Question: In one of the greatest disasters in the history of collective planning, all 330M residents of the U.S. join the same Zoom call by picking two random times between 8:00 and 9:00. They dial in at the earlier time and hang up at the later time. What is the probability that there is at least one person who is on for some portion of everyone else’s call, a so-called Superzoomer? Further, what is the chance of there being two Superzoomers on the same call?

Solution

Insights

Under the surface fact that the zoom start and end times are random between 8:00 and 9:00 is the fact that they impose an order. The spacing between consecutive points can be scaled however we like — but each ordering of the points has the same set of possible spacings. Finally, if we reassigned the labels of the points at random then we’d have another valid call, so all orders are equally likely.

In sum, the spacings don’t affect the problem, and all possible call schedules are equally probable.

If a Superzoomer exists they have to call in before the first person hangs up and they can’t hang up until the last person starts. This means that they have one of the following relationships with every other person on the call:

- Superzoomer calls in before them and hangs up after them

- Superzoomer calls in before them and hangs up before them

- Superzoomer calls in after them and hangs up after them

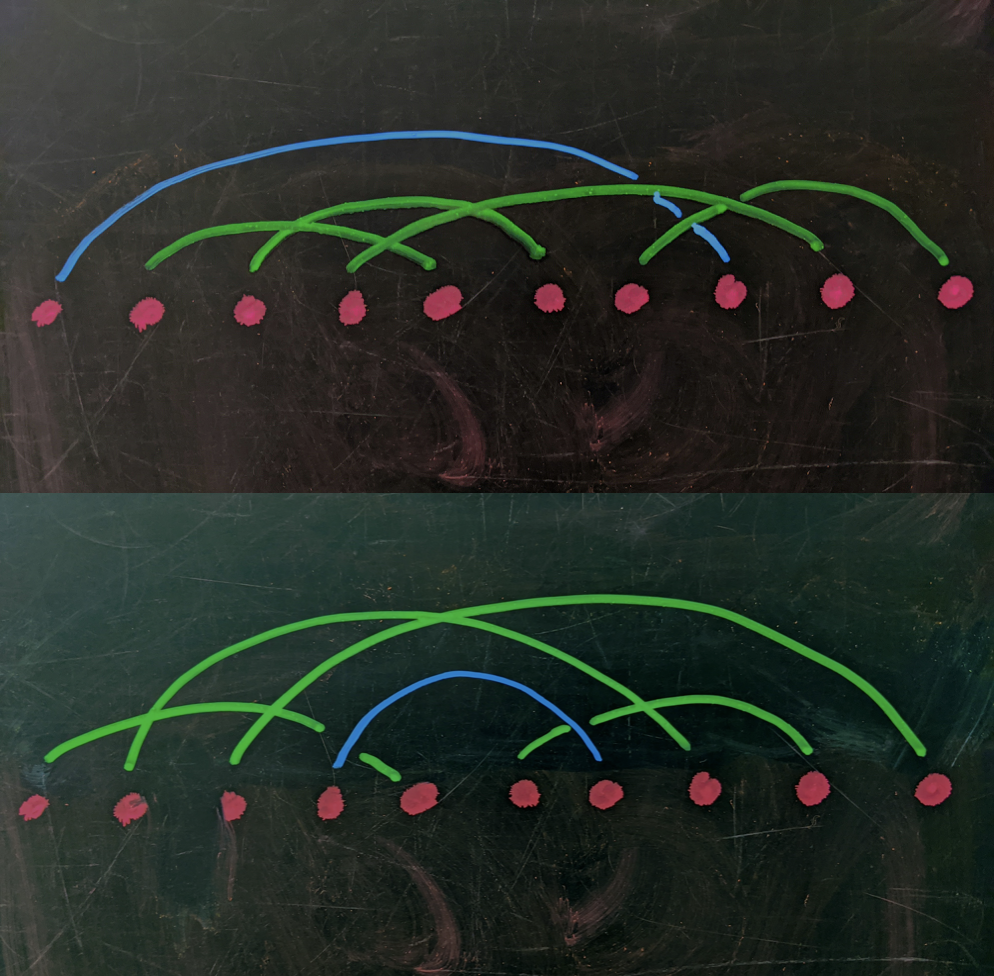

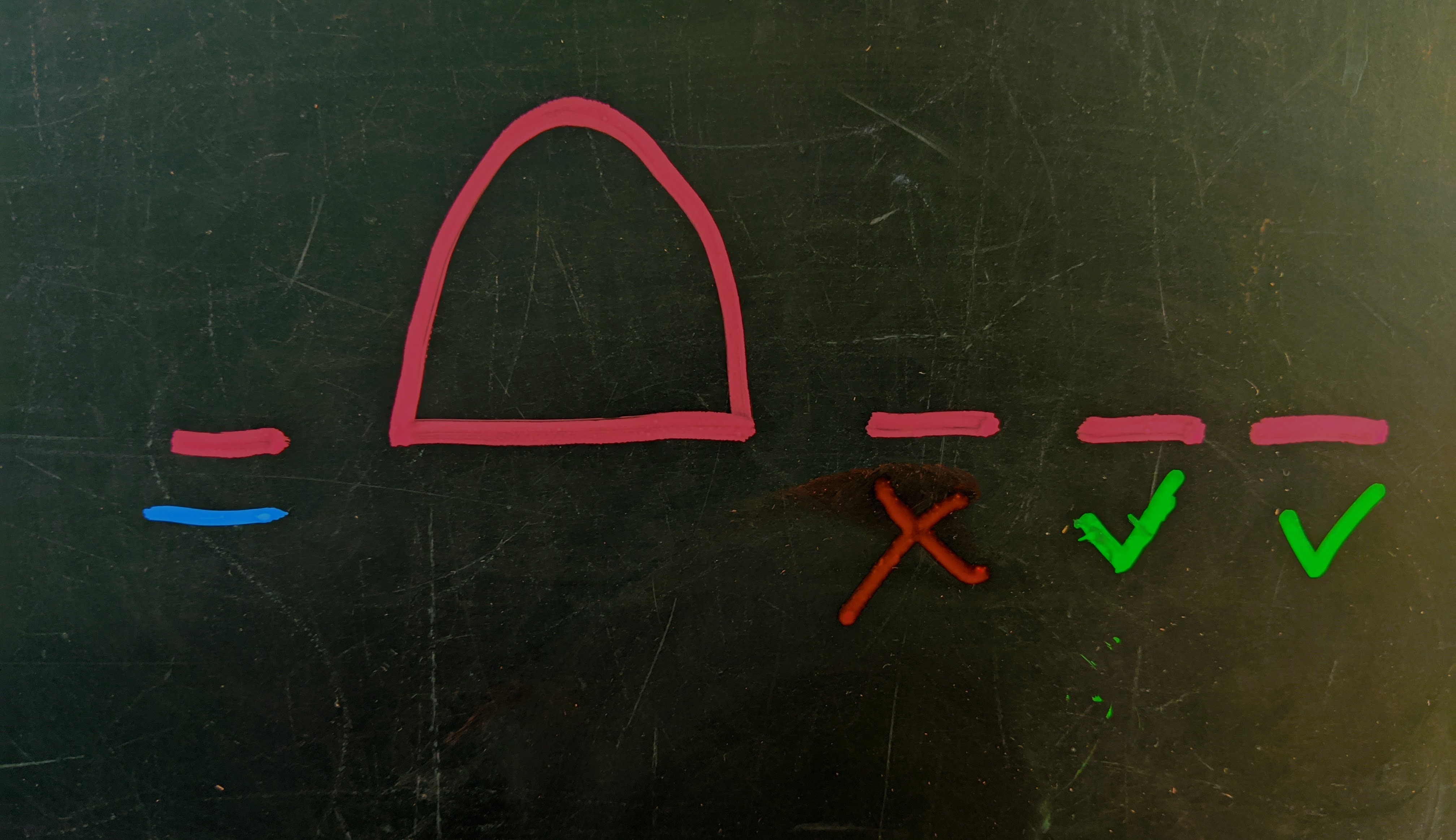

Some possible Superzoomers look like this:

Two exemplary Superzoomers. In the top row we have a Superzoomer with long span, they get on the call first and hang up as soon as the last person calls in. The bottom row shows that a Superzoomer doesn’t necessarily need to be on the call for long. Note that both rows have multiple Superzoomers beyond the one highlighted in blue.

Walking through the back door

Thinking about the forward problem got us very little — we couldn’t see a recursion and we couldn’t organize the combinatorics. This got us thinking, what would it take to dismantle a Superzoomer, e.g., what is the minimal surgery we’d have to do to erase a Superzoomer?

