Question: A bacterial colony starts from a single cell that has a probability $\gamma$ of splitting into $2$ and a probability $\left(1-\gamma\right)$ of lysing, as do all of its descendants.

The strain in question is Riddlerium classicum, about which not much is known apart from its cataclysmic reproductive viability, $\gamma = 80\%$ (real bacteria are far more successful, Fig 4 in Robust Growth of Escherichia coli).

What’s the probability that the colony is blessed with everlasting propagation? (i.e. the population never crashes to zero)

Solution

Before answering the main question, there’s the issue of when the colony will become viable in the first place (nonzero probability to be everlasting, $P_\infty > 0$).

The basic insight is that we need the expected number of cells in the next generation to be greater than $1$. In that case, the average outcome after one generation is that we have a solitary cell with the same existential crisis on its hands.

So, if $\gamma < 1/2,$ we should expect $P_\infty = 0.$

Colony flourishing

What if we want to go beyond the prayer of survival — how big does $\gamma$ need to be to push $P_\infty$ to whatever level we like? At first glance, it seems like this could turn into a nested labyrinth of tracking the outcome for each branch of the lineage.

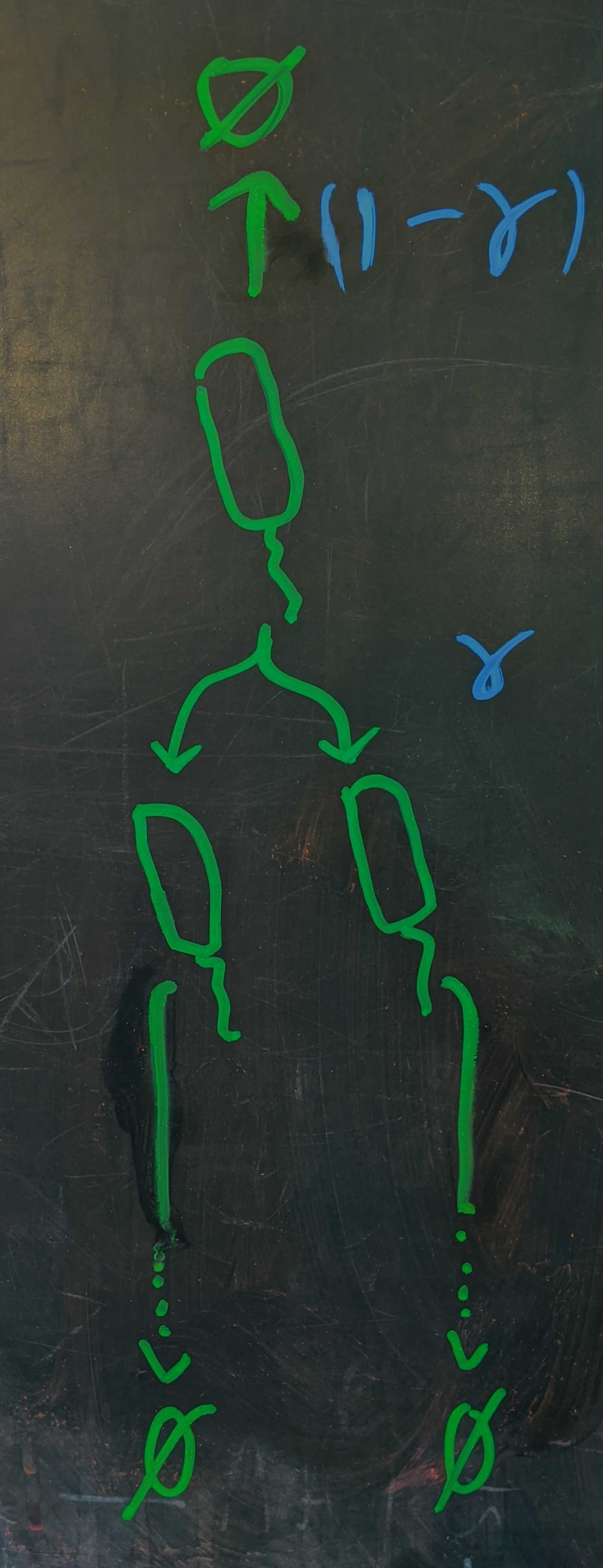

However, each cell has the same prospects. So the probability that the first cell leads to an everlasting colony is equal to the probability that either of its children leads to an everlasting colony.

