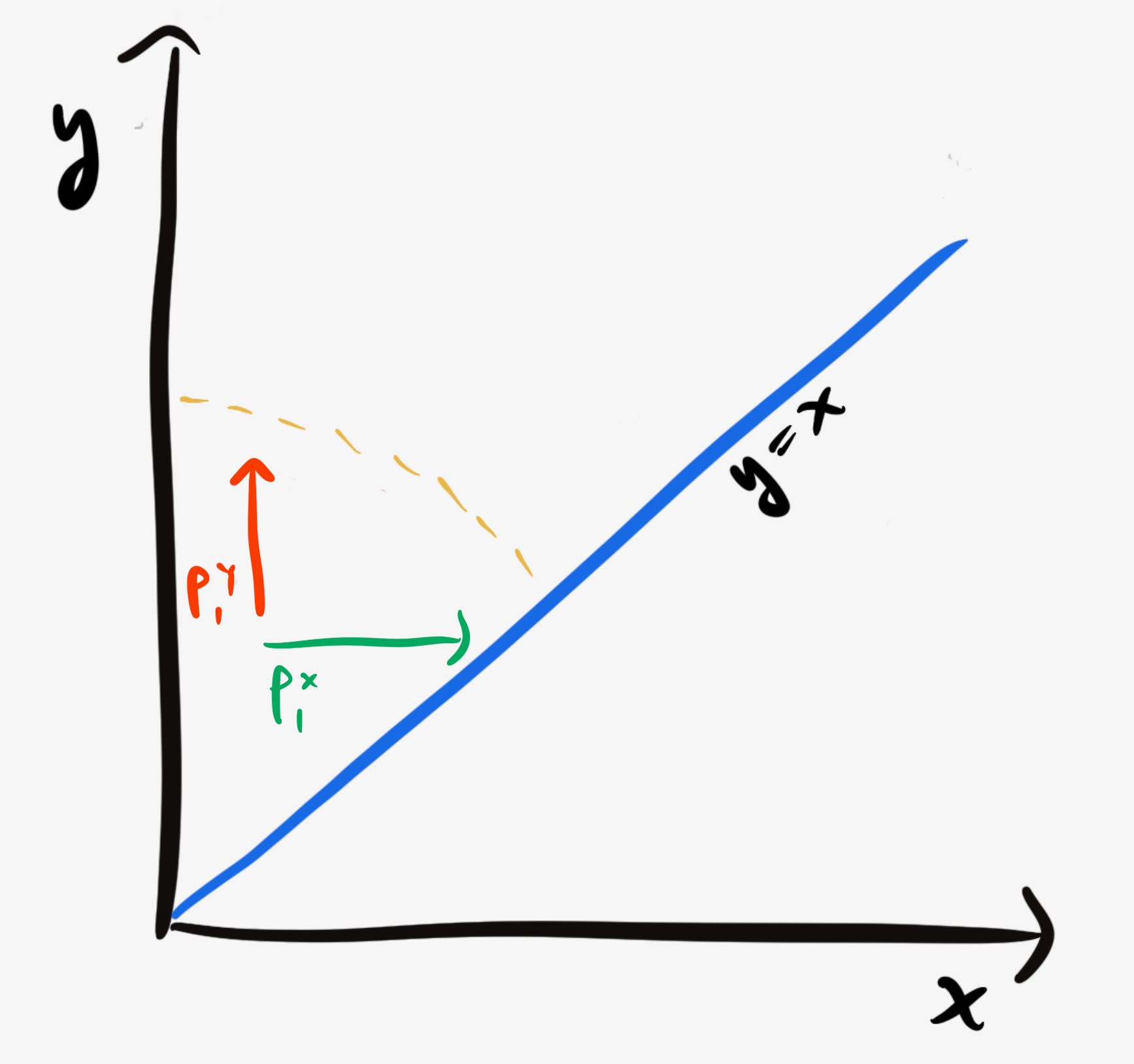

When the first seed’s time comes, they find a betting landscape set by the bets of $x$ and $y.$ They have three materially different choices: frontrun $x,$ frontrun $y,$ or bet behind $y.$

Player 1, X and Y’s chances to win

As an illustrative example, suppose that Player 1 decides to frontrun Player Y, so that $x < z < y.$ For Player 1 to win a round in this case, they need their lift to succeed (probability $x$) and Player X’s lift to fail (probability $1-x$), since a successful heavier lift would beat them. Similarly, Player Y needs their lift to succeed (probability $y$), and the other two to fail (probability $(1-x)(1-z).$ However, these three outcomes aren’t exhaustive… it is possible for noone to win the round, in which case the game starts over. So, we have to normalize by the chance that something happens, $1-(1-x)(1-y)(1-z).$

