Question: Suppose you have two real numbers, like $3.14$ and $2.718.$ If you round these two numbers and add these rounded values together, you get $3 + 3,$ or $6.$ Alternatively, if you add the original two numbers and then round the sum, you still get $6.$

But rounding then adding doesn’t always give you the same result as adding then rounding. For example, if the two numbers are $2.4$ and $3.4,$ rounding then adding gives you $5$ (i.e., $2 + 3$), whereas adding then rounding gives you $6$ (i.e., $2.4 + 3.4 = 5.8,$ which rounds to $6$).

How likely is it that rounding then adding gives you the same result as adding then rounding?

To be more precise, suppose you randomly, uniformly, and independently pick two real numbers between $0$ and $1.$ What is the probability that rounding the two numbers and then adding gives you the same result as adding the two numbers and then rounding?

Instead of picking two numbers from the interval between $0$ and $1,$ suppose you randomly and independently pick $N$ numbers.

What is the probability that rounding each of the $N$ numbers and then adding gives you the same result as rounding the sum of the $N$ numbers?

Solution

The problem is to see how often the sum of the rounds will equal the round of the sums. Put plainly, this will hold when the sum lands in a unit band around the number of rounded up numbers.

But it helps to think about this problem from a more physical perspective.

Physical intuition

Suppose we take a sum of fifty random uniform variables $x_j$ and $35$ of them turn out to be in $\left(\frac12, 1\right).$

Then we can say $U=35$ numbers have rounded up, and $D = (N-U) = 15$ have rounded down. The round of the sum equals the sum of the rounded numbers if $\sum_j x_j$ falls between $(35-\frac12)$ and $(35+\frac12).$

We can think of each $U$ step as a big step, and each of the $D = (N-U)$ steps as small ones. Then the sum is a walk that randomly switches between big and small steps.

In this picture, the original question is equivalent to this more practical one: if all we know are the kinds of steps taken ($U$ and $D$), how often can we locate the walker to within $1$ of their actual position?

Many steps

As we accumulate more and more steps, the jaggedness of the individual unit variables dies off, the central limit theorem takes hold, and the sum becomes normally distributed.

Big steps have mean $\frac34$ and small steps have mean $\frac14,$ so, if we have $U$ roundups, the expected position of the walker is

\[\begin{align} \mu_U &= \frac14(N-U) + \frac34U \\ &= \frac14N + \frac12U. \end{align}\]Also, the walker’s position has an expected variance of

\[\begin{align} \sigma^2_U &= N\sigma^2_\text{step} \\ &= N \langle x - \langle x\rangle\rangle^2 \\ &= 2N\int\limits_0^{\frac12}\text{d}x\, \left(x - \frac14\right)^2 \\ &= \frac{1}{48}N. \end{align}\]This means the walker’s destination becomes a normal variable with mean $\mu_U$ and variance $\sigma^2_U.$

The two kinds of roundings agree if the walker terminates between $(U-\frac12)$ and $(U+\frac12).$ So the probability of agreement for a given $U$ is

\[P(\text{agree}\rvert U) = \int\limits_{U-\frac12}^{U+\frac12}\text{d}x\, \mathcal{N}_x(\mu_U, \sigma^2_U)\]We could evaluate this, but it will bring error functions into our lives. Since $\left(U-\frac12\right)$ and $\left(U+\frac12\right)$ are close, we can approximate this as simply the value of the integrand at $U$ times the interval’s unit width:

\[P(\text{agree}\rvert U) \approx \mathcal{N}_U(\mu_U, \sigma^2_U)\]Weighted average