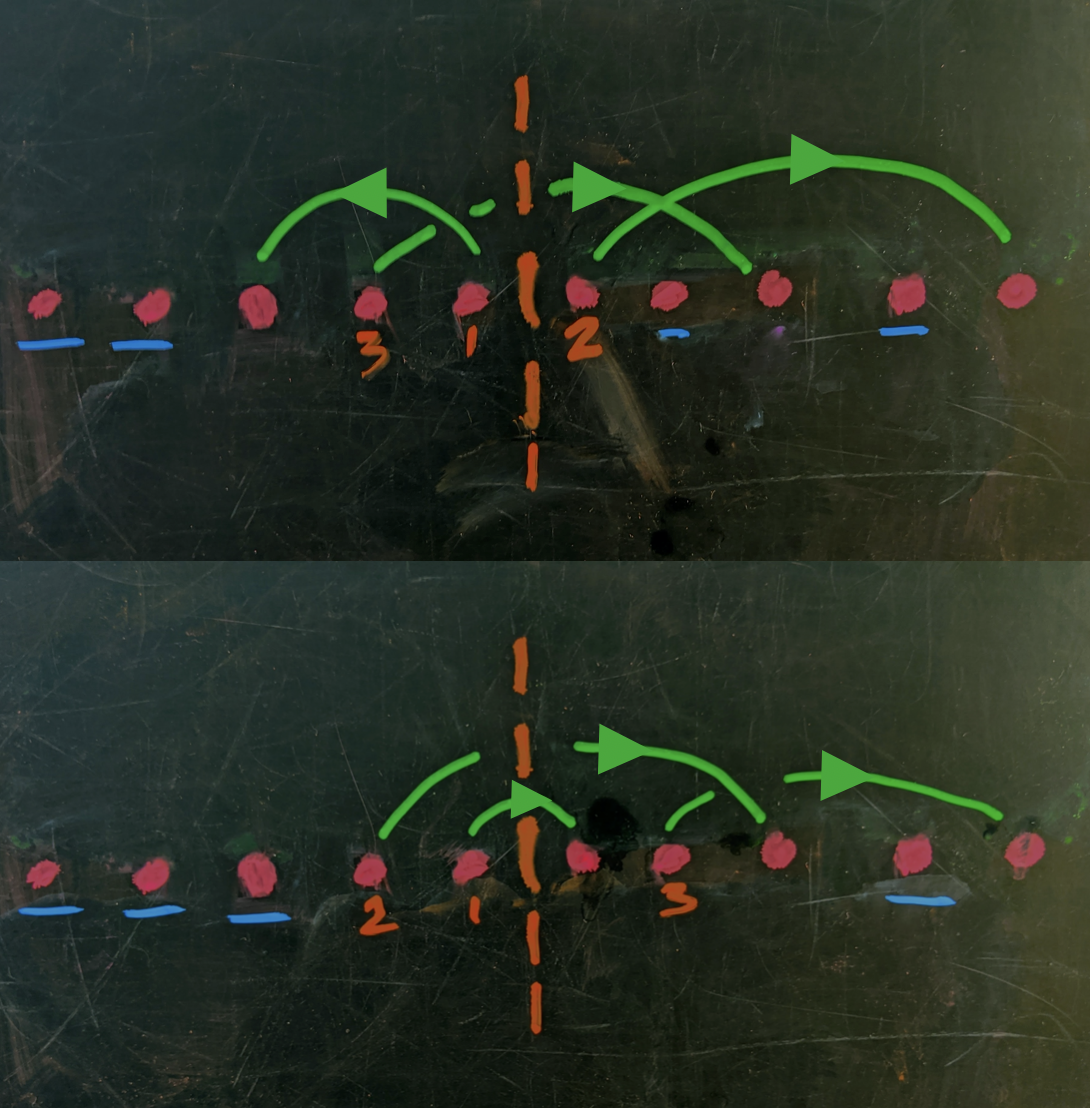

Necessarily, we have to snip the edge of the Superzoomer. But if that’s all we do, we can only reconnect that edge. So we have to cut another edge. If you do this enough times you start to see that it’s always possible to pick the two edges to cut. Moreover, when you reconnect those edges, there are $3$ possible pairings, and $2$ of them make a Superzoomer.

