Question: it’s election night and your candidate is behind in the count. However, a significant fraction of the vote is still out in uncounted mail-in ballots. What are the chances that your candidates come back for the stunning victory if a whole bunch of people vote? What happens when the polls are tilted in one direction?

Solution

The trick we’re interested in is for the loser on election night to go on to be the winner when all is said and done. For the case at hand, this means that, on election night, a candidate has less than $\frac12 n_1$ (half of the votes), but gets enough in the mail-ins to end up with over half of the total votes (more than $\frac12 (n_1 + n_2)$).

\[P(\text{less than half on election night, but majority overall})\]Each person’s vote is independent, so the probability that candidate $A$ gets $A_i$ votes total out of a bundle of $n_i$ votes is

\[P(A_i, n_i) = \binom{n_i}{A_i} p^{A_i} (1-p)^{n_i - A_i}.\]The overall probability of a comeback is the sum over all possible vote totals $A_1$ and $A_2$ that satisfy the conditions we laid out above:

\[P(\text{comeback}) = \sum_{A_1, A_2} P(A_1, n_1) \times P(A_2, n_2)\]Respect your limits

The greatest number of votes the election night loser can get, yet still go on to win is one less than half the votes counted on election night, ($\frac12 n_1 - 1$). Similarly, the least number of votes that a comeback candidate can get on election night is $1$ more than half the total number of votes minus all the mail-in votes ($1 + \frac12 (n_1 + n_2) - n_2).$

Given $A_1$ votes on election night, the fewest votes the comeback candidate can get in the mail-ins is $A_1$ fewer than one more than half the total votes, $(1 + \frac12 (n_1 + n_2) - A_1).$ The greatest number of votes they can get is just all of the available mail-in votes, $n_2.$

Add ‘em up

Putting this together, we have an answer for a finite voting population

\[P(\text{comeback}) = 2\sum_{A_1 = 1 + \frac12(n_1 + n_2) - n_2}^{\frac12 n_1 - 1}\,\sum_{A_2 = 1 + \frac12(n_1+n_2) - A_1}^{n_2} P(A_1, n_1)\times P(A_2 n_2)\]If, say, our population had $100$ people, then $n_1 = 80,$ $n_2 = 20,$ and

\[\begin{align} P(\text{comeback}) &= \frac{24161233910133742271486959445}{633825300114114700748351602688} \\ &\approx 0.0762394 \end{align}\]However, our population has many, many people, so this simply will not do.

Open the gates

For small populations, we can feel the discrete nature of the vote’s binomial distribution, with substantial jumps at vote totals around the mean. But, when the population gets big, the binomial distribution smooths out and closely resembles a Gaussian of the same mean and variance. We get

\[P(A, n) = \binom{n}{A}p^A(1-p)^{n-A} \rightarrow \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi n p(1-p)}} e^{-(A-np)^2/2np(1-p)}\]Turning the sums into integrals, it becomes (the $1$s go to zero)

\[P(\text{comeback}) = 2\int\limits_{\frac12(n_1 - n_2)}^{\frac12 n_1} dA_1 \int\limits_{\frac12(n_1+n_2) - A_1}^{n_2} dA_2\, P(A_1,n_1)\times P(A_2,n_2)\]For now, we can set $p$ to $\frac12$

\[\frac{4}{\pi\sqrt{n_1 n_2}}\int\limits_{\frac12(n_1 - n_2)}^{\frac12 n_1} dA_1 \int\limits_{\frac12(n_1+n_2) - A_1}^{n_2} dA_2\, e^{-2(A_1-\frac12n_1)^2/n_1} e^{-2(A_2-\frac12n_2)^2/n_2}\]The exponentials suggest the new variables $A_1^\prime = A_1 - \frac12 n_1$ and $A_2^\prime = A_2 - \frac12 n_2.$ Applying these transformations to the limits

\[\frac{4}{\pi\sqrt{n_1 n_2}}\int\limits_{-\frac12n_2}^{0} dA_1^\prime\, e^{-2{A_1^\prime}^2/n_1} \int\limits_{-A_1^\prime}^{\frac12n_2} dA_2^\prime\, e^{-2{A_2^\prime}^2/n_2}.\]Because the exponential dies quickly away from the mean, we can replace the $\frac12 n_2$s in the limits by $\infty,$ and

