Question: You’ve been asked to draw a 3D sketch of the function ${z = \vert x\rvert + \lvert y\rvert}.$ As you’re about to do this, you are struck by another bout of dizziness, and your resulting graph is randomly rotated in $3\text{D}$ space.

More specifically, your graph has the correct origin. But the true $z$-axis is equally likely to point from the origin to any point on the surface of the unit sphere. (Meanwhile, the $x$-axis is equally likely to point in any direction perpendicular to the $z$-axis. From there, the $y$-axis is uniquely determined.)

What is the probability that the resulting graph you produce is in fact a function (i.e., $z$ is a function of $x$ and $y$)?

Solution

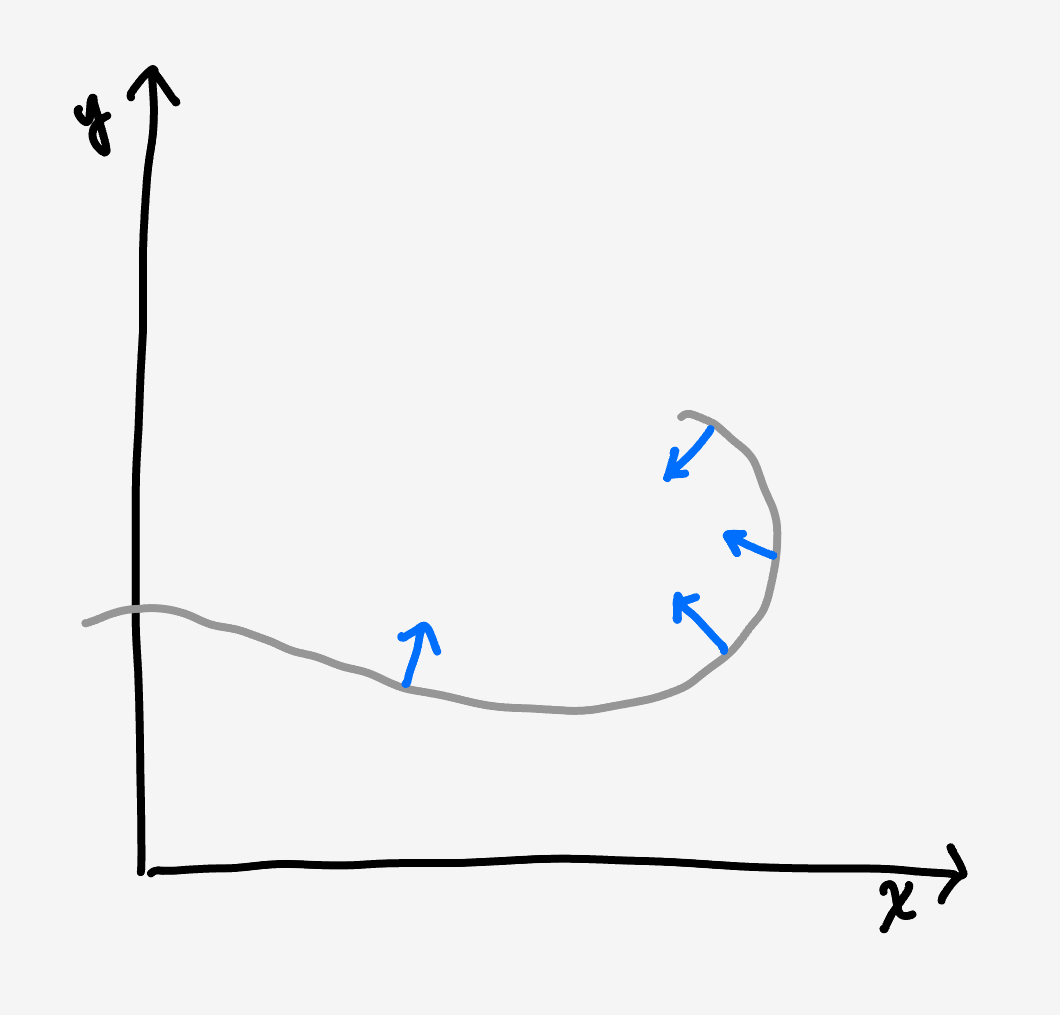

If a function is a function, then it can’t flip over. This means that the direction the surface faces needs to always point up or always point down. For example, this curve, which is not a function, sees the blue arrow switch from pointing overall up to overall down:

More concretely, the $z$ component of the surface normal switches from positive to negative. This gives us an unambiguous condition to test if our tumbled surface is a function.

Luckily, our surface ${z = \lvert x\rvert + \lvert y\rvert}$ is the union of $4$ planes, so we can just inspect $4$ normal vectors.

Changing our perspective

Instead of tumbling the surface to find a random new orientation, we can equivalently pick a random new direction for the vertical. This is more convenient since it means we can keep constant coordinates for the $4$ faces of the surface ${z = \lvert x\rvert + \lvert y\rvert.}$

The $4$ faces have the surface normals

\[\begin{align} \mathbf{n}_1 &= (+1, +1, +1) \\ \mathbf{n}_2 &= (-1, +1, +1) \\ \mathbf{n}_3 &= (+1, -1, +1) \\ \mathbf{n}_4 &= (-1, -1, +1). \end{align}\]If we pick a random direction ${\mathbf{v} = (v_x, v_y, v_z)}$ for the new vertical, then the vertical component of a vector $\mathbf{n}$ in the new coordinates is just ${\mathbf{n}\cdot\mathbf{v}.}$ Taking the dot product of $\mathbf{v}$ with the normal of each face, we get four equations:

\[\begin{align} v_z &> v_x + v_y \\ v_z &> -v_x + v_y \\ v_z &> v_x - v_y \\ v_z &> -v_x - v_y. \\ \end{align}\]Since all these equations have to hold at once, they reduce to

\[v_z > \lvert v_x\rvert + \lvert v_y\rvert.\]Finding the subset

What we want to know is, if we draw $\mathbf{v}$ at random from the surface of the unit sphere, what is the chance this condition holds? To answer that we have to find the subset of $(\theta,\phi)$ that satisfy it.

Writing $\mathbf{v}$ in spherical coordinates, we can see

\[\mathbf{v} = (\cos\theta\cos\phi, \cos\theta\sin\phi, \sin\theta).\]In this representation, the inequality is

\[\frac{\sin\theta}{\lvert \cos\theta\rvert} > \lvert\cos\phi\rvert + \lvert\sin\phi\rvert.\]This identifies the set of $(\theta,\phi)$, and it consists of two four-cornered patches:

Exploiting the symmetry, we can use just one octant of the sphere and drop the absolute value signs. Taking $\theta$ and $\phi$ to be between $0$ and $\frac12\pi$ the condition simplifies to

\[\theta > \tan^{-1}\left(\cos\phi + \sin\phi\right).\]To find the area of the patches relative to the sphere, we can add the points in this set. Integrating the differential surface area patch $\text{d}\Omega = \cos\theta\,\text{d}\theta\,\text{d}\phi$, we get:

\[\begin{align} P(\text{tumble is a function}) &= \dfrac{\displaystyle \int\limits_0^{\frac12\pi}\text{d}\phi\,\hspace{-2em} \int\limits_{\tan^{-1}\left(\cos\phi + \sin\phi\right)}^{\frac12\pi} \hspace{-2em} \cos\theta\,\text{d}\theta}{\displaystyle\int\limits_0^{\frac12\pi}\text{d}\phi\, \int\limits_0^{\frac12\pi} \cos\theta\,\text{d}\theta} \\ &= \dfrac2\pi\left(\frac\pi2 - 2\sin^{-1}\frac1{\sqrt{3}}\right) \\ &\approx 0.2163 \end{align}\]