Question: I was recently a guest at Disney World, which has a new system called “Lightning Lane” for reserving rides in advance—for a fee, of course.

By purchasing “Lightning Lane Multi Pass,” you can reserve three of the many rides in a park, with each ride occurring at a different hourlong time slot. For simplicity, suppose the park you’re visiting (let’s say it’s Magic Kingdom) has 12 such time slots, from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m. So if you have the 3 p.m. time slot for a ride, then you can skip the “standby lane” and board the much shorter “Lightning Lane” at any point between 3 and 4 p.m. Assume you can complete at most one ride within each hourlong time slot.

Once you have completed the first ride on your Multi Pass, you can reserve a fourth ride at any time slot after your third ride. This way, you always have at most three reservations. Similarly, after you have completed your second ride, you can reserve a fifth ride at any time slot after your fourth, and so on, up until you are assigned a ride at the 8 p.m. (to 9 p.m.) time slot. That will be your final ride of the day.

Magic Kingdom happens to be very busy at the moment, and so each ride is randomly assigned a valid time slot when you request it. The first three rides of the day are equally likely to be in any of the 12 time slots, whereas subsequent rides are equally likely to occur in any slot after your currently latest scheduled ride.

On average, how many rides can you expect to “Lightning Lane” your way through today at Magic Kingdom?

Extra Credit

If you’re a Disney aficionado, then you know that week’s Fiddler is in fact an oversimplification of how Lightning Lane actually works. Let’s make things a little more realistic.

This time around, after you complete the first ride on your Multi Pass, you can reserve a fourth ride at any time slot after your first completed ride (rather than after your third ride). Similarly, after you have completed your second ride, you can reserve a fifth ride at any time slot after your second completed ride, and so on, until there are no available time slots remaining.

As before, the first three rides of the day are equally likely to be in any of the 12 time slots, whereas subsequent rides are equally likely to occur in any remaining available slots for the day.

On average, how many rides can you expect to “Lightning Lane” your way through today at Magic Kingdom?

Solution

With the approach taken here, the extra credit is simpler so we’ll solve it first.

Extra credit

The day starts off with the random assignment of three time slots out of the $12$ available. After we finish the first ride, we are randomly assigned another time slot out of those that have yet to occur. This is equally likely to add any of the remaining time slots to the schedule, even if it starts before one of the currently scheduled rides.

This means that after the first ride, we’re in the same position as we were before: in possession of a three-ride schedule with some number of free time slots available for further assignment.

Let’s think about the set of all possible initial schedules given $N$ total time slots, $\mathcal{S}_N$, and pick one schedule from it at random:

- if the schedule we pick doesn’t use the first time slot (probability $(1-3/N)$), then we’re in a situation we could start out in with $(N-1)$ time slots, i.e. the schedule is in $\mathcal{S}_{N-1}$, and

- if the schedule we picked does use the first timeslot (probability $3/N$) then once we take the first ride, we will have a schedule that’s in $\mathcal{S}_{N-1}.$

For example, take $N=6$ and an initial schedule $(2,4,6).$ This is a situation we could have been in with $N=5$ time slots. Since we have effectively wasted the first time slot by not picking it, we can map the labels $2\rightarrow 1, 4\rightarrow 3,$ and $6\rightarrow 5$ to get $(1,3,5),$ a bona fide schedule in $\mathcal{S}_{N-1}.$

By contrast, if our initial schedule is $(1,4,6)$, then after we take the first ride we’ll draw another time slot (either $2$, $3$, or $5$), giving schedules $(2,4,6)$, $(3,4,6)$ or $(4,5,6)$ plus one completed ride.

This lets us relate expectations. If we call $R_N$ the number of rides we expect with $N$ timeslots, the above argument becomes

\[\begin{align} R_N &= \frac3N \left(1 + R_{N-1}\right) + \left(1-\frac3N\right)R_{N-1} \\ &= R_{N-1} + \frac3N. \end{align}\]So, adding an $N^\text{th}$ timeslot to the system adds $3/N$ extra rides in expectation. Following the recursion down, we get

\[\begin{align} R_N &= \frac3N + R_{N-1} \\ &= \frac3N + \frac3{N-1} + R_{N-2} \\ &= 3\left(\frac1N + \frac1{N-1} + \ldots + \frac15 + \frac14\right) + R_3 \\ &= 3\left(H_{N} - \frac13 - \frac12 - 1\right) + 3 \\ &= 3H_{N} - \frac52 \\ \end{align}\]where $H_N$ is the $N^\text{th}$ harmonic number. For $N=12,$ this is equal to