\[\frac{4}{\pi\sqrt{n_1 n_2}}\int\limits_{-\infty}^{0} dA_1^\prime\, e^{-2{A_1^\prime}^2/n_1} \int\limits_{-A_1^\prime}^{\infty} dA_2^\prime\, e^{-2{A_2^\prime}^2/n_2}.\]The inner integral produces the complementary error function and the outer integral can be found in the “compendium of indefinite and definite integrals of products of the Error function with elementary or transcendental functions.”

Putting this together, $P(\text{comeback})$ becomes

\[\frac12 - \frac{1}{2\pi}\arctan\sqrt{\frac{n_1}{n_2}}\]or, letting $n_1 = fN$ and $n_2 = (1-f)N,$

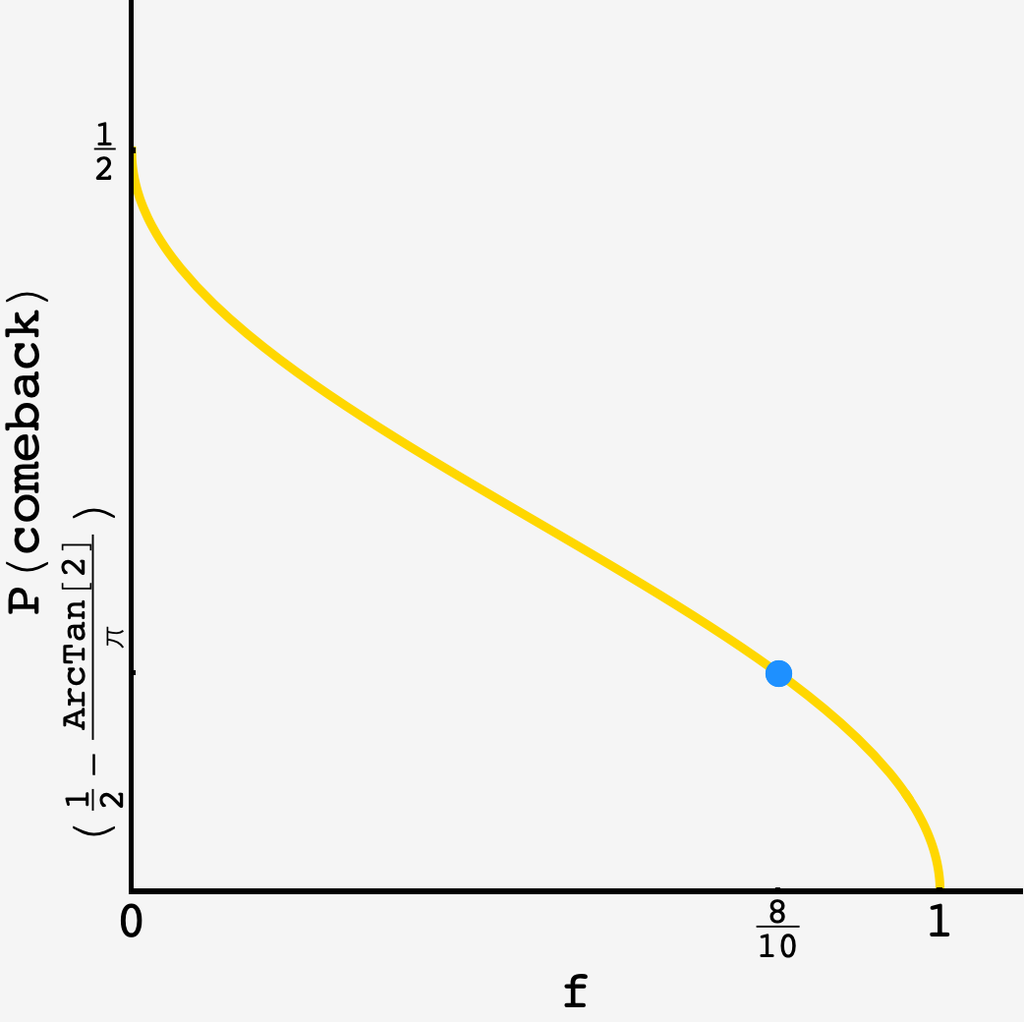

\[P(\text{comeback}) = \frac12 - \frac{1}{2\pi}\arctan\sqrt{\frac{f}{1-f}}\]which, for $f = 8/10$ comes out to $\approx 0.147584$

