Question: Mira the baby architect has a tapering post and some rings. If placed alone, each ring will “find its height” and rest there. If a ring with a higher rest height is placed before one with a lower rest height, the higher one will cut the bottom of the post off from ring placement. How many different ways are there to stack a ring tower?

Solution

This solution has two phases:

- Getting the structure of the problem

- Solving the resulting recurrence relation

We’ll get at the structure of the problem in two passes.

Structure

First some notation. If there are $m$ available heights, and $n$ remaining rings, then we say we have an $S(m,n)$ problem. As we’ll see soon, there’s no need to track the identities of the remaining rings.

Imagine we start with the bare post and $5$ rings. As there are $5$ rings and $5$ open heights, we’ll call this the $(5,5)$ stacking problem, or $S(5,5).$

If we drop ring $5$ first, then it will settle to the bottom and we’ll have $4$ rings with $4$ open slots, e.g., $S(4,4).$ We could also stop there, so the total number of cases where ring $5$ is placed first is $S(4,4) + 1.$ We could also drop ring $4$ first, which would settle at its height, and leave us to figure out how to place the $4$ remaining rings at the $3$ remaining heights. Or we could choose to stop there. These contribute $S(3,4) + 1.$ Carrying on, we’d get $S(2,4) + 1$ if we placed ring $3$ first, and $S(1,4)+1$ if we place ring $2$ first. Finally, we have to add $1$ for the case where we skip straight to placing ring $1$ first.

Altogether, this becomes

\[\begin{align} S(5,5) =\ &\overbrace{(1+S(4,4))}^\text{place 5 first} + \overbrace{(1+S(3,4))}^\text{place 4 first} + \\ &\overbrace{(1+S(2,4))}^\text{place 3 first} + \overbrace{(1+S(1,4))}^\text{place 2 first} + \\ &\overbrace{1}^\text{place 1 first} \end{align}\]Or, collecting terms:

\[S(5,5) = 5 + S(1,4) + S(2,4) + S(3,4) + S(4,4).\]This process spawned $S(4,4)$ which is the same kind of problem as the original, just with one less ring and one less height. But it also spawned $S(3,4)$ and $S(2,4),$ and $S(1,4)$ which are new.

We can deal with $S(1,4)$ first. This is the problem of picking $1$ out of $4$ rings to put at $1$ open height. The answer is $4$ and, in general, we can say $S(1,n)=n.$

With $S(3,4),$ two of the four remaining rings can be chosen to sit at height $3$. We’ll then have an $S(2,3)$ problem as well as the option to call it quits and place no further rings. Since we have two choices of which ring to place at height $3$, our choice is arbitrary and both contribute the same number of cases: $2\cdot\left(S(2,3) + 1\right)$. We could also place ring $2$ first which would give us the choice between a $S(1,3)$ problem, or calling it quits.

-cases.jpg)

Diagram of the recursive cases for the $S(3,4)$ problem. The case where we skip straight to placing ring $1$ is not drawn.

In all,

\[S(3,4) = 2\left(S(2,3) + 1\right) + \left(S(1,3) + 1\right) + 1.\]Similarly, the $S(2,4)$ problem give us $3$ choices of ring that could sit at height $2$. After that, we have a $S(1,3)$ problem. We also have the option to stop where we are, so

\[S(2,4) = 3\left(S(1,3) + 1\right) + 1\]These cases contain the general logic: if we don’t place the rings in order then we’ll have extras, giving $n-m+1$ equivalent choices if we want to place a ring at the next available position (height $m$). Otherwise we have a unique choice at the other remaining positions. In all cases, we get a new subproblem with with $(n-1)$ total rings:

\[\begin{align} S(m,n) &= (n-m+1)\left(S(m-1,n-1) + 1\right) + \sum\limits_{i=1}^{m-1}\left(1 + S(i,n-1)\right) + 1 \\ &= n + (n-m)S(m-1,n-1) + \sum\limits_{i=1}^{m-1}S(i,n-1) \end{align}\]Note that it isn’t possible to have more remaining heights than remaining rings, so we take the convention $S(m,n) = 0$ when $m > n.$ Also, our decision to explicitly add $1$ when we “call it quits” implies that $S(0,n)=0.$ We could adopt another convention, but we don’t.

Recursion relation

What I will now relay is the happy endng of the story. Sometime later, I will give a glimpse into the darkness — a tragic episode where I stayed staring into a generating-function-shaped mirage, only to give up all hope of a solution. After a cajoling by Goh Pi Han, I was inspired to give the recurrence one last try. With no further ado, I present the resolution.

