Question: the hometown coin flipping team has staked out a healthy lead, in fact there’s a $\gt 99\%$ chance they bring home the championship (chip). Suddenly, disaster strikes, and they experience a total collapse and lose the game. If the game is a best of $101$ flips, what’s the chance to witness this devastating upset?

Solution

This problem is about devastation — games where our team gets to a point where they have a $99\%$ chance (or greater) to win only to completely blow the lead and lose the game.

Trajectory probabilities

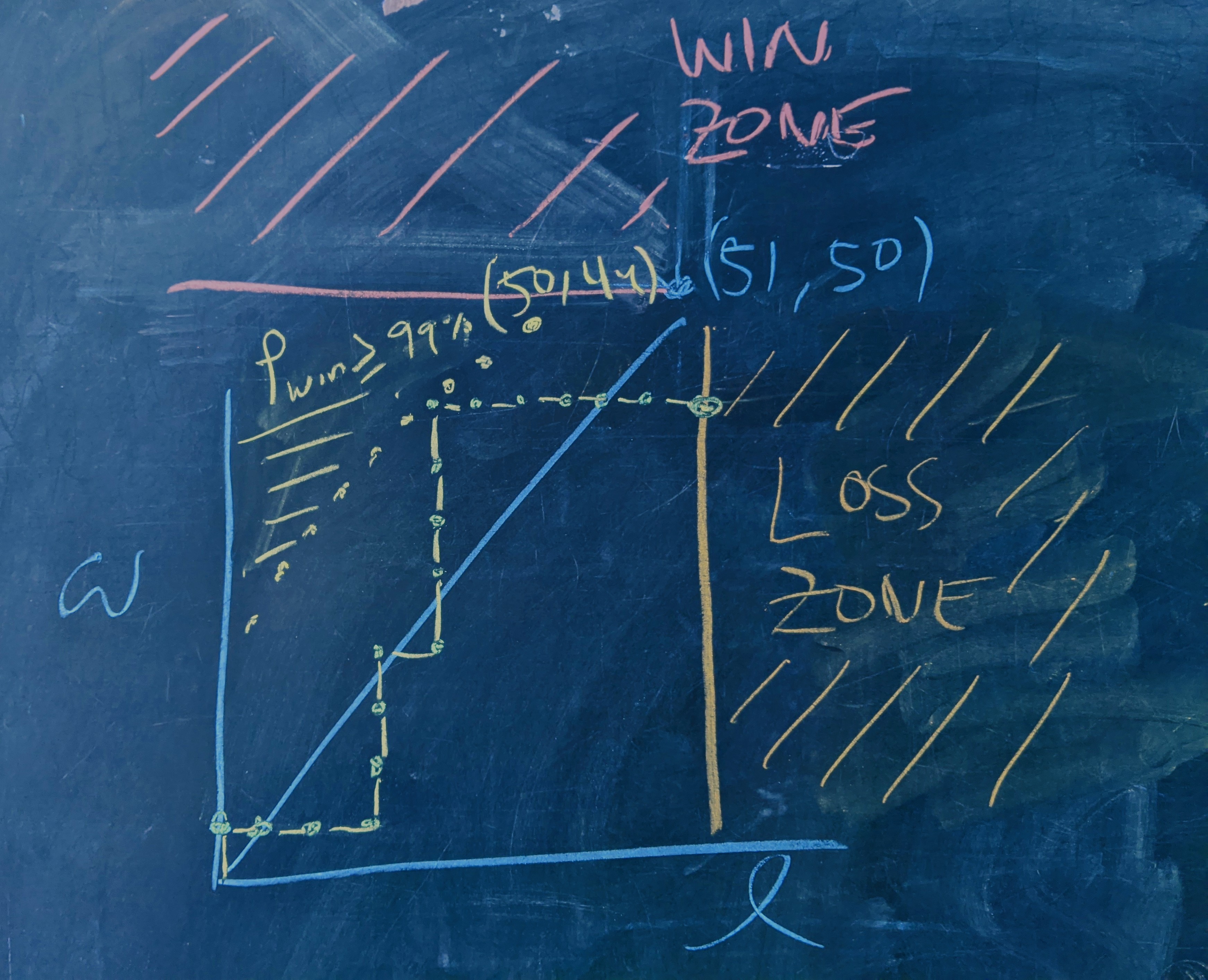

By implication, there are points in the space of scores $(w,\ell)$ where there is a $99\%$ or greater chance for the Birds to maintain their lead and go on to win. If we can find the set of those points, $\mathcal{S},$ then the probability of witnessing a collapse is just

