Question: You can make 100 coin flips with either of two coins, Coin A worth $\pm1,$ and Coin B worth $\pm2.$ You survive if you end up with a positive score. How should you flip the coins to maximize your chances?

Solution

The first thing to notice is that, in isolation, the coins have the same outcomes. Coin B’s distribution is just twice as wide as Coin A’s.

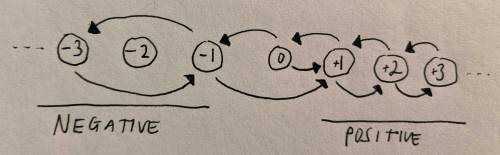

If we imagine the game score as a line, then position $0$ is “neutral” territory, positions $1$ to $100$ are “positive” territory and positions $-100$ to $-1$ are “negative” territory. Coin A moves the score by $\pm 1$ while Coin B moves it by $\pm 2.$

One plausible strategy to bias positive outcomes is to use Coin B until a trajectory is “sufficiently positive” before switching to Coin A, so as to reduce their risk of ending up negative. The problem with this is that the kinds of trajectories that are “sufficiently positive” are rare. It would be better to directly bias movement toward the positive side.

Biasing the trajectory

We can use the difference in step size to do just this. If we use Coin A when our score is positive, then games with score $+1$ will either move to the neutral score of $0$ or move deeper into positive territory to $+2.$ If we use Coin B when our score is negative, then games with score $-1$ will either move deeper into negative territory to $-3$ or be injected directly to positive territory at $+1,$ skipping over the neutral position.

This means that while scores of $+1$ have $0\%$ chance to become negative on the next turn, scores of $-1$ have a $50\%$ chance to become positive on the next turn.

Analytic solution

Now, once a score reaches positive territory (position $+1$ or above) it sees the same transition probabilities that it does when it’s in negative territory (position $-1$ or below).

We can write down the transition equations for how the scores shift along the line to get an analytic result. The only interesting equations are the ones for $-1$ and $0$ as they have unique wiring. This gives

\[f_\text{win} = \frac{811698796376000066208208781649}{1267650600228229401496703205376} \approx 0.6403174472759773\]However, $100$ steps is rather arbitrary and doesn’t yield much insight compared to long times. We just need to find a way to cut through the coupled equations.

Approximate solution

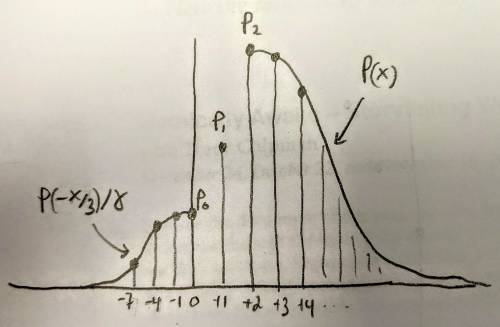

Because the transition rates are symmetric for the positive and negative territories, the shape of the distribution on either side will be identical (accounting for the fact that the step size is $2$ in the negative territory). In other words, \(P(x) = \gamma \cdot P(-x/2),\) where $\gamma$ is some scale-factor greater than $1.$

Adding all negative outcomes and all positive outcomes, the cumulative probability of a negative score $S_{-}$ and the cumulative probability of a positive score $S_+$ are related by

\[S_{+} = \gamma S_{-}.\]Including the probability of getting a $0,$ the winning percentage is

\[\begin{align} f_\text{win} &= \frac{S_+}{S_- + S_+ + P_0} \\\ &= \frac{S_+}{S_+/\gamma + S_+ + P_0}, \end{align}\]but as the system evolves, almost all probability ends up in $S_-$ and $S_+$ so we can ignore the effect of $P_0$, and \(f_\text{win} \approx \dfrac{\gamma}{\gamma+1}.\)

To find $\gamma$, we can look at the update equations from one moment to the next for the positions near the boundary:

\[\begin{align} P_{-1}(t+1) &= \frac{1}{2}P_{-3}(t)+\frac{1}{2}P_0(t) \\\ P_{0}(t+1) &= \frac{1}{2}P_{1}(t) \\\ P_{1}(t+1) &= \frac{1}{2}P_{-1}(t)+\frac{1}{2}P_{0}(t)+\frac{1}{2}P_{2}(t). \end{align}\]On first look this seems like a mess, but we can make some simple approximations:

- at long times the distribution won’t change much in one time step, so $P(t+1) \approx P(t),$ so we can drop the time dependence.

- at long times the distribution is broad, so we can assume $P_{-3} \approx P_{-1}$ and $P_1 \approx P_2.$

With these replacements, the update equations become self-consistent:

\[\begin{align} P_{-1} &\approx \frac{1}{2}P_{-1} + \frac{1}{2}P_0 \\\ P_0 &\approx \frac{1}{2}P_1 \\\ P_1 &\approx \frac{1}{2}P_{-1} + \frac{1}{2}P_0 + \frac{1}{2}P_1 \end{align}\]which we can solve to find $P_{-1} = P_0$ and $P_{1} = 2P_{-1}$ so that $\gamma = 2$ and $f_\text{win} = 2/(2+1) = 2/3.$ Simulating to longer times, the system does indeed converge to $f_\text{win} \approx 0.6\bar{6}.$

Generalizing Coin B

In general, Coin B can have any magnitude (e.g. $\pm 3, 4, 5, \ldots$). In that case, the $-1$ score would have $50\%$ chance to become $-(N + 1)$ or $\left(N - 1\right)$ and similar calculations yield $\gamma = N$ so that $f_\text{win} = N/(N+1).$

In these cases, the peak of the positive territory occurs at $p_N$ and the region from $P_0$ and $P_{N-1}$ forms a staircase of negligible total probability as the system spreads out.

The relevant equations for $N=3$ are

\[\begin{align} P_{-1} &= \frac{1}{2}P_{-1} + \frac{1}{2}P_0 \\\ P_0 &= \frac{1}{2}P_1 \\\ P_1 &= \frac{1}{2}P_0 + \frac{1}{2}P_2 \\\ P_2 &= \frac{1}{2}P_{-1}+\frac{1}{2}P_1+\frac{1}{2}P_2 \end{align}\]which produces $P_0 = \frac{1}{2}P_1,$ $P_1 = \frac{2}{3}P_2,$ and $P_1 = \frac{2}{3}P_2$ so that $P_2 = 3P_0$ and

\[f_\text{win} \approx \frac{\gamma}{\gamma + 1} = \dfrac{3}{4}.\]

In general, all the probabilities between $P_0$ and $P_N$ will be the average of their neighboring probabilities, ensuring the appearance of the $N$-step staircase between the symmetric positive/negative distributions.

Extra credit

When Coin A is biased, so that it lands $+1$ with probability $r$ and $-1$ with probability $(1-r),$ the optimal strategy changes.

If $r < 0.5,$ then it will drift to the left and it makes no sense to use since Coin B by itself offers us a winning percentage of slightly less than $50\%.$ ($50\%$ minus the probability of getting zero: $\binom{100}{50}\frac{1}{2^{100}}.$)

If $r > 0.5$ then it will drift to the right more than $50\%$ of the time, obviating the use of Coin B.

In the second case, the winning percentage is simply

\[f_\text{win} = \sum\limits_{k=N/2+1}^N\binom{100}{k} r^k (1-r)^{N-k}.\]