By this logic, Player 1’s chances in the three situations are ($z$ is Player 1’s lift probability)

\[\frac{z}{1-(1-x)(1-y)(1-z)},\] \[\frac{z(1-x)}{1-(1-x)(1-y)(1-z)},\]and

\[\frac{z(1-x)(1-y)}{1-(1-x)(1-y)(1-z)}.\]These are monotonically increasing in $z,$ so Player 1 only has to consider $x,$ $y,$ and $1.$ When this is done, the chances for each player in the three scenarios are

\[\begin{array}{|c|l|l|l|} \hline \text{Player 1's bet} & \text{Player 1 odds} & \text{Player}\, x\,\text{odds} & \text{Player}\, y\,\text{odds} \\ \hline 1 & P_1^1 = (1-x)(1-y) & P_1^X = x & P_1^Y = y(1-x) \\ \hline x & P_X^1 = \dfrac{x}{1-(1-x)^2(1-y)} & P_X^X = \dfrac{x(1-x)}{1-(1-x)^2(1-y)} & P_X^Y = \dfrac{y(1-x)^2}{1-(1-x)^2(1-y)} \\ \hline y & P_Y^1 = \dfrac{y(1-x)}{1-(1-x)(1-y)^2} & P_Y^X = \dfrac{x}{1-(1-x)(1-y)^2} & P_Y^Y = \dfrac{y(1-x)(1-y)}{1-(1-x)(1-y)^2} \\ \hline \end{array}\]Player 1 will pick whichever of their three options is greatest, given the values of $x$ and $y:$

\[\text{Player 1's bet} = \max\{P_X^1(x,y), P_Y^1(x,y), P_1^1(x,y)\}.\]The betting landscape