Similarly, if you start with a call schedule that has no Superzoomer, you can trivially create one. Pick two slots such that if they were connected, they’d make a Superzoomer, connect them (making the Superzoomer), and then connect their former connected slots to form a new pair.

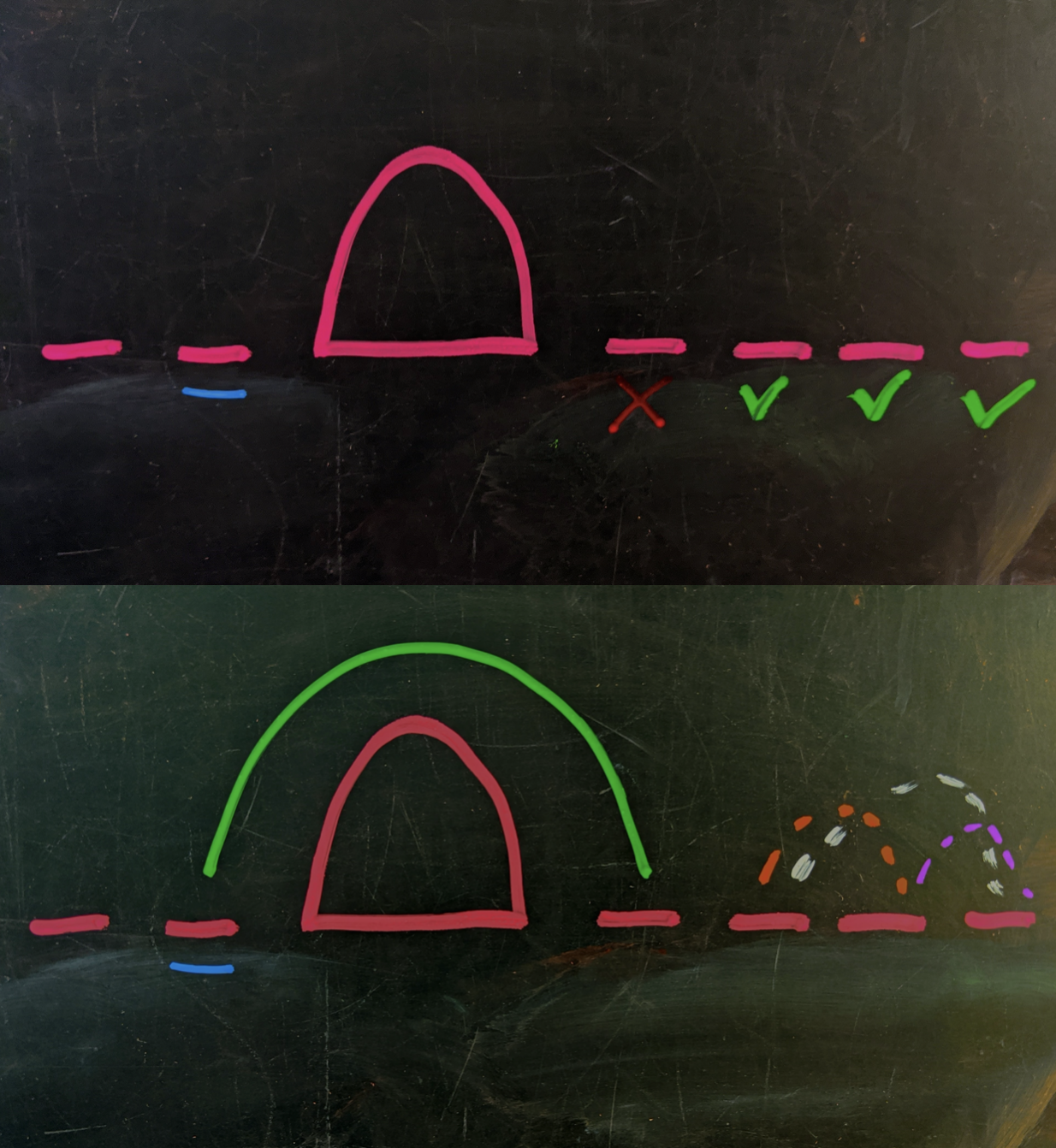

Superzoomer rises Two edges are targeted for removal, then a long two of the open slots are used to make a Superzoomer (who starts before the first person hangs up, and hangs up after the last person calls in). The remaining two edges are connected as well. In this case, both new callers are superzoomers.