At first glance, the recurrence is no joke. It descends levels in two indices, there’s the $n$, and there’s the $(n-m)$ on $S(m-1,n-1),$ and there’s the sum. You just don’t see these every day (maybe you do, but I don’t).

After calculating some of the $S(m,n)$ by hand, we observed that $S(1,3)=3$ and $S(2,3)=7$ are separated by $4,$ $S(3,4)=21$ and $S(2,4)=13$ are separated by $8,$ and $S(4,5)=64$ and $S(3,5)=48$ are separated by $16$. If this generalizes, then we’d have

\[S(n-1,n) - S(n-2,n) = 2^{n-1}.\]At this point I wasn’t expecting much, but it seemed like a small piece that might be provable. Using the recurrence relation,

\[\begin{align} S(n-1,n) - S(n-2,n) &=\left[n + 1\cdot S(n-2,n-1) + \sum\limits_{i=1}^{n-2}S(i,n-1)\right] \\ & -\left[n + 2\cdot S(n-3,n-1) + \sum\limits_{i=1}^{n-3}S(i,n-1)\right] \\ &= 2S(n-2,n-1) + \sum\limits_{i=1}^{n-3}S(i,n-1) \\ & -2S(n-3,n-1) - \sum\limits_{i=1}^{n-3}S(i,n-1) \\ &= 2\cdot\left(S(n-2,n-1) - S(n-3,n-1)\right) \end{align}\]So, the difference between the $(m=n-1)$ and $(m=n-2)$ coefficients with $n$ rings is replaced with twice the difference between the corresponding coefficients in the $n-1$ ring problem. Following this down, we get

\[\begin{align} S(n-1,n) - S(n-2,n) &= 2\cdot\left(S(n-2,n-1) - S(n-3,n-1)\right) \\ &= 2^2\cdot\left(S(n-3,n-2) - S(n-4,n-2)\right) \\ &= 2^3\cdot\left(S(n-4,n-3) - S(n-5,n-3)\right) \\ &= \cdots \\ &= 2^{n-2}\cdot\left(S(1,2)-S(0,2)\right) \\ &= 2^{n-1} \end{align}\]Small miracle, or sneak preview? What about $S(n-2,n) - S(n-3,n)$? Applying the same approach yields

\[S(n-2,n) - S(n-3,n) = 3\cdot\left(S(n-3,n-2) - S(n-4,n-2)\right)\]which recurses $n-3$ times down to $3^{n-3}\cdot\left(S(1,3) - S(0,3)\right) = 3^{n-2}.$

Telescope

And thus, the rest flowed down like a waterfall. Carrying on in this way can get all the pairwise differences so that

\[\begin{array}{|c|c|} \hline \text{Differences} & \text{Values} \\ \hline S(n,n) - S(n-1,n) & 1^n \\ S(n-1,n) - S(n-2,n) & 2^{n-1} \\ S(n-2,n) - S(n-3,n) & 3^{n-2} \\ \ldots & \ldots \\ S(3,n) - S(2,n) & \left(n-2\right)^3 \\ S(2,n) - S(1,n) & \left(n-1\right)^2 \\ S(1,n) - S(0,n) & n^1 \\ \hline \end{array}\]But these are not mere amusements. Nay, the sum of these differences telescopes to the $S(n,n)$ coefficient itself. Adding them up, like a zipper pulled tight in the dead of winter, the number of ways there are for Mira to stack her $n$ rings filters down to:

\[\begin{align} S(n,n) &= \sum\limits_{i=1}^n \left[S(i,n) - S(i-1,n)\right] \\ &= \sum\limits_{i=1}^n i^{n-i+1} \\ &= 1^n + 2^{n-1} + 3^{n-2} + \ldots + (n-2)^3 + (n-1)^2 + n^1 \\ \end{align}\]Magical!