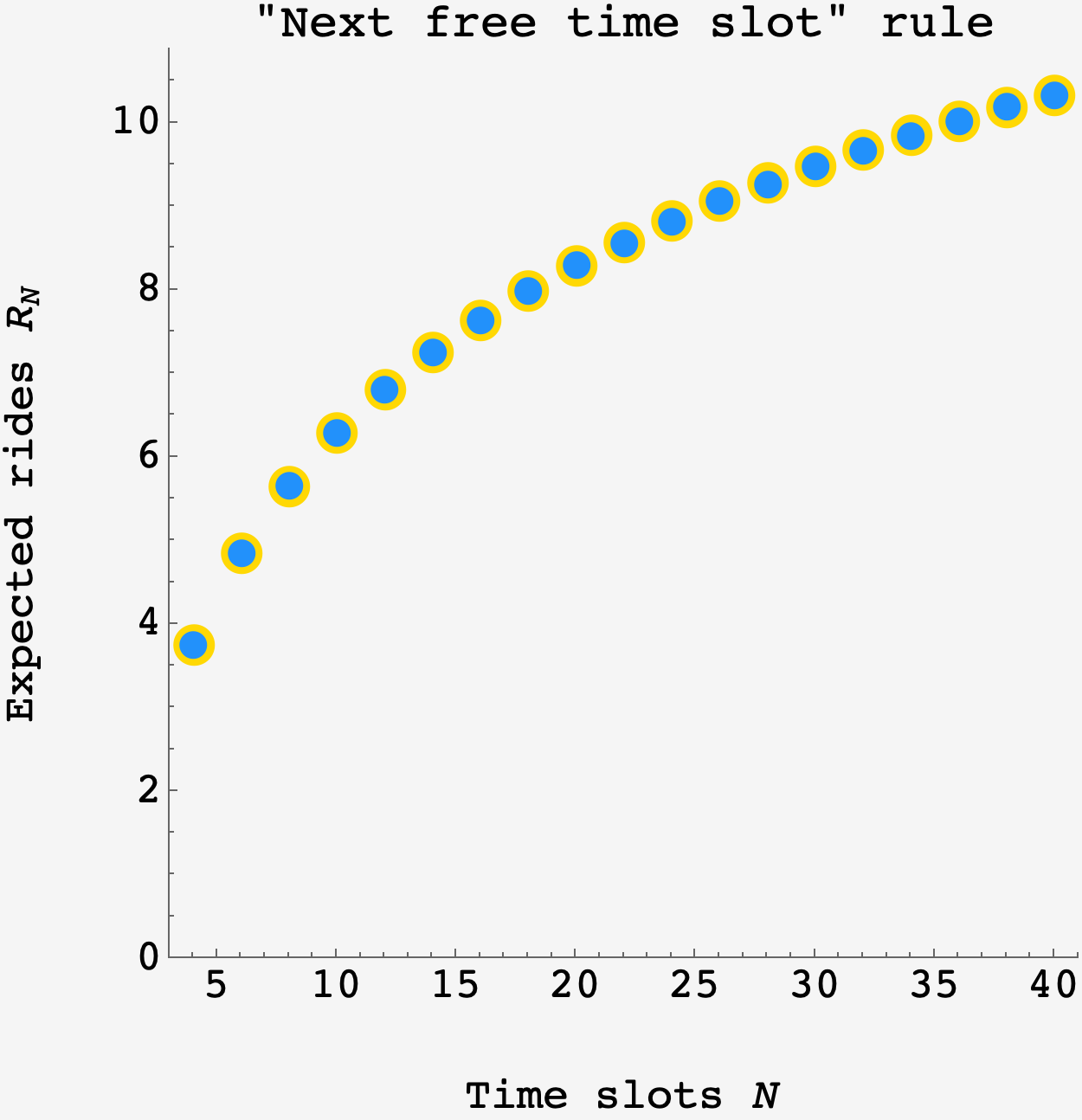

\[\begin{align} R_{12} &= 3H_{12} - 5/2 \\ &= \frac{62921}{9240} \\ &\approx 6.80963\,\text{rides} \end{align}\]Plotting the calculation (gold points) alongside a $10^6$ trial simulation (blue points), there is good agreement:

The standard problem is actually more complicated than this. Whereas in the extra credit the first time slot in our schedule determines the number of remaining time slots, the standard credit conditions this on the maximum time slot in our schedule.

Standard credit

After we take our first ride, we’re playing a new game where we have $r$ remaining time slots, and we continue drawing from the remainder until we reach the final time slot.

Let’s call this second phase the endgame, and the expected number of rides we get from it $E_r$. The number of time slots $r$ in the endgame is determined by the latest time slot we got in our original allotment of $3$ random time slots.

