Question: A game of bingo typically consists of a $5$-by-$5$ grid with $25$ total squares. Each square (except for the center square) contains a number. When a square’s number is called, you place a marker on that square. The goal is to get “bingo,” which is five squares in a row, either across, down, or along one of the two long diagonals. The center square, which doesn’t have a number, is labeled “Free,” and begins with a marker on it before any numbers are called. Here’s an example of a winning $5$-by-$5$ grid in which $10$ squares (other than the “Free” square) have been marked:

Consider a smaller version of the game with a $3$-by-$3$ grid: a “Free” square surrounded by eight other squares with numbers. Suppose each of these eight squares is equally likely to be called, and without replacement (i.e., once a number is called, it doesn’t get called again).

On average, how many markers must you place until you get “bingo” in this $3$-by-$$3$ grid? (The “Free” square doesn’t count as one of the markers—it’s “free”.)

Extra Credit: Instead of a $3$-by-$3$ grid, let’s return to the original $5$-by-$5$ grid.

On average, how many markers must you place until you get “bingo”? (As before, the “Free” square doesn’t count as one of the markers—it’s “free”.)

Solution

I found two ways to dispense with this problem, one approximate and one exact. Because the approximate approach builds intuition for the exact approach, we’ll do that first.

Approximate approach

A board with BINGO has at least one row, column, or diagonal with all its tiles filled in. It may also have some number of other filled tiles that aren’t participating in the BINGO.

Let’s call the side length of the board (in tiles) $n,$ the tiles in a BINGO $\ell,$ the number of BINGO lines on the board $B,$ and the number of spots on the board $S = n^2 - 1.$

The number of ways to place a particular BINGO line on a board with $t$ placed tiles is equal to the number of ways to place the $\ell$ tiles of the BINGO line ($1$ way, by definition) times the number of ways to place the $(t-\ell)$ other tiles. This is just the binomial coefficient

\[\binom{S-\ell}{t-\ell}.\]The total number of ways to pick spots for $t$ tiles is $\binom{S}{t}$ so the probability that a given BINGO line is formed among $t$ placed tiles is

\[\begin{align} P(t) &= \frac{\binom{S-\ell}{t-\ell}}{\binom{S}{t}} \\ &= \frac{(S-\ell)!}{(t-\ell)!}\frac{t!}{S!} \\ &\approx \frac{\left(S-\ell\right)^{S-t}}{S^{S-t}} \\ &= \left(1-\ell/S\right)^{S-t} \\ &\approx e^{-\ell (S-t)/S} \end{align}\]Since there are $B$ possible BINGOs, the expected number of BINGOs in the grid is $ B e^{-\ell(S-t)/S}.$ We can set this equal to $1$ to solve for the number of placed tiles $t_\text{BINGO}$ at which we expect BINGO to first occur