For the case at hand, $S(5,5) = 1^5 + 2^4 + 3^3 + 4^2 + 5^1 = 65.$

Program

We can confirm this divine form by evaluating the recursion on the computer. Setting up the recursive function with memoization in Mathematica, we have

stack[1, n_] := n;

stack[m_, n_] :=

stack[m, n] =

n

+ (n - m) stack[m - 1, n - 1]

+ Sum[stack[i, n - 1], {i, 1, m - 1}];

The first few $S(n,n)$ are

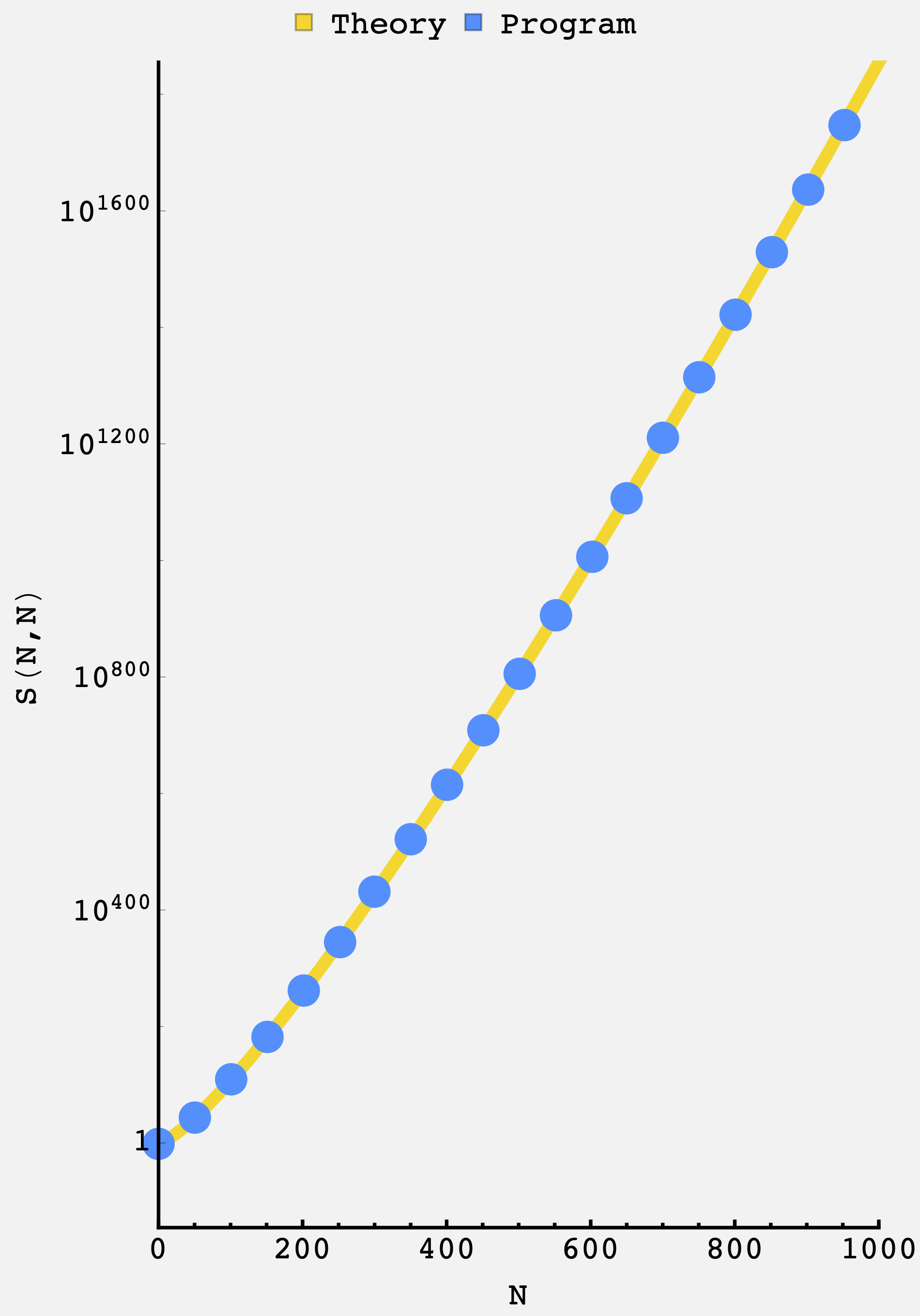

\[\begin{array}{|c|c|} \hline \text{Number of rings} & \text{Distinct stacks} \\ \hline 2 & 3 \\ 3 & 8 \\ 4 & 22 \\ 5 & 65 \\ 6 & 209 \\ 7 & 732 \\ 8 & 2780 \\ 9 & 11377 \\ 10 & 49863 \\ 20 & 2282779990494 \\ 30 & 3939676100069476203757 \\ 50 & 11116503790285362556379694594201865562266651 \\ \hline \end{array}\]The recursion with memoization is quite fast, dispensing with the $100$ ring case in $\approx 170\text{ ms}.$ Plotting the analytical result and the computation up to $N=1000$, we get

Pretty good.