Question: a regular staircase is built from blocks and the blocks in each level are different colors. The staircase can be built in whatever order that’s physically possible. However, whenever you make a choice, the Universal wave function splits so that each staircase actually exists in its own branch of the multiverse. In addition, the surface the stairs are built on is slightly sloped (in all verses), so any placed block slides forward until it hits the wall. How many universes will spawn to accommodate the possibilities for the $4$-level staircase? An $n$-level staircase?

Solution

I got started by building some staircases.

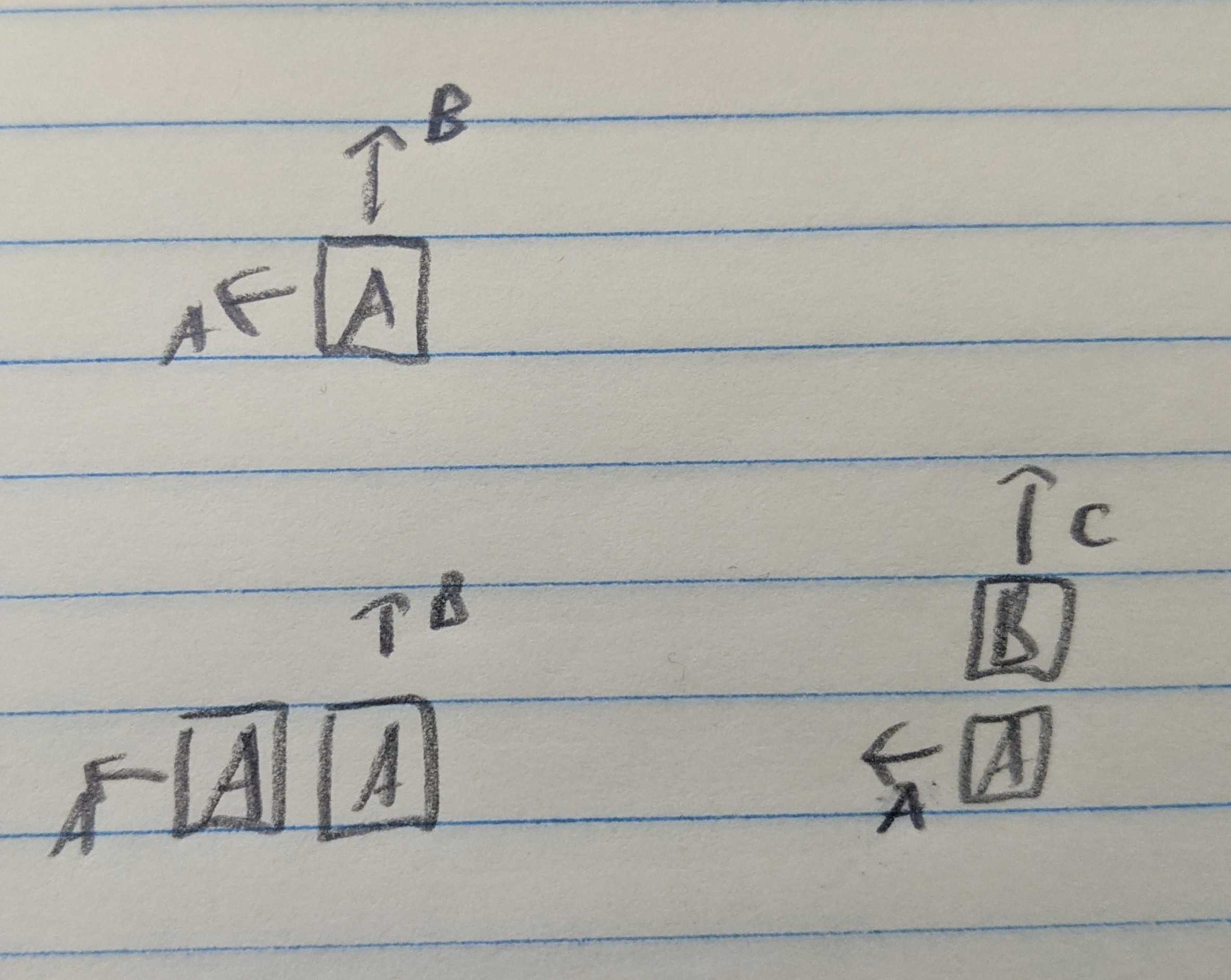

For the two level staircase, there’s no choice for the first block, we have to start with an “A” block, since every other block needs a foundation on which to be placed. Once the first “A” block is placed, we have a choice for what to do second, we can either place the “B” block on top of the first “A” block, or we can place the second “A” block and then place the “B” block last. This makes for a total of $2$ ways to build the $n = 2$ level staircase.

Schematic for Observation $2.$

Moving to the three level staircase, we again need to kick things off with an “A” block. From there we can either place a “B” block (on top of the first “A” block) or we can place another “A” block, extending the first level. In the situation where we placed a “B” block second, we now have the option to place a “C” block, or to place another “A” block.

Some observations

You can carry on like this, but it gets out of control fast. At this point I noticed a couple of patterns.

- we can always place an unplaced “A” block.

- we can place a “B” block if the number of unplaced “A” blocks is equal to or less than the number of placed “B” blocks (and the same condition for “C” compared to “B”).

- if multiple blocks have legal placements, then form a branch for each possibility.

- if we have filled out column, say by placing “A-B-C” in a stack, then the remaining $2$ “A” blocks and $1$ “B” block present the same problem as if we had the $2$-stair problem.

- if we have $1$ block left, then there’s only one way to place it.