The total probability of agreement is just the weighted average over all possible numbers of roundups $U$

\[P(\text{agree}) = \int\text{d}U\, P(\text{agree}\rvert U) P(U).\]The probability of $U$ roundups is the binomial distribution

\[P(U) = \frac{1}{2^N}\binom{N}{U}.\]Happily, $P(U)$ is easily approximated with another normal distribution, $\mathcal{N}_U\left(\frac12 N, \frac14 N\right),$ so the probability of agreement is

\[P(\text{agree}) = \int\limits_0^N\text{d}U\, \mathcal{N}_U\left(\mu_U, \sigma^2_U\right) \mathcal{N}_U\left(\frac12 N, \frac14 N\right),\]which comes out to

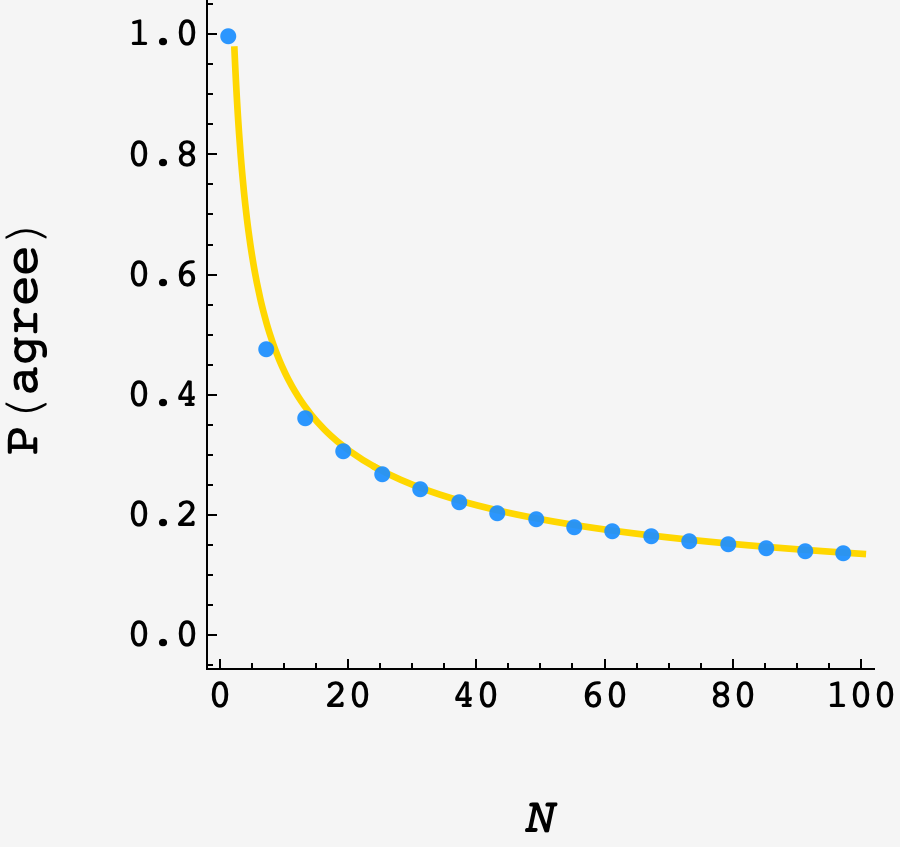

\[P(\text{agree}) \approx \sqrt{\frac{6}{\pi N}}.\]Plotting it against a simulation, we see good agreement as $N$ grows:

While the integral is fun to work out by hand, this sympy will also do the trick:

from sympy import *

init_printing(use_unicode=False)

x, k, u, n = symbols(('x', 'k', 'u', 'n'), positive=True)

mean_walk, var_walk = Rational('1/4') * n + Rational('1/2') * u, Rational('1/48') * n

mean_U, var_U = Rational('1/2') * n, Rational('1/4') * n

fun = 1/sqrt(2 * pi * var_walk) * 1/sqrt(2 * pi * var_U) * \

integrate(

exp(-(u-mean_walk) ** 2 / (2 * var_walk)) * \

exp(-(u-mean_U) ** 2 / (2 * var_U))

,(u, -oo, +oo)

)

simplify(fun.subs({n:n}))