Each cell can either lyse with probability $\left(1-\gamma\right)$ or reproduce with probability $\gamma$.

Symmetrically, the probability that the first cell has a finite lineage is equal to the probability that it dies plus the probability that it reproduces but both of its children have finite lineages:

\[P(\text{die off}) = P(\text{lyse}) + P(\text{doesn't lyse but both offspring lineages die off}),\]which is

\[P_\text{die} = (1-\gamma) + \gamma P_\text{die}^2.\]This can be solved with the quadratic formula but, if we divide by $P_\text{die}$:

\[1 = \frac{(1-\gamma)}{P_\text{die}} + \gamma P_\text{die}\]it’s a little easier to see that $P_\text{die} = \min\left(1, \left(1-\gamma\right)/\gamma\right).$

A colony either collapses or it doesn’t, so

\[\boxed{\begin{align} P_\infty = 1 - P_\text{die} &= 1-\min\left(1, \frac{1-\gamma}{\gamma}\right) \\ &= 1+\max\left(-1, \frac{\gamma-1}{\gamma}\right) \\ &= \max\left(0, \frac{2\gamma - 1}{\gamma}\right) \\ \end{align}}\]As we anticipated, there’s no chance of an everlasting colony when $\gamma < 1/2.$ And when cells are everlasting, so is the colony: $P_\infty(\gamma = 1) = 1.$

So, what happens?