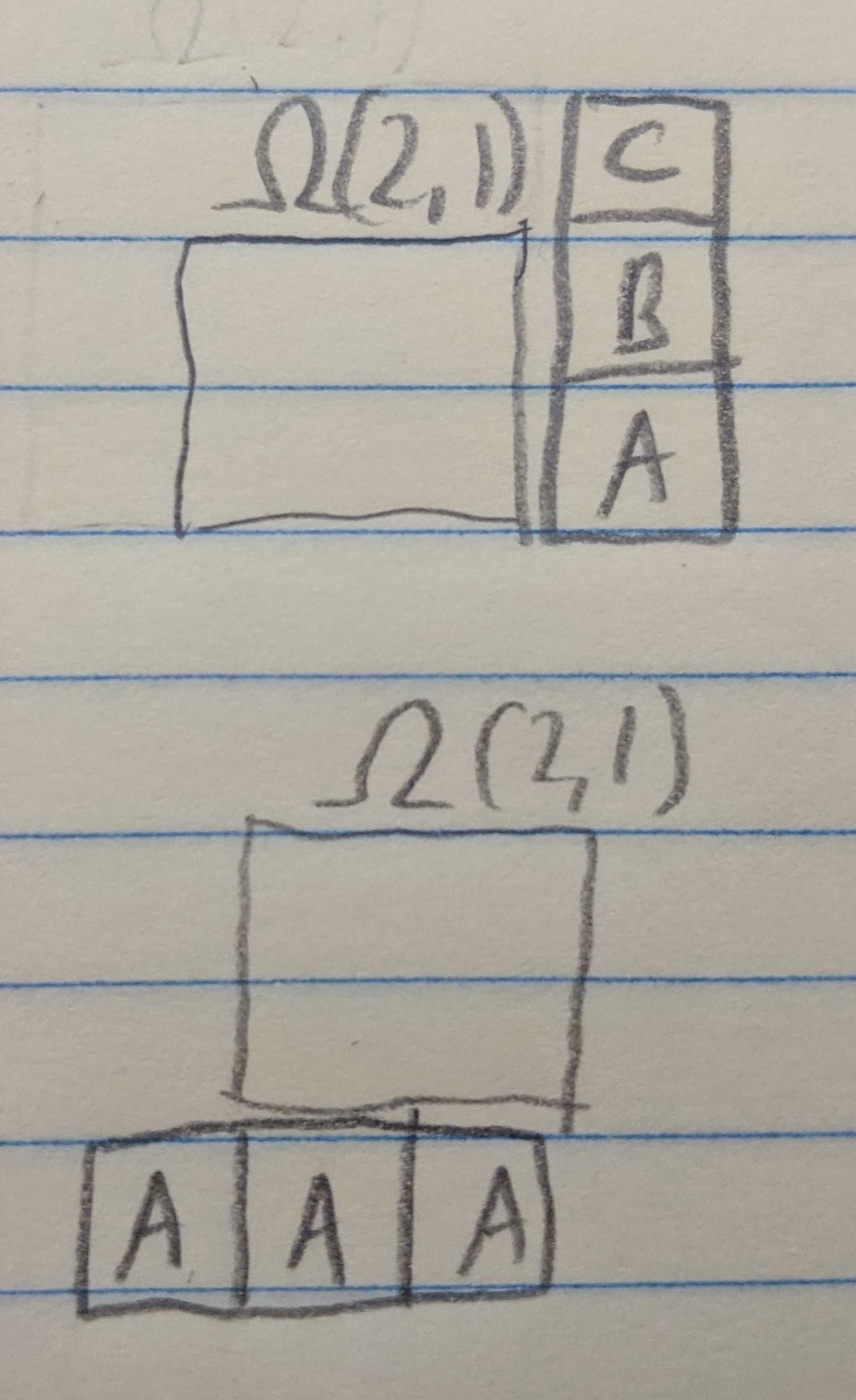

On account of the Observation $3$, I started using a notation in hopes to find a recursion: $\Omega(a,b,c)$ is the number of ways that $a$ remaining “A” blocks, $b$ remaining “B” blocks, and $c$ remaining “C” blocks can be placed in the staircase.

Schematic for the partial recursion of Observation $2.$

Using the notation

Let’s use the notation to recreate the two stairs result, and get a number for the three stairs result.

Two stairs

Starting with $2$ “A” blocks, and $1$ “B” block, we are trying to calculate $\Omega(2,1).$ With no blocks placed, we are obligated to place an “A”, so we get

\[\Omega(2,1) = \Omega(1,1).\]Since $a = b$ we are free to place an “A” or a “B”. According to Observation $2$, this means that

\[\Omega(1,1) = \Omega(1,0) + \Omega(0,1).\]According to Observation $5$, $\Omega(1,0)$ and $\Omega(0,1)$ are both equal to $1.$ Altogether, this shows that $\Omega(2,1) = 2.$

Three stairs

Now let’s do the three stair case, moving a little more quickly this time. We start with $\Omega(3,2,1).$ To start, we’re forced to place an “A,” so

\[\Omega(3,2,1) = \Omega(2,2,1).\]Now, we can place an “A” or a “B,” so we form two branches:

\[\Omega(2,2,1) = \Omega(1,2,1) + \Omega(2,1,1).\]By Observations $1$ and $3,$ we get

\[\begin{align} \Omega(1,2,1) &= \Omega(0,2,1) + \Omega(1,1,1) \\ \Omega(2,1,1) &= \Omega(2,1,0) + \Omega(1,1,1) \end{align}\]By Observation $4,$ we get $\Omega(0,2,1) = \Omega(2,1,0).$ Also by Observation $4,$ these problems are equivalent to the original $2$-level staircase, so $\Omega(2,1,0) = \Omega(0,2,1) = 2.$ Both terms share $\Omega(1,1,1)$ which we carry on calculating.

Since the agruments are equal, $\Omega(1,1,1)$ gives three choices for placement:

\[\Omega(1,1,1) = \Omega(1,1,0) + \Omega(1,0,1) + \Omega(0,1,1).\]Again, each of these has been calculated previously as all are equal to $\Omega(1,1) = 2$ from the two stair problem.