\[P_\text{collapse} = \sum_{S_i\in\mathcal{S}} P(\text{start} \rightarrow S_i)\times P(S_i \rightarrow\text{collapse}).\]Here, $P(S_i\rightarrow\text{collapse})$ is the probability that after reaching the point $S_i$ (with $w \gt \ell$) the Birds go on to lose the game. We don’t care how the Birds makes it from $S_i$ to a loss, any path will do.

$P(\text{start}\rightarrow S_i)$ is the probability that a game makes it to the point $S_i.$ More specifically, it’s the probability that the game makes it to $S_i$ before visiting any other point in $\mathcal{S}$ — if it’s already been to $\mathcal{S}$ we ignore it since we don’t want to double count. The fact that we need to classify trajectories according to which point in $\mathcal{S}$ they visit first makes this quantity tricky to calculate.

The Birds start things off with a lead, then go under, then rocket up to a point in $\mathcal{S}$ before completely blowing the lead and ending up in the $\mathbf{LOSS\, ZONE}.$

From $\mathcal{S}$ to an $L$ — the likelihood of collapse

If we can calculate $P((w,\ell) \rightarrow\text{collapse})$ then we can find the points of $\mathcal{S}$ simply by scanning the grid for points where it is $ \lt 1\%.$

The Birds will lose if they get to $51$ losses. If they’re at the point $(w, \ell)$ then they need to lose $(51 - \ell)$ more games to win. THey can do that in a number of ways. They could lose $(51 - \ell)$ straight games, they could win $1$ game amidst losing $(51 - \ell)$, etc. In fact, they can win as many as $(51 - w - 1)$ more games so long as they lose $(51-\ell)$ of them in the process.

The number of paths the Birds can take that win $w^\prime$ games and lose $\ell^\prime$ games is just $\binom{w^\prime + \ell^\prime}{\ell^\prime}.$ When the game picks up from $(w, \ell),$ the total number of trajectories it can take is $2^{101 - (w + \ell)}.$ So, the total probability of a loss starting at the point $(w, \ell)$ is

\[P_\text{loss}(w,\ell) = \frac{1}{2^{101 - (w + \ell)}} \sum_{\ell^\prime = 51 - \ell}^{101 - (w + \ell)} \binom{100 - (w + \ell)}{\ell^\prime}.\]Coding it up in Python

from scipy.special import comb as binom

def P_to_lose(w, l):

P = 0

# have to lose at least (51 - l) more times

min_losses = 51 - l

max_losses = 101 - (w + l)

for losses in range(min_losses, max_losses + 1):

wins = 101 - (w + l) - losses

P += binom(wins + losses, losses) / 2 ** (101 - (w + l))

return P

we can try it out on some test cases. As expected, this gives $1/2^{51-\ell}$ for the points $\left(50, \ell\right),$ and $5/16$ for $(49, 48).$

Running this over the half grid, it identifies $632$ points for which $P_\text{loss} < 1\%,$ i.e. the points of $\mathcal{S}.$

points = []

for w in range(1, 51):

for l in range(0, w):

if P_to_lose(w, l) <= 0.01:

points.append(tuple([w,l]))

points.append(tuple([l,w]))

But the set is structured such that a boundary points of $\mathcal{S}$ separate its interior from the rest of the $(w,\ell)$ plane. Therefore, only these boundary points can be points of first visitation.