Keeping on with this game, you can do the same with $2$ Superzoomers by cutting $3$ edges, with $3$ Superzoomers by cutting $4$ edges, and so on.

This is an exhilarating realization, but is it a mirage?

Suppose these surgeries are always possible: aren’t we cherry picking the points, spoiling the chance that this has anything to do with organically formed call schedules?

No. Every call schedule is equally likely, and it doesn’t matter whether we set a particular caller’s interval first or last.

But how do we pick the edges for surgery?

The essential insight is that the Superzoomer needs to span, at a minimum, $1$ call endpoint (call-in or hang-up) for $(n-1)$ unique callers. If there are more endpoints, which there probably are, it means that some callers started and ended within the Superzoomer’s calling window. So, the condition for forming a Superzoomer is a contiguous stretch of points that contain at least a call-in or a hang-up from $(n-1)$ distinct callers, with empty slots on either side.

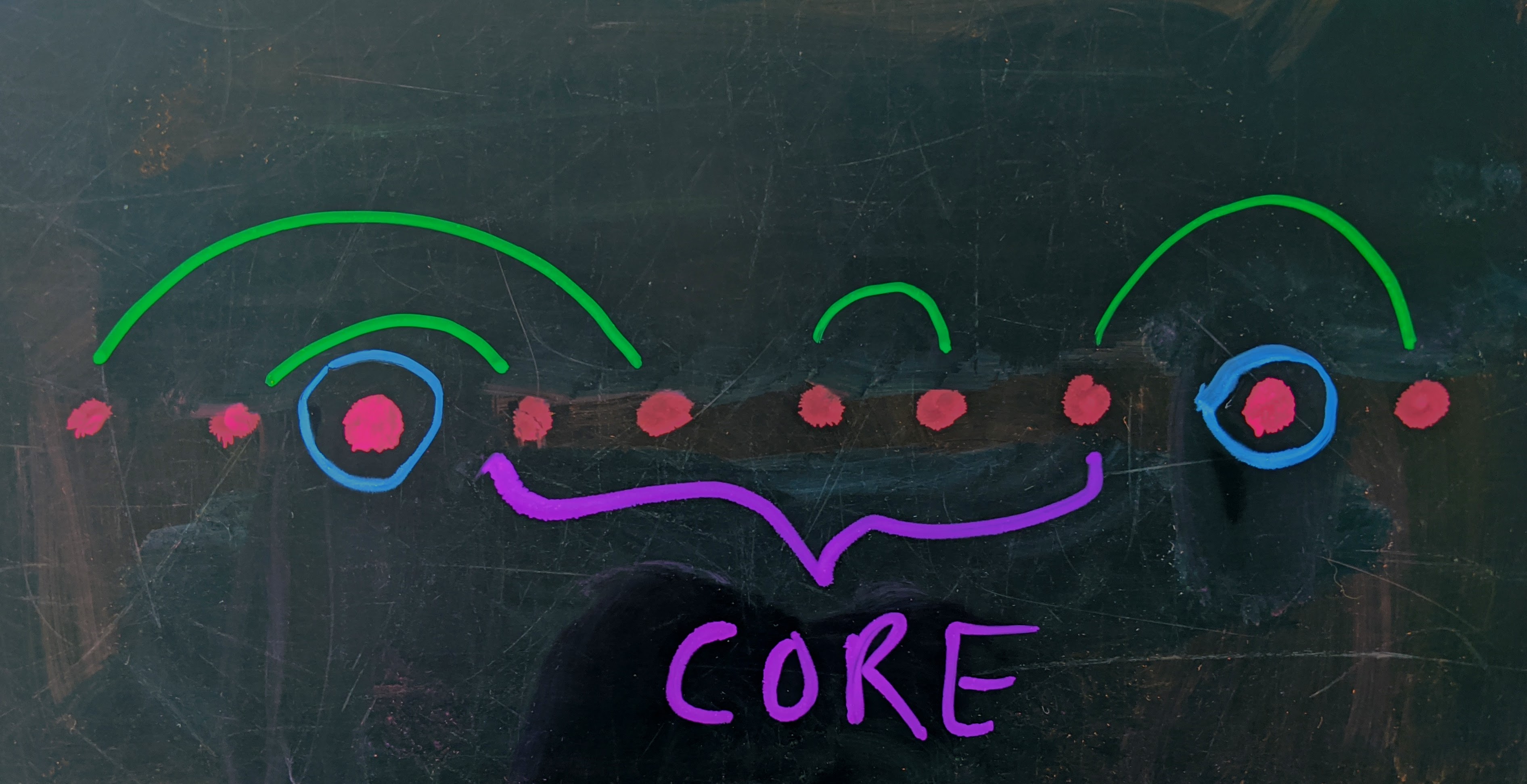

Common Core This core contains at least one terminus for each of the $(n-1)$ callers whose times have already been picked. On either side of the core are open slots.