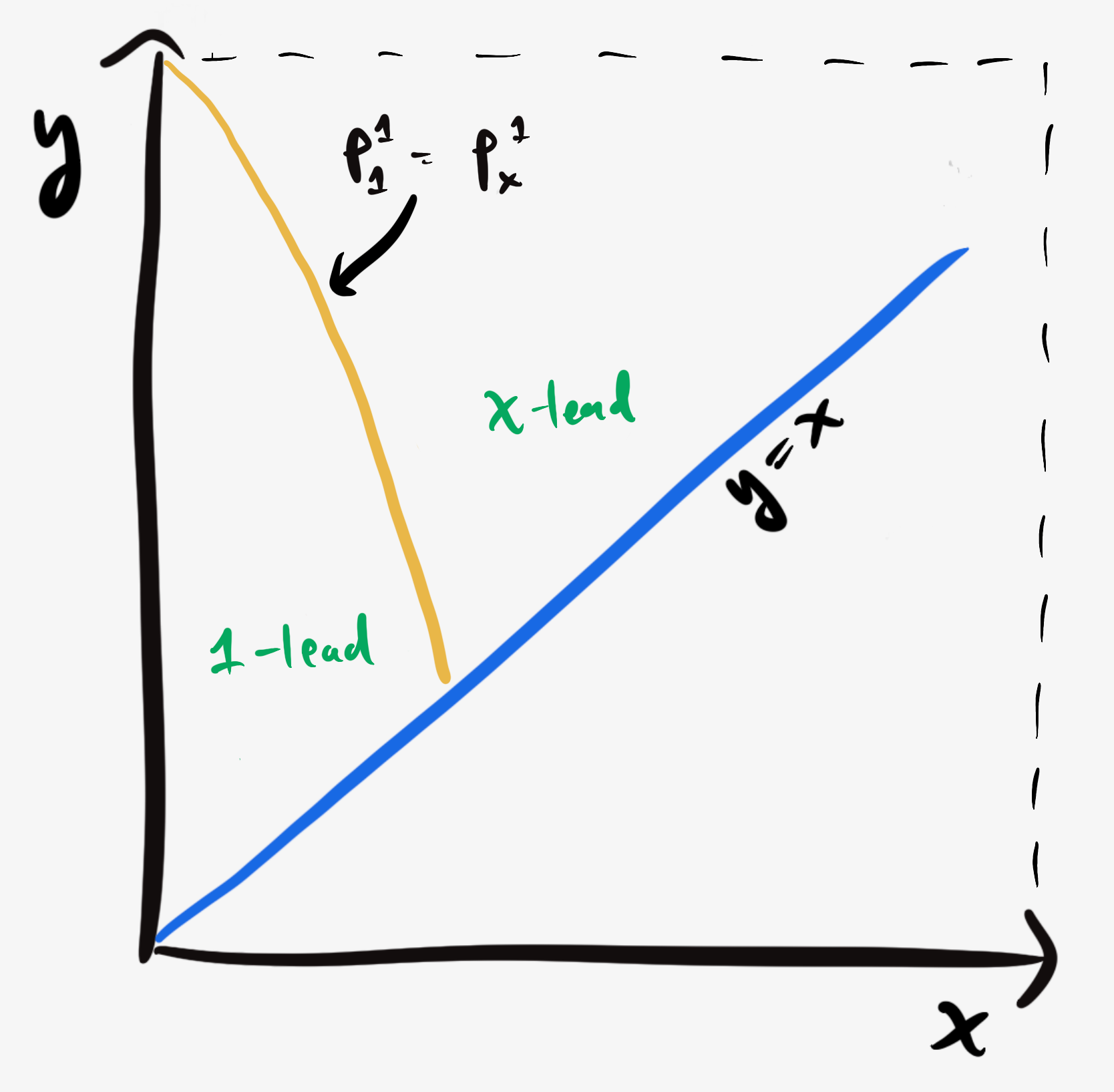

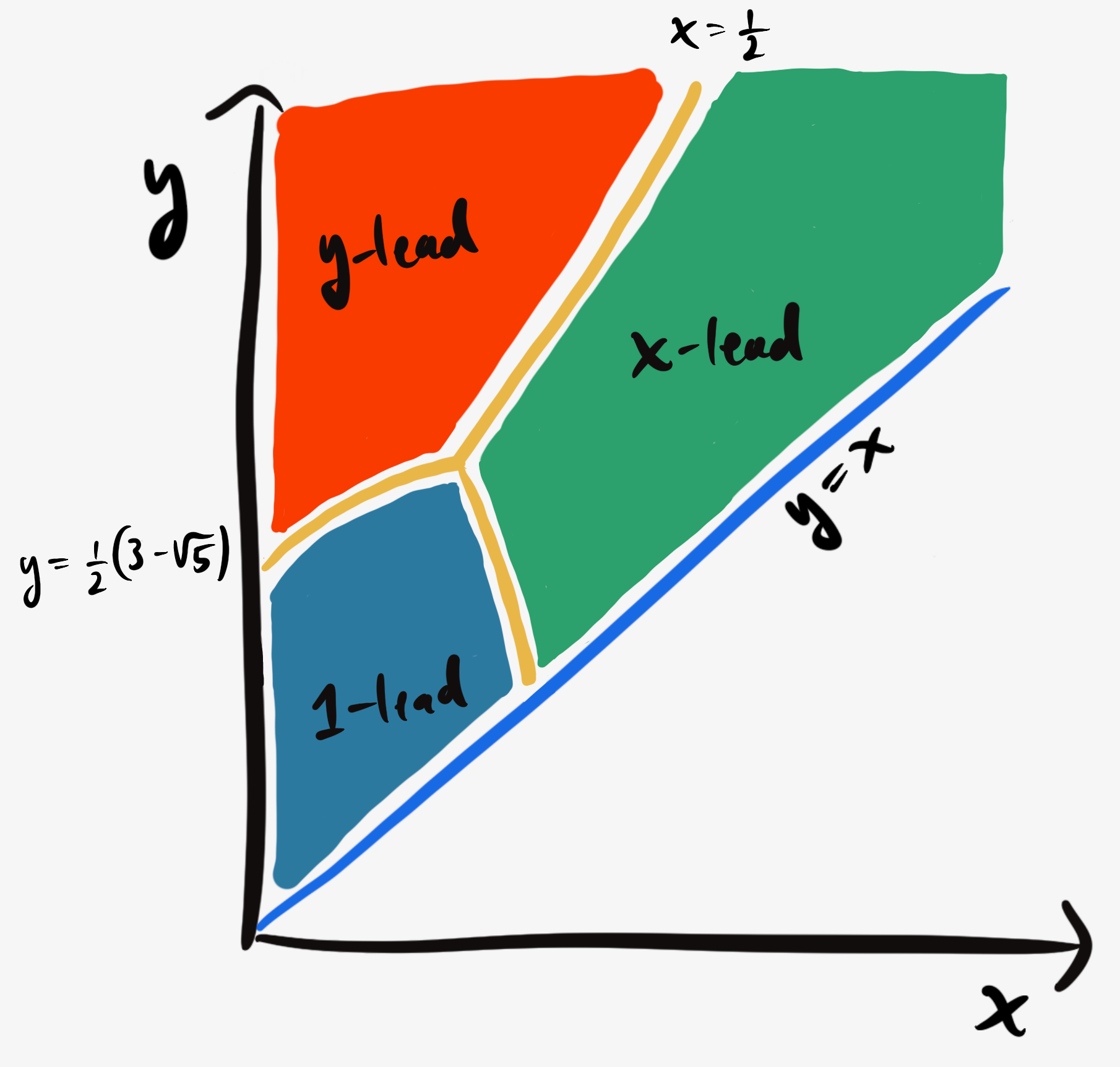

The betting landscape is defined by the $\max$ function above, which defines an optimal bet for Player 1 for every possible pair $(x,y)$.

For small $x$ and $y,$ $P_1^1(x,y)$ is Player 1’s best choice: Players X and Y are unlikely to succeed in their lifts, so Player 1 can lift zero weight and usually win.

In this regime, Player X and Player Y’s chances are simply $x$ and $y(1-x)$ and both can increase their chances by setting their lift probability as high as possible.

Player 1 will continue to bet $1$ up until the point where $P_X^1(x,y) = P_1^1(x,y).$ Past that border, it becomes advantageous for them to undercut Player X by betting just under $x.$ This curve bends up and to the left, since for larger values of $y,$ it is less likely for Players X and Y to both fail in their lifts.