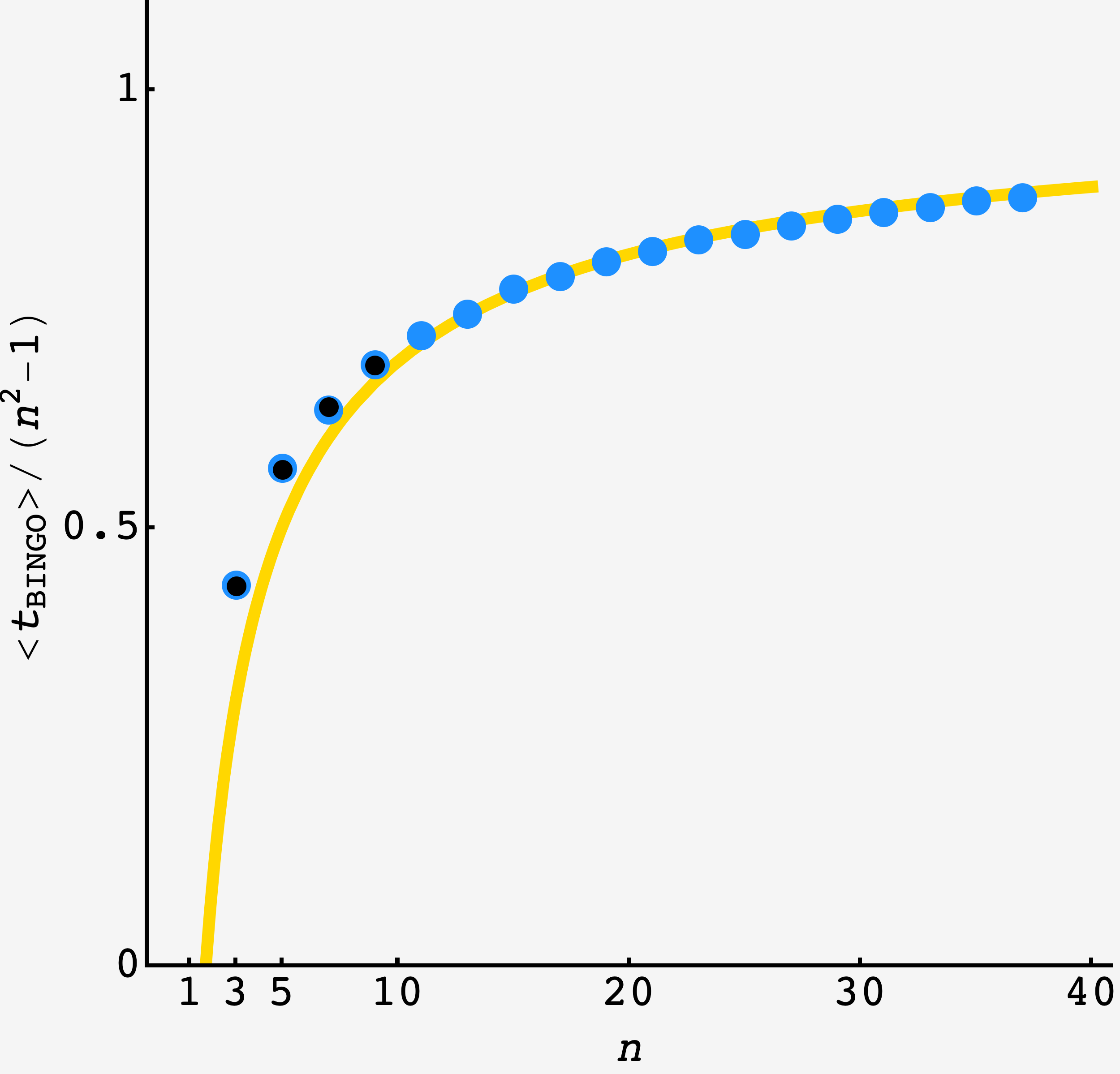

\[\begin{align} t_\text{BINGO} &= S(1-\log B/\ell) \\ &= (n^2-1)\left(1-\frac{\log 2n+2}{n}\right). \end{align}\]Dividing by $S,$ this predicts that, in the limit of the infinite grid, we need to fill in $100\%$ of the tiles before we can expect to make BINGO.

Plotting the prediction (gold curve) for $t_\text{BINGO}/S$ against an $N=1,000$-round simulation (blue dots), there is very good agreement for $n\approx 9$ and above.

The code to run the simulation is below and the logic is to simply fill in one tile at a time and check for horizontal, vertical, or diagonal BINGOs after each fill, stopping at first BINGO.

def new_board(n):

board_list = [ [ 0 for _ in range(n) ] for _ in range(n) ]

board_list[n // 2][n // 2] = 1

return np.array(board_list)

def check_diag(board):

h, w = board.shape

assert h == w

if sum(board[i, i] for i in range(0, h)) == h or\

sum(board[h-1-i, i] for i in range(0, h)) == h:

return True

return False

def check_rows_and_cols(board):

h, w = board.shape

assert h == w

if h in board.sum(axis=1) or h in board.sum(axis=0):

return True

return False

def trial(n):

tiles_placed = 0

board = new_board(n)

board = np.array(board)

while not check_diag(board) and not check_rows_and_cols(board):

open_spots = np.argwhere(board==0)

idx = np.random.randint(0, len(open_spots))

spot = open_spots[idx]

board[spot[0], spot[1]] = 1

tiles_placed += 1

return tiles_placed

def measure(n):

return sum(trial(n) for _ in range(1_000)) / 1_000

Exact approach

To find the exact probability of BINGO with $t$ placed tiles, we can recycle the same idea using the principle of inclusion and exclusion.

We are going to count the number of ways to get at least one BINGO using $t$ tiles, then subtract it from the total number of ways to place $t$ tiles, to get the number of ways to not have BINGO with $t$ placed tiles. We then divide this by the total number of ways to place $t$ tiles to get the probability that BINGO is reached for the first time on the $t^\text{th}$ tiles.

The probability to make BINGO for the first time with the $t^\text{th}$ tile is the probability to not have BINGO after $(t-1)$ tiles, $P_{t-1},$ minus the probability to not have BINGO after $t$ tiles, $P_t.$

Examples for $t=4$ and $5$

Suppose we had $4$ placed tiles in the $3$-by-$3$ grid. we could make BINGO if we have

- one BINGO across an edge, plus another tile placed elsewhere, or

- one BINGO using the free tile at grid center, plus two tiles placed elsewhere.

But these scenarios include and double count the following scenarios

- two BINGOs using the free tile at grid center, or

- one BINGO on an edge, plus a BINGO that uses the center tile that has $1$ tile of overlap with the edge BINGO.

This means that we have to subtract their probability off the total to get rid of the double counting. Since there are no other arrangements with $4$ tiles, we don’t have to worry about larger order unions.