Propagating back up the chain, this shows that $\Omega(1,1,1) = 6,$ $\Omega(2,1,1) = 8,$ $\Omega(1,2,1) = 8,$ and $\Omega(3,2,1) = \Omega(2,2,1) = 16.$

Translating

We can translate from the list of observations into a formal rules. For an arbitrary number of stairs, we have

\[\Omega(a,b,c,\ldots) = \small\begin{cases} 0 & \min(a,b,c,\ldots) < 0 \\ 0 & (b \geq a)\,\mathbf{OR}\, (c \geq b)\, \mathbf{OR}\, \ldots \\ 1 & \left(a+b+c+\ldots\right) = 1 \\ \Omega(a-1,b,c,\ldots) + \Omega(a,b-1,c,\ldots) + \Omega(a,b,c-1,\ldots) + \ldots & \text{otherwise} \end{cases}\]Coding this up (using memoization),

F[a_, b_, c_, d_] := F[a, b, c, d] = (

If[a + b + c + d == 1, Return[1]];

Return[

F[a - 1, b, c, d] If[a > 0, 1, 0]

+ F[a, b - 1, c, d] If[b >= a, 1, 0] If[b > 0, 1, 0]

+ F[a, b, c - 1, d] If[c >= b, 1, 0] If[c > 0, 1, 0]

+ F[a, b, c, d - 1] If[d >= c, 1, 0] If[d > 0, 1, 0]

]

)

we get $\boxed{\Omega(4,3,2,1) = 768},$ all of which can be seen here courtesy of Goh Pi Han.

This code doesn’t extend nicely to bigger staircases, which we can take care of with:

oneAtI[i_, L_] := Table[If[n == i, 1, 0], {n, 1, L}];

f[toPlace_] := f[toPlace] = (

levels = Length[toPlace];

If[Total[lst] == 1, Return[1]];

fsum =

Sum[

f[toPlace - oneAtI[i, levels]]

If[i > 1, If[toPlace[[i]] >= toPlace[[i - 1]], 1, 0], 1]

If[toPlace[[i]] > 0, 1, 0]

, {i, 1, levels}

];

Return[fsum]

)

Exploring some bigger staircases, we find:

\[\begin{array}{|c|c|}\hline N & \Omega \\ \hline 1 & 1 \\ \hline 2 & 2 \\ \hline 3 & 16 \\ \hline 4 & 768 \\ \hline 5 & 292,864 \\ \hline 6 & 1,100,742,656 \\ \hline 7 & 48,608,795,688,960 \\ \hline \end{array}\]Searching the first few terms on the OEIS, this is a known series for the number of ways to build out a triangular Young tableau. A Young tableau is a grid shape where numbers are filled out such that they increase along the rows and up the columns which, if we numbered our blocks according to when they were placed, is the case with our staircases as well. So, this makes sense.

Some very beautiful combinatorics shows the number of ways to build a Young tableau for a grid of any shape is equal to the factorial of the number of grid cells, divided by the product of the number of lesser values that each cell sees in its row and column. In our staircase, this means $(2n+1)$ for the first “A” placed, $(2n-1)$ for the second “A” placed, $(2n-3)$ for the third “A”, and so on down to $1$ for the last “A” placed. Similarly, starting from the left, the “B” blocks see $(2n-1),$ $(2n-3),$ $\ldots$, $1$ lesser values.

All told, these “lesser values seen leftward and upward” yield $n$ powers of $1$, $(n-1)$ powers of $3,$ $(n-2)$ powers of $5,$ and so on, until the $n^\text{th}$ odd number which has a single power.

We can check this for the $n=4$ staircase, where the prediction is

\[\Omega = \dfrac{\left(1+2+3+4\right)!}{1^4\times 3^3\times 5^2\times 7} = 768\]as expected. In general, the number of ways to build the $n$-level staircase is (abusing notation)

\[\boxed{\Omega = \dfrac{\left(1+2+\ldots+n\right)!}{\prod_{i=0}^{n-1} (2i-1)^{n-i}}}.\]