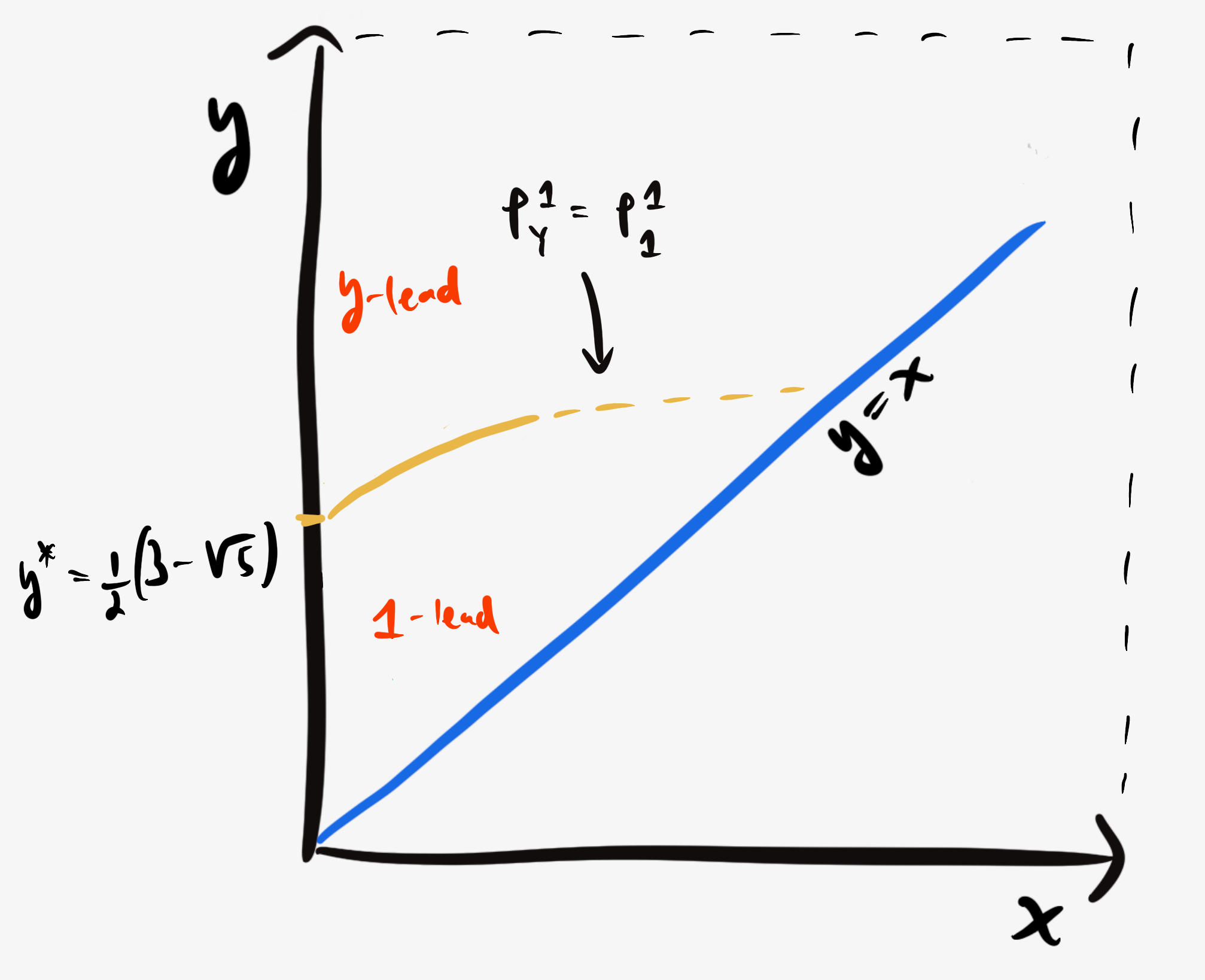

Similarly, if $y$ becomes big enough so that $P_Y^1(x,y) = P_1^1(x,y)$, Player 1 will switch their bet to just under $y.$ This curve bends up and to the right since for higher values of $x,$ $y$ will have to be bigger to outcompete $x$ as the more attractive undercutting opportunity. This border intersects the $y$-axis at $y^* = \frac12\left(3-\sqrt{5}\right)$ (obtained by solving ${P_Y^1(0,y) = P_1^1(0,y)}$).