Notice that the zone of contiguous points can be anywhere along the line, but has to contain the middle point (the zone contains at least $(n - 1)$ points, and the earliest it can end is at position $1 + (n - 1) = n$):

Early to bed, and early to rise The earliest possible Superzoomer is the one who is first to join, leaves right after the last person joins, and noone else hangs up in between..

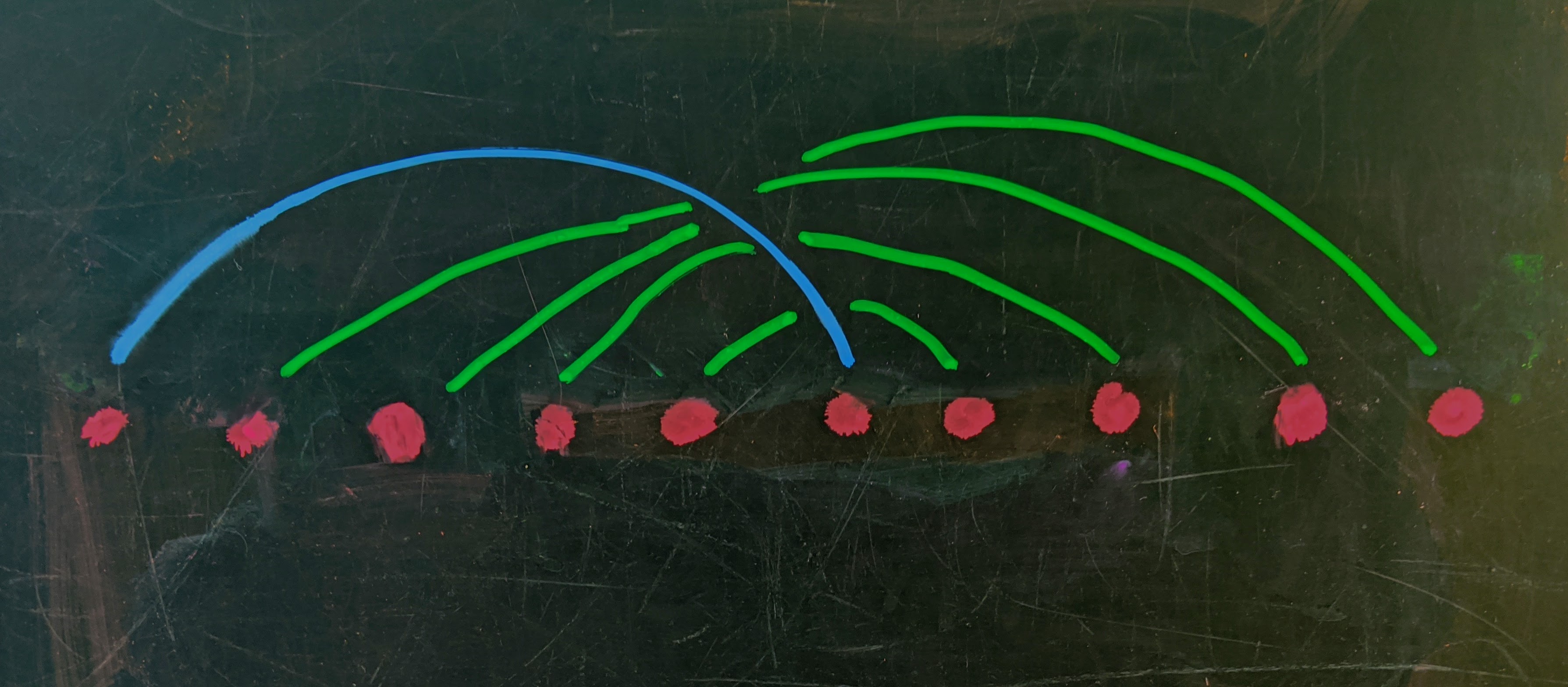

Start at one of the center slots and pick another at random. This is our first calling interval. Our goal is A. to build up a core of lone call-ins, lone hang-ups, or paired call-in/hang-ups, and B. to leave empty slots on either side.