Real elections

In a real election, $p \neq \frac12,$ so what should we expect then? If we work through the change of variables without setting $p$ to $\frac12,$ we arrive at more interesting integration limits:

\[\int\limits_{n_1(\frac12 -p)-\frac12 n_2}^{n_1(\frac12-p)}dA_1^\prime\,\int\limits_{(n_1+n_2)(\frac12-p)-A_1^\prime}^{n_2(1-p)}dA_2^\prime\,\text{(the integrand)}.\]If $p > \frac12$ then both the lower and upper limit on the outer integral go to $-\infty$ and $P(\text{comeback})$ goes to zero when we take the limit of large $n_1, n_2.$ Likewise, if $p < \frac12$ then both the lower and upper limit on the outer integral go to $+\infty,$ again bringing $P(\text{comeback})$ to zero.

In effect, this comeback phenomena can only happen when $p$ is precisely equal to $\frac12.$ Literally any other value will drive $P(\text{comeback})$ to zero.

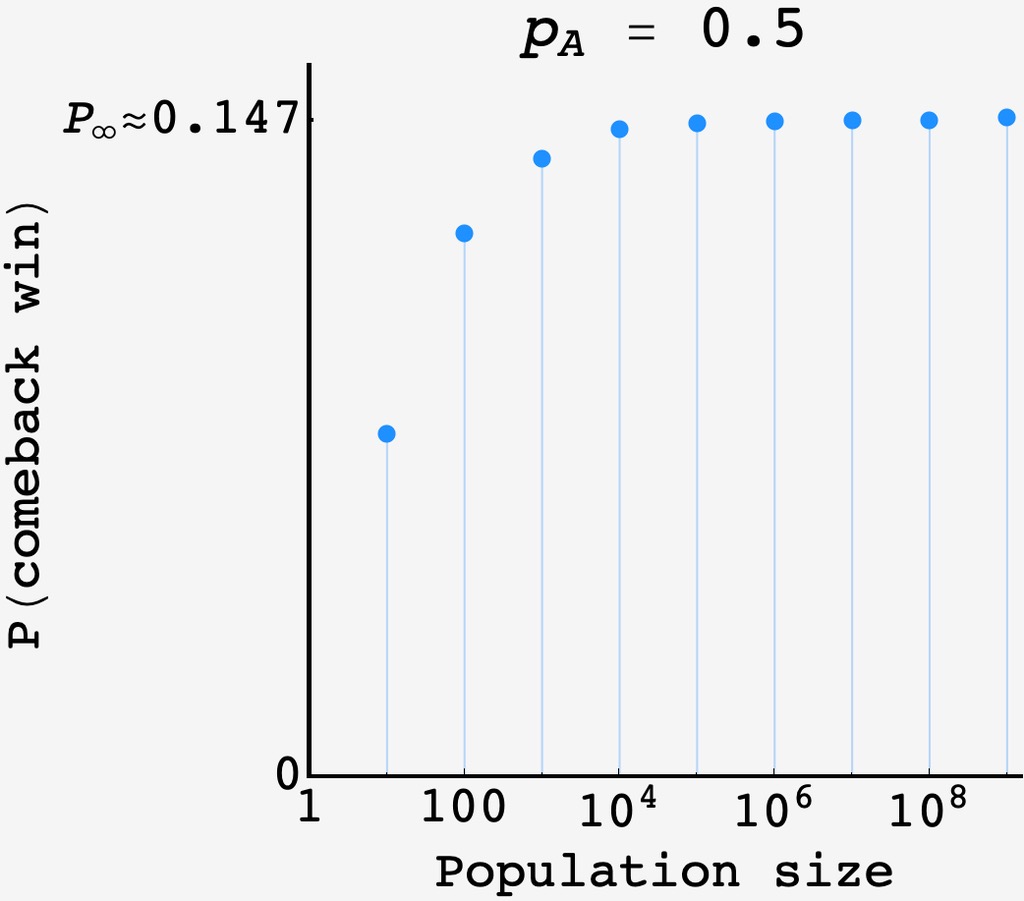

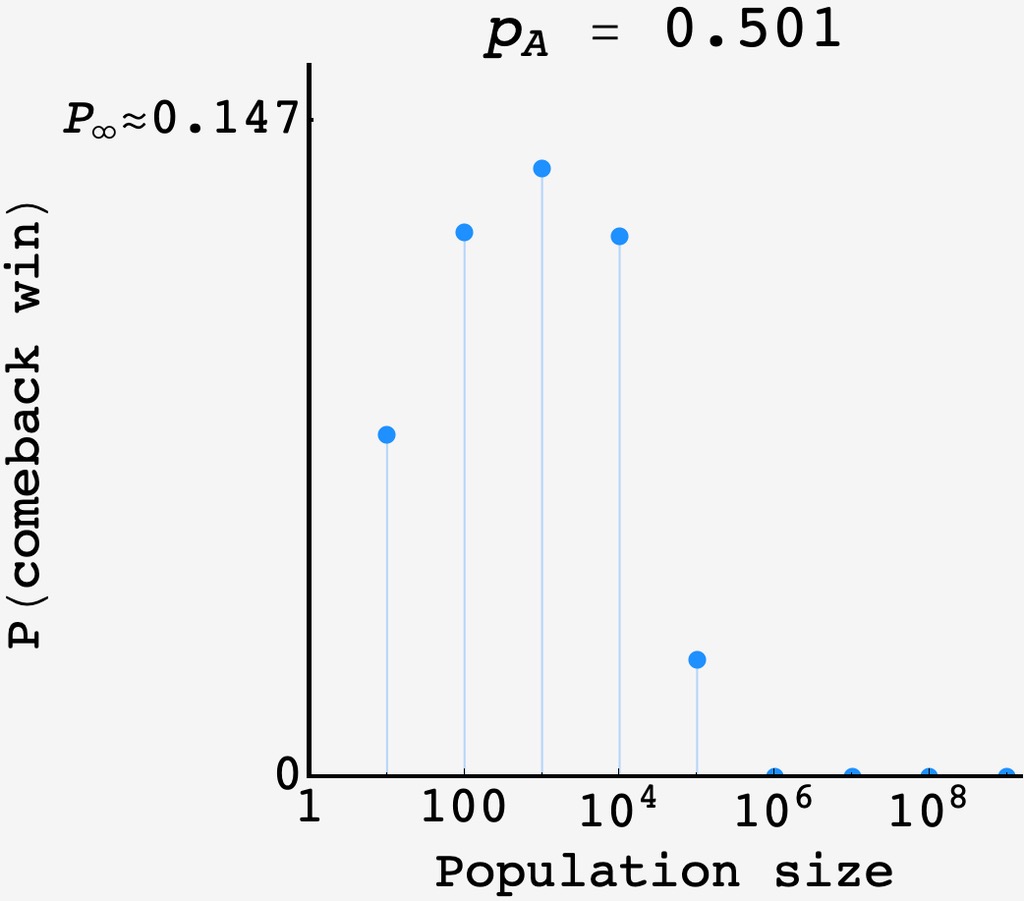

This prediction is confirmed by simulating the system with increasing population size.

When $p=\frac12$ exactly, $P(\text{comeback})$ approaches the prediction asymptotically:

But when $p$ is off by just $1$ part in $1000,$ $P(\text{comeback})$ crashes to zero as the system size eclipses $N=10^5.$

So, the overall result becomes

\[P(\text{comeback}) = \left(\frac12 - \frac{1}{2\pi}\arctan\sqrt{\frac{f}{1-f}}\right)\times\delta_{p,1/2}.\]The plot thickens…