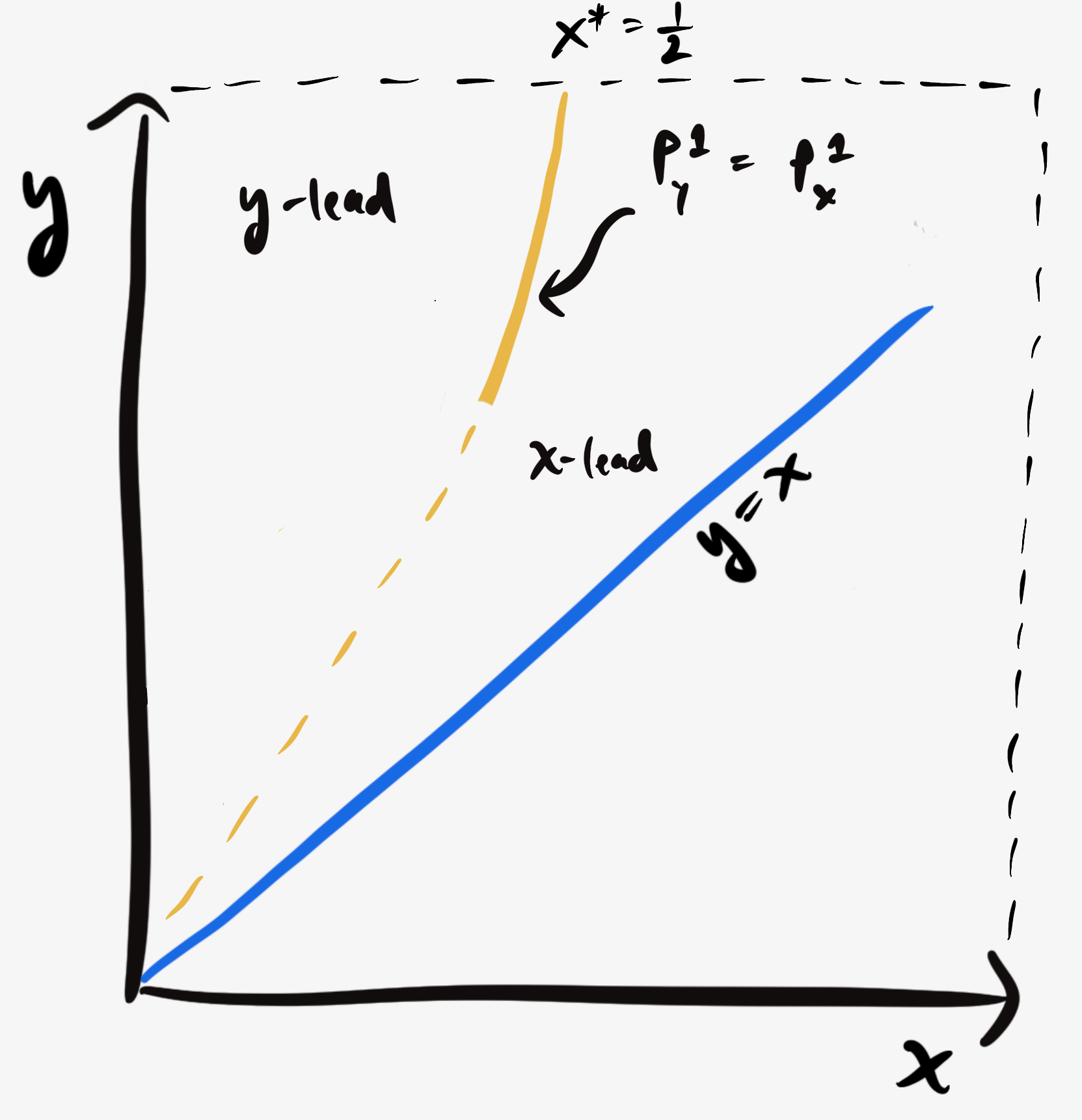

If $x$ and $y$ are both large, then it’s no longer attractive for Player 1 to bet $1$ and they will always undercut Player X or Player Y. The border between the regimes is given by the curve $P_X^1(x,y) = P_Y^1(x,y),$ which curves up and to the right since as $x$ grows, $y$ will have to be more and more of a sure bet to outcompete the comparitively sure bet in $x.$ This curve hits the boundary of the square (${y=1}$) when ${x^*=\frac12.}$