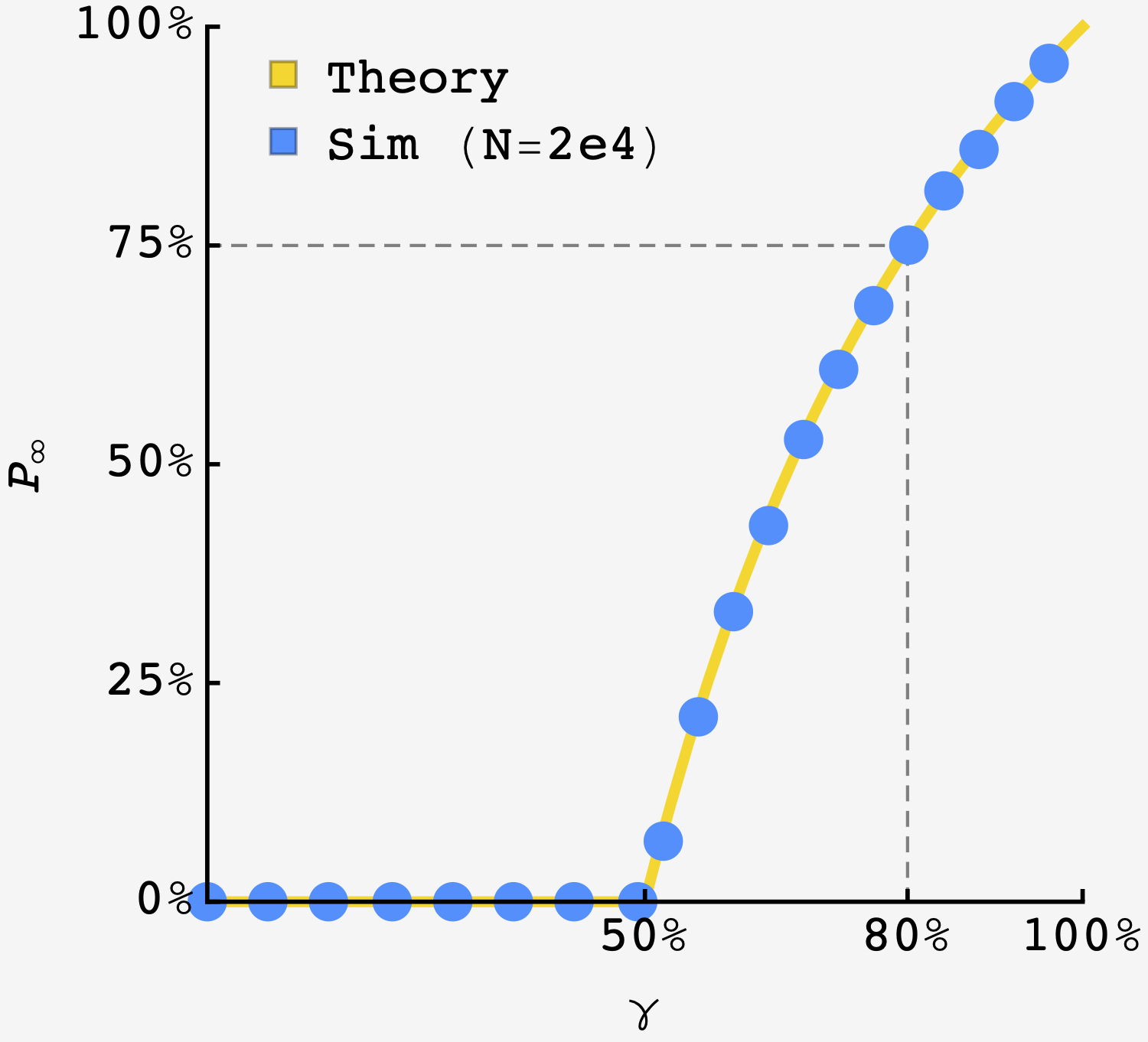

The colony from the problem has $\gamma = 0.8,$ so we expect that $P_\infty = \left(2\times0.8 - 1\right)/0.8 = 75\%.$ The simulation is straightforward, and confirms that $P_\infty(\gamma = 80\%) = 75\%$.

Simulating near the threshold is tricky because more trajectories will be on the fence between colony collapse and making it to the pantheon of everlasting colonies.

If we cut the simulation off too early, e.g. by introducing a cutoff that’s too high, then it will bias our estimate of $P_\infty$ to be too low (some colonies will be diddling under the threshold, before escaping). Likewise, if we introduce a low cutoff, it will look like there are everlasting colonies before the threshold.

To get around this, we can use a high cutoff, but run all colonies until they either hit the cutoff or crash to zero. This would also allow us to measure the false positive rate.

import random

import numpy as np

cutoff = 1000

def conduct_experiment(gamma, start_count):

cell_count = start_count

# For 20 generations of growth

for round in range(20):

# For each cell, double with probability gamma,

# lyse with probability (1 - gamma)

new_cells = sum(

(2 if random.random() < gamma else 0)

for cell in range(cell_count)

)

# Update the cell count

cell_count = new_cells

# If cell_count is bigger than cutoff, return cell_count.

if cell_count > cutoff:

return(cell_count)

# If it's 0 or less, return 0.

elif cell_count <= 0:

return(0)

# Otherwise, keep running.

else:

return(conduct_experiment(gamma, cell_count))

gamma_values = np.arange(0, 1, 0.02)

Ps = []

for gamma in gamma_values:

# Conduct 20000 experiments for each value of gamma

experiments = [conduct_experiment(gamma, 1) for _ in range(20000)]

# Calculate Psurvive and accumulate

Psurvive = np.mean([(1 if expt > 0 else 0) for expt in experiments])

Ps.append(Psurvive)

Using the code above, we get good agreement with the calculation:

Theoretical curve in gold overlaid by results of simulation ($N=2\times 10^4$ per point). The dotted lines show the case of the original problem.