The probability that our latest scheduled time slot in the original draw is $r$ is $P(r) = \binom{r-1}{2}/\binom{12}{3},$ that’s because we know the third time slot is at $r$ (probability $1$) and there are $\binom{r-1}{2}$ ways to pick $2$ slots less than $r.$

So, the expected number of rides is

\[R_N = \sum_{r=3}^{N}\left(3 + E_{N-r}\right)P(r).\]As with the extra credit, we can find the value of the endgame by comparing the endgame with $r$ remaining time slots to the one with $(r-1)$ remaining time slots:

\[\begin{align} E_r &= 1/r \left(1 + E_{r-1}\right) + \left(1-1/r\right)E_{r-1} \\ &= \frac1r + E_{r-1} \end{align}\]and $E_r = 1/r + 1/(r-1) + \ldots + 1/2 + 1 = H_r. $

So the expected number of rides is,

\[R_N = \sum_{r=3}^N \left(3 + H_{N - r}\right)\dfrac{\binom{r - 1}{2}}{\binom{N}{3}},\]which actually simplifies to $H_N + 7/6.$ For $N=12$ this equals $118361/27720 \approx 4.26988$ rides.

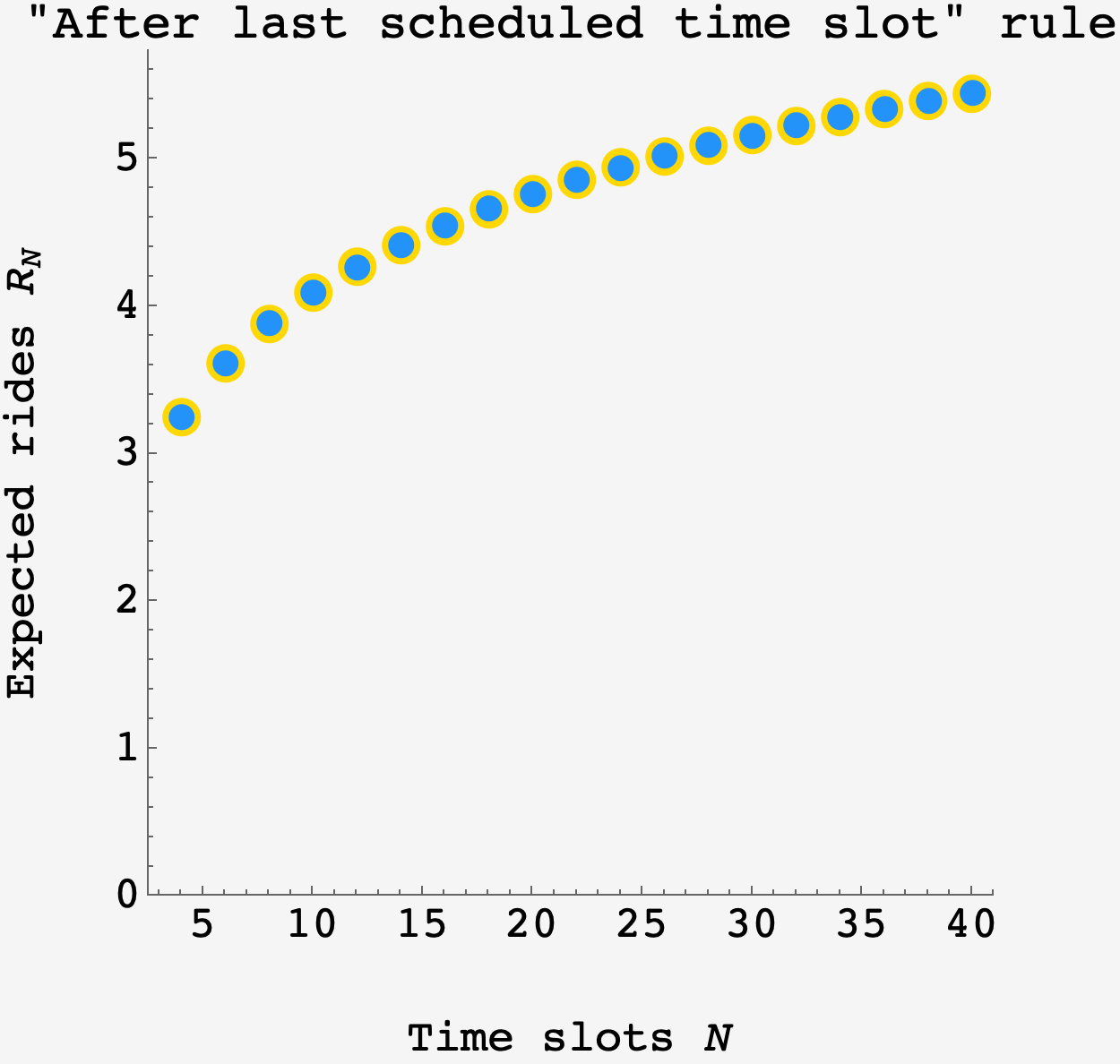

Plotting the series (gold points) alongside a $10^6$ trial simulation (blue points), there is good agreement once again.

The gains from additional time slots take a while to accumulate. While we’re guaranteed $3$ in the $N=3$ time slot scenario, by $N=70$ time slots the expected number of rides is just under $6,$ meaning about half the value is still from the initial allotment.

Comparing the two schemes for large $N,$ the “next free time slot” rule allots about three times as many time slots as the “after last scheduled time slot” rule.