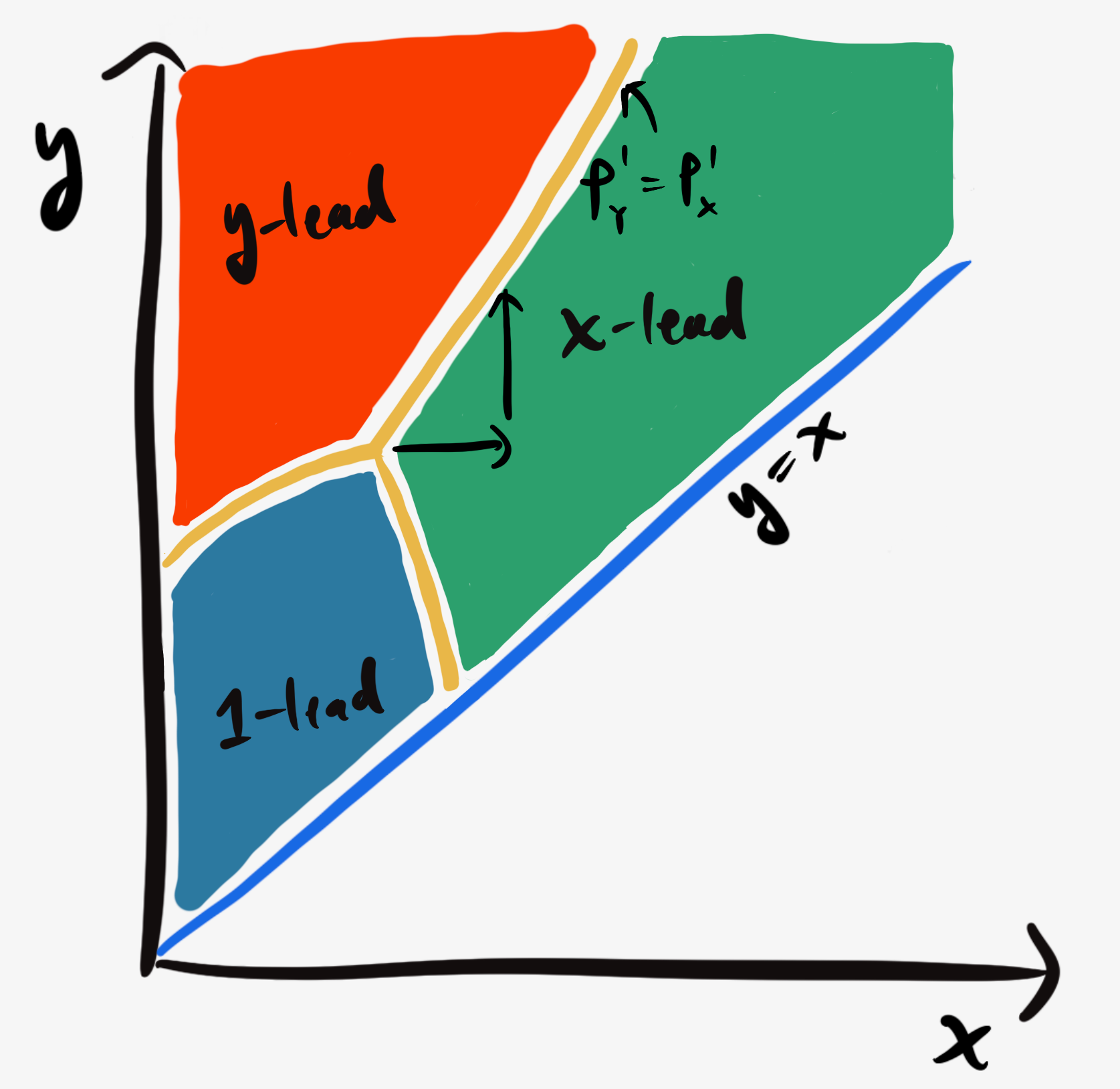

As there are three zones, with borders between each pair, there is one point where the three strategies are equally attractive to Player 1, and the betting landscape looks like:

The triple point can be found by solving the intersection of any two of these borders, and we get $x_\text{triple} \approx 0.2868\ldots$ and $y_\text{triple} \approx 0.4360\ldots$

Incentives for Players X and Y in the $1$-lead

In the $1$-lead, Players X and Y are incentivized to set $x$ and $y$ as high as possible. Naively, Player X can achieve this by setting $x$ to where the $P_1^1(x,y)=P_X^1(x,y)$ border crosses $y=x.$

But in this case, Player Y benefits by bringing the game (at least) into the $x$-lead, and making $y$ as large as possible there. This means that any foray past the triple point will bring the game up to the $P_Y^1(x,y) = P_X^1(x,y)$ border.

How does Player X fare there? We can solve for when the slope of $P_X^X(x,y)$ is less than zero: ${\partial_x P_X^X(x,y) < 0 }$ which gets

\[y \gt \dfrac{x^2}{(1-x)^2}.\]Now, by definition, $P_Y^1(x,y) = P_X^1(x,y)$ along the border, so

\[\dfrac{y(1-x)}{1-(1-x)(1-y)^2} = \dfrac{x}{1-(1-x)^2(1-y)}.\]Since $(1-x) > (1-y),$ this means that $y(1-x) > x,$ or $y > x/(1-x).$

The border ends at $x = \frac12,$ so $x/(1-x) < 1$ for all relevant values of $x,$ and so

\[\begin{align} y &\gt \frac{x}{1-x} \\ &\gt \left(\dfrac{x}{1-x}\right)^2. \end{align}\]This means that $P_X^X(x,y)$ decreases monotonically as we move along the border away from the triple point, and Player X does not benefit in bringing the game up to the $P_1^1(x,y) = P_X^1(x,y)$ border (this is the reason we only need to consider $x \leq y$).

So far, this means that Player X’s best chance is at the triple point. Likewise, Player Y’s chance is at least ${P_1^Y(x_\text{triple},y_\text{triple}) = y_\text{triple}\left(1-x_\text{triple}\right)}.$