But suppose we were using $5$ tiles. Then it would be possible to form three-BINGO grids. For example, a BINGO on the top edge plus both diagonal BINGOs would use a total of $5$ unique tiles.

In cases like this, subtracting the double counted two-BINGO scenarios would completely remove the three-BINGO scenarios, and we’d have to add them back in.

As we go to higher and higher numbers of tiles, we have to consider higher and higher order unions of BINGO lines. This is the principle of inclusion exclusion.

Counting

Now we have to figure out how to count the total number of two-BINGO unions, three-BINGO unions, four-BINGO unions, and so on.

First, let’s form the set of valid BINGOs, $\mathcal{B} = \{B_1, B_2,\ldots, B_{2n+2}\},$ which consists of the four edge BINGOs, the two diagonal BINGOs, and the vertical and horizontal BINGOs through the center tile. Suppose we select the top edge and one of the diagonals and use $6$ tiles total. First we form the union of the tiles for the top edge and the diagonal, giving $4$ tiles. After that, the grid has $4$ open tiles, and we have $2$ tiles left to place. This means there are $\binom{4}{2}$ ways to form this particular double (or more) bingo using $6$ tiles.

The exact number of ways to make one or more BINGOs with $t$ placed tiles is equal to the sum

\[N_k = \sum_{k=1}^{\lvert \mathcal{B}\rvert} \sum \limits_{U_i\in\mathcal{B}^k} (-1)^k\lvert U_i\rvert,\]where $\mathcal{B}^k$ is the set of all order-$k$ unions of BINGO lines.

The probability to have no BINGO after $k$ tiles is

\[P_k = \frac{\dbinom{S}{k} - N_k}{\dbinom{S}{k}}.\]The expected waiting time is then just

\[\begin{align} \langle T \rangle &= 1\cdot(P_1-P_2) + 2\cdot(P_2-P_3) + 3\cdot (P_3-P_4) + \ldots \\ &= P_1 + P_2 + P_3 + \ldots \\ &= \sum_j P_j, \end{align}\]with the sum cutting off once $P_k = 0.$

Running the calculation for $n=\{3,5,7,9\}$ we get

\[\begin{array}{c|c|l} n & \approx \langle T_n\rangle & \text{exact} \\ \hline 3 & 3.4714 & \tfrac{243}{70} \\ 5 & 13.6081 & \tfrac{4245967}{312018} \\ 7 & 30.6284 & \tfrac{92808815885976862254547855048255717828975268813516294590711697630741949917}{3030156855561123136083569432402469935904800154652176659373770587819474200} \\ 9 & 54.8798 & \tfrac{9480193784403964822668977370061651864424070012917934616146950600296441356471113983815890530994346526443281111044132125843376970934829947366459607396565066156948466186172118583527867781080122906218539058347085335964151443756760607393153051628950923647295138918187039937968503700462654709127053270665396153075596607017964933926957231603401222798969173888596249562283448902274588358546352472126268488114903344092231}{172744644337983342139871248184854688995399875294022764144063097631520019197293651487735553968605143077150035193594383989551717259799448101768380079366227260933208924561364376237585648727148845963146818037065707773804024594544145390059490180652843086658750570455296956041095473343892404240566891396626835929539826453735232895578099989553698179671195844317163873729200176533873840933045973251072570411414570415760} \end{array}\]These points are plotted in black on the graph above, and overlap perfectly with the simulation.

from itertools import combinations

import scipy as sp

import fractions as F

def count(n, t):

BINGO_VERTICAL = [ set((i, j) for i in range(n)

if (i, j) != (n // 2, n // 2))

for j in range(n) ]

BINGO_HORIZONTAL = [ set((i, j) for j in range(n)

if (i, j) != (n // 2, n // 2))

for i in range(n) ]

BINGO_DIAGONAL = [ set((i, i) for i in range(n)

if (i, i) != (n // 2, n // 2)) ]

BINGO_ANTI_DIAGONAL = [ set((i, n - 1 - i) for i in range(n)

if (i, n - 1 - i) != (n // 2, n // 2)) ]

BINGOS = BINGO_VERTICAL + BINGO_HORIZONTAL \

+ BINGO_DIAGONAL + BINGO_ANTI_DIAGONAL

total = 0

tiles_on_board = n ** 2 - 1

for group_size in range(1, len(BINGOS)):

combos = combinations(BINGOS, group_size)

for com in combos:

tiles_in_bingo = len(set.union(*com))

tiles_left = tiles_on_board - tiles_in_bingo

ways = sp.special.comb(tiles_left, t - tiles_in_bingo)

if len(com) % 2 == 0:

total -= ways

else:

total += ways

S = sp.special.comb(tiles_on_board, t)

return F.Fraction(

int(S - total),

int(S)

)

def exact(n):

k = 0

total = 0

while True:

new = count(n, k)

if new > 0:

total += new

else:

break

k+= 1

return total

Beyond $n=9,$ the run time for this naive implementation is too long to finish.