Getting to $\mathcal{S}$

To find the probabilities $P(\text{start}\rightarrow S_i),$ an analytic approach for first visitation is tough since the points of $\mathcal{S}$ change their distance from the line $w=\ell$ over time. To get around this, I deployed $1,000,000$ random walkers on the grid and kept track of the fraction of the time that a point in $\mathcal{S}$ was encountered. As soon as either one such point was encountered, or the line $w + \ell = 101$ was encountered, the run stopped and a new one was started.

First, we make a dictionary to store the probabilities for all the points of $\mathcal{S}:$

point_hits = {}

for _ in points:

point_hits[tuple(_)] = 0

Then we deploy the random walkers:

N = 1_000_000

for _ in range(N):

pt = np.array([0,0])

while sum(pt) < 101:

if random.random() <= 0.5:

pt += [1,0]

else:

pt += [0,1]

if tuple(pt) in points:

point_hits[tuple(pt)] += 1 / N

break

The total probability of arriving in this set is found through

total_P = sum(v for k, v in point_hits.items())

which produces $P(\text{start}\rightarrow \mathcal{S}) \approx 0.304.$

For many points $(w, \ell),$ the first passage probability to $(w, \ell)$ is significantly smaller than the arrival probability given by enumerating the trajectories to it, which is what we can do risk-free for $P(S_i\rightarrow\text{collapse}).$ This indicates that a large fraction of trajectories to points in $\mathcal{S}$ encounter multiple $S_i$.

To find the total probability of witnessing the Birds collapse, we sum over all the points of $\mathcal{S}$ the probability of arriving at point $S_i$ from the origin multiplied by the probability of collapsing from point $S_i:$

P_collapse = 0

for pt in points:

(w, l) = pt

if w < l:

None

else:

P_first_arrival = (point_hits[tuple([w,l])] + point_hits[tuple([l,w])]) / 2

P_collapse += P_first_arrival * P_to_lose(w, l)

P_collapse

which comes to

\[\boxed{P_\text{collapse} \approx 0.0021132670677359183}\]Continous

In Emma Knight’s writeup, she formulates an “inaccurate” analytic approach with a very self-consistent equation for $P_\text{collapse}.$ She starts out, as we do above, by noticing that the probability of collapse is given by the probability of reaching a point in $\mathcal{S}$ multiplied by the probability of proceeding to lose.

Optimistically:

\[P_\text{collapse} = P(\text{start}\rightarrow\mathcal{S})\times P(\mathcal{S}\rightarrow\text{collapse})\]What she then notices is that every single trajectory that ends in a win is, at some point, in the set $\mathcal{S}$ though possibly not until the final flip. So, the total probability of entering the set $\mathcal{S}$ is $1/2$ (all the winning trajectories) plus $P_\text{collapse}$ (the probability of reaching the set $\mathcal{S}$ before going on to lose).

So

\[P(\text{start}\rightarrow\mathcal{S}) = 1/2 + P_\text{collapse},\]making the original equation

\[P_\text{collapse} = \left(1/2 + P_\text{collapse}\right)\times P(\mathcal{S}\rightarrow\text{collapse})\]At this point we run into the issue that, for the discrete case, hardly any of the frontier points of $\mathcal{S}$ have $P(S_i\rightarrow\text{collapse}) = 99/100.$ They all overshoot it by varying degrees. This is why we had to formulate the binomial sum above, to account for the variation in $P(\mathcal{S}\rightarrow\text{collapse}).$

However, Emma’s model is actually a huge success in the continuum limit. In the continuum, there is no guesswork about the value of $P(\mathcal{S}\rightarrow\text{collapse}),$ it’s actually equal to $99\%$ on the nose for the frontier of $\mathcal{S}.$ If we replace $99\%$ with the generic $1-f$ then

\[P_\text{collapse} = \frac{1}{f}\left(1/2 + P_\text{collapse}\right)\]which leads to

\[\boxed{P_\text{collapse} = \frac12 \frac{f}{1-f}}.\]For the case at hand, this predicts a continuum value of $P_\text{collapse} = 1/198.$ For $75\%,$ we get $P_\text{collapse} = 1/6$ and for $65\%$ we get $7/26.$