North of the border

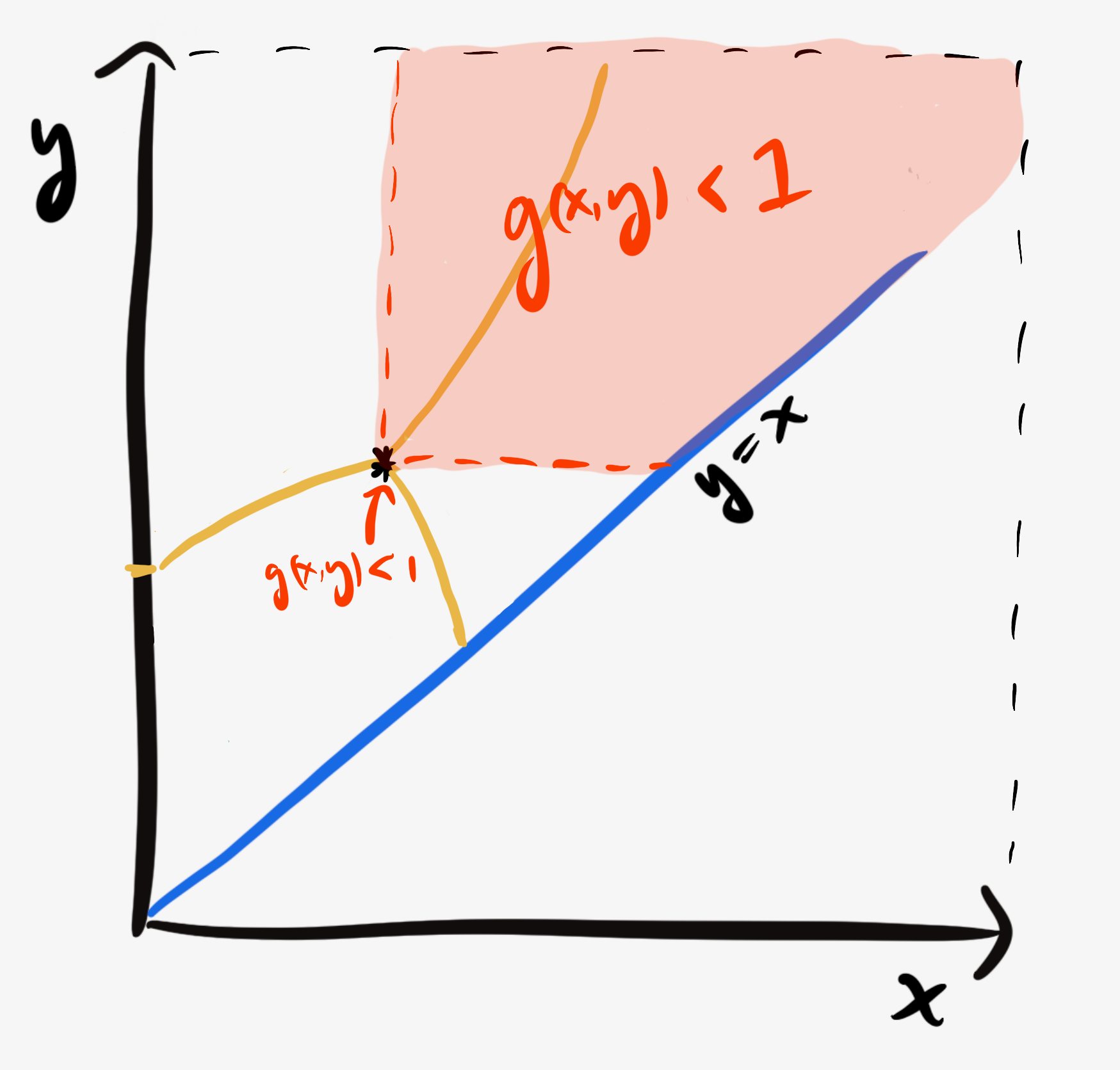

What happens if Player Y crosses the $P_1^1(x,y) = P_Y^1(x,y)$ border?

On the other side of the border, Player 1 will undercut them and their chances become

\[\begin{align} P_Y^Y(x,y) &= \frac{y(1-y)(1-x)}{1-(1-x)(1-y)^2} \\ &= y(1-y)\times g(x,y). \end{align}\]Since $(1-x) > (1-y),$

\[\frac{(1-x)}{1-(1-x)(1-y)^2} < \frac{1-x}{1-(1-x)^2(1-y)}.\]At the triple point

\[\begin{align} f(x,y) &= \frac{1-x}{1-(1-x)^2(1-y)} \\ &= 1, \end{align}\]so $g(x,y) < f(x,y) = 1.$

$g(x,y)$ decreases monotonically in $x$ and $y,$ so $g(x,y) < 1$ for all points up and to the right of the triple point, which means that $P_Y^Y(x,y) = y(1-y)g(x,y) \lt \frac14$ for those points too.

Since $P_1^Y(x_\text{triple}, y_\text{triple}) = y_\text{triple}(1-x_\text{triple}) \approx 0.311 > \frac14$ at the triple point, Player Y doesn’t stand to gain anything by moving above it.

Putting it all together:

- Player X will make $x$ as high as possible without allowing Player Y to move the game into $x$-lead territory, and

- Player Y will make $y$ as high as possible without bringing the game into $y$-lead territory.

- $x$-lead territory lies across the $P_1^1(x,y) = P_X^1(x,y)$ border and $y$-lead territory lies across the $P_1^1(x,y) = P_Y^1(x,y)$ border.

This means that the point where the $P_1^1(x,y) = P_Y^1(x,y)$ and $P_1^1(x,y) = P_X^1(x,y)$ borders intersect is optimal for Players X and Y.