The trouble is, depending on where our next slot leads, we could start to build up an imbalance, e.g. so that the holes are only on one side. For instance, our first slot connects to another slot on the left, so we have $2$ points on the left and $0$ on the right. If we pick our next slot to the left of the first, and it connects to a point on the left, then we have $4$ on the left and $0$ on the right. Clearly, this can result in a situation where we’re ready for our $2$ surgery edges. and they’re both on one side of the core.

Happily, this is easy to avoid. If the first slot connects to a point on the left, then make the next slot the one directly to the right of the first, if this connects to a point on the right, then the imbalance will become zero. If it connects to a point on the left, it will simply maintain the current imbalance. So, if we follow this rule, we can ensure that we always end up with a $(3,1)$ or $(2,2)$ balance of open slots when we’re ready for surgery.

A tale of two cores Two possible constructions of the core — one leading to an imbalanced distribution of the $4$ remaining calling slots about the core, and one balanced.

By construction, the empty slots we have when we’re ready for the surgery edges are always on either side of the core, since we are obsessively picking new slots exactly adjacent to the last slot we picked. So, the core contains one or both endpoints for every other of the $(n - 2)$ callers.

If we have a $(3,1)$ balance, the potential pairings are like this, and $2$ of the $3$ form a Superzoomer.

Decisions decisions Since there is only $1$ open slot on the left, and there are $3$ on the right, $2$ of the slots on the right will endpoints for the same caller. If we join the lonesome empty slot to the right empty slot on the right, then that caller won’t overlap with the caller formed by pairing the two rightmost slots. So, the core-spanning arc cannot land in the first slot on the right.

If we have a $(2,2)$ balance, then unless we pair the ones that are on the same side of the core, we’ll get a Superzoomer, again $2$ out of $3$.

One Superzoomer is never enough.

Like we said in the hands-on feel good section, a surgery to make two Superzoomer means snipping $3$ edges. So, stop the core assembly when there are $6$ empty slots. Again, since we make sure to balance the holes, we can either have $(2,4)$ or $(3,3)$.

If we have $(2,4)$ then we’re going to be immediately forced into three distinct $(2,2)$ scenarios. The simple reason is that two of the slots on the right of the core have to form their own one-sided pair. If we pair the first slot (underlined blue) with the left-most point on the right, it means that this will not overlap with the one-sided pair, ruling the caller out from being a second Superzoomer. So, we have $3$ ways to pick the destination for the $1^\text{st}$ point, which leaves us with a balanced $(2,2)$ experience, which has $2$ ways of producing a Superzoomer. In all, there are $3\cdot 2$ ways to pick them.

One more time We can’t pair the underlined blue slot with the first open slot on the right because the resulting call wouldn’t intersect the path made by thetwo leftover points on the right side.

In the balanced $(3,3)$ case it’s clear that we have $3\cdot 2$ ways to pair them (moreover, a few of the scenarios result in $3$ Superzoomers).

Let’s have $s$ Superzoomers

When there are an equal number of open slots on either side we immediately get $(s+1)!$ ways to pair them up.

In the case when they’re off by $2$, one side has $(s-1)$ open slots and the other side has $(s+1)$ of them. There are $(s+1)$ choices for how to pair off the one-sided pair (on the side with $(s+1)$ open slots), followed by $s!$ ways to pair up the remaining $2s$ endpoints that cross the core.

The pairing choices are made randomly of course, and there are \((2s+1)(2s-1)(2s-3)\cdots 3\cdot 1 = (2s+1)!!\) total ways to pair off a collection of $2(s+1)$ points (e.g. including the core-crossing Superzoomer arcs and not, as well as the cases that don’t meet our Superzoom needs).

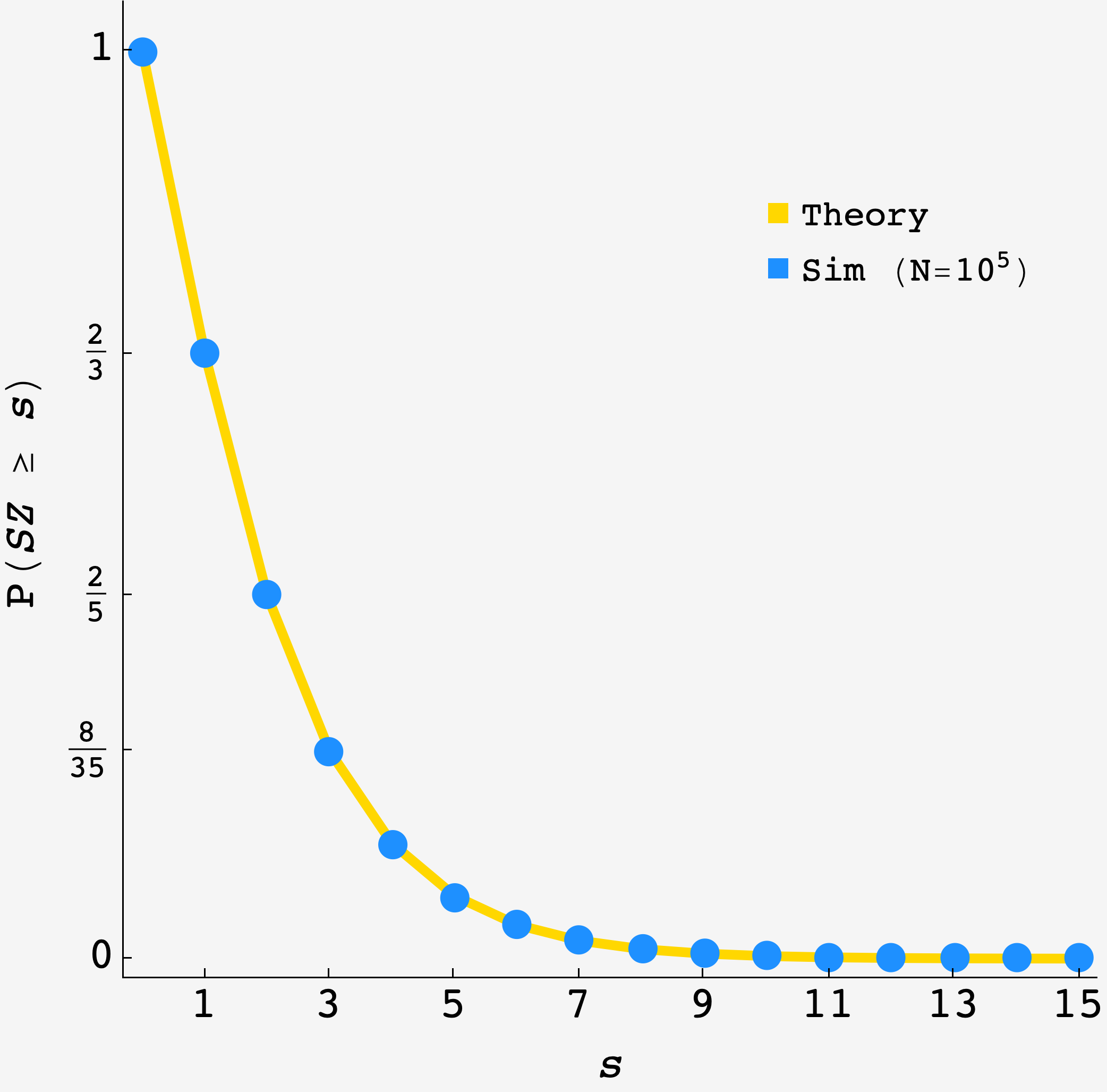

So, the probability of finding $s$ Superzoomers (or more) is

\[P(SZ \geq s) = \dfrac{(s+1)!}{(2s+1)!!}.\]Which matches the simulation

import numpy as np

def round():

people = [];

max_start = 0;

min_end = 1;

for i in range (1000):

x, y = np.random.random(), np.random.random()

temp_start = min(x,y)

temp_end = max(x,y)

if temp_start > max_start:

max_start = temp_start

if temp_end < min_end:

min_end = temp_end

people.append([temp_start, temp_end])

successes=0

for person in people:

if person[0] <= min_end and person[1] >= max_start:

successes += 1

return successes

data = np.unique([round() for i in range(10000)], return_counts=True)