Question: A long time ago, there once was a riddle about cars getting caught in traffic jams. You could say that one really stuck with me.

In the original puzzle, there were $N$ cars on a long, straight highway with a single lane. Each car traveled in the same direction but at a constant speed that was unique and randomly selected. However, if a driver caught up to another, slower car (or a group of cars similarly blocked by that slower car), they remained stuck behind that slower car.

This time around (as suggested by one of the original puzzle’s extension problems), a second lane opens up. The catch is that there is only one entry point into this second lane, so each car has exactly one opportunity to decide whether to proceed into this second lane.

From the first car in the original lane to the last car, each decides whether to make the switch to the second lane as it passes. Fortunately, each car knows the speed of every other car, so each will make the switch provided that it can ultimately proceed at a greater speed (whether on its own or as part of a faster group).

On average, how many total groups of cars will eventually form in the two lanes?

Solution

Each additional driver introduces an expected number of additional groups $\langle G_i\rangle$, making the total

\[\langle \text{num groups}\rangle_N = \langle G_1\rangle + \langle G_2\rangle + ... \langle G_N\rangle.\]Now, the $i^\text{th}$ driver has a $1/i$ chance of being the $1^\text{st}$ fastest, or $2^\text{nd}$ fastest, all the way up to being the $i^\text{th}$ fastest driver out of the first $i$ drivers to reach the entry point.

If they are the first fastest, then they will only introduce a new group if all $(i-1)$ drivers before them are in increasing order. If they are $(i-1)$ fastest, they will only introduce a new group of the top $(i-2)$ drivers are in increasing order, and so on.

If those drivers weren’t in increasing order, then at least one driver who is slower than them would have found it advantageous to switch lanes, meaning that both lanes already have a group moving slower than them, blocking them from making a new group at their own speed

So,

\[\langle G_i\rangle = \frac{1}{i}\left[1 + 1 + 1/2! + ... 1/(i-1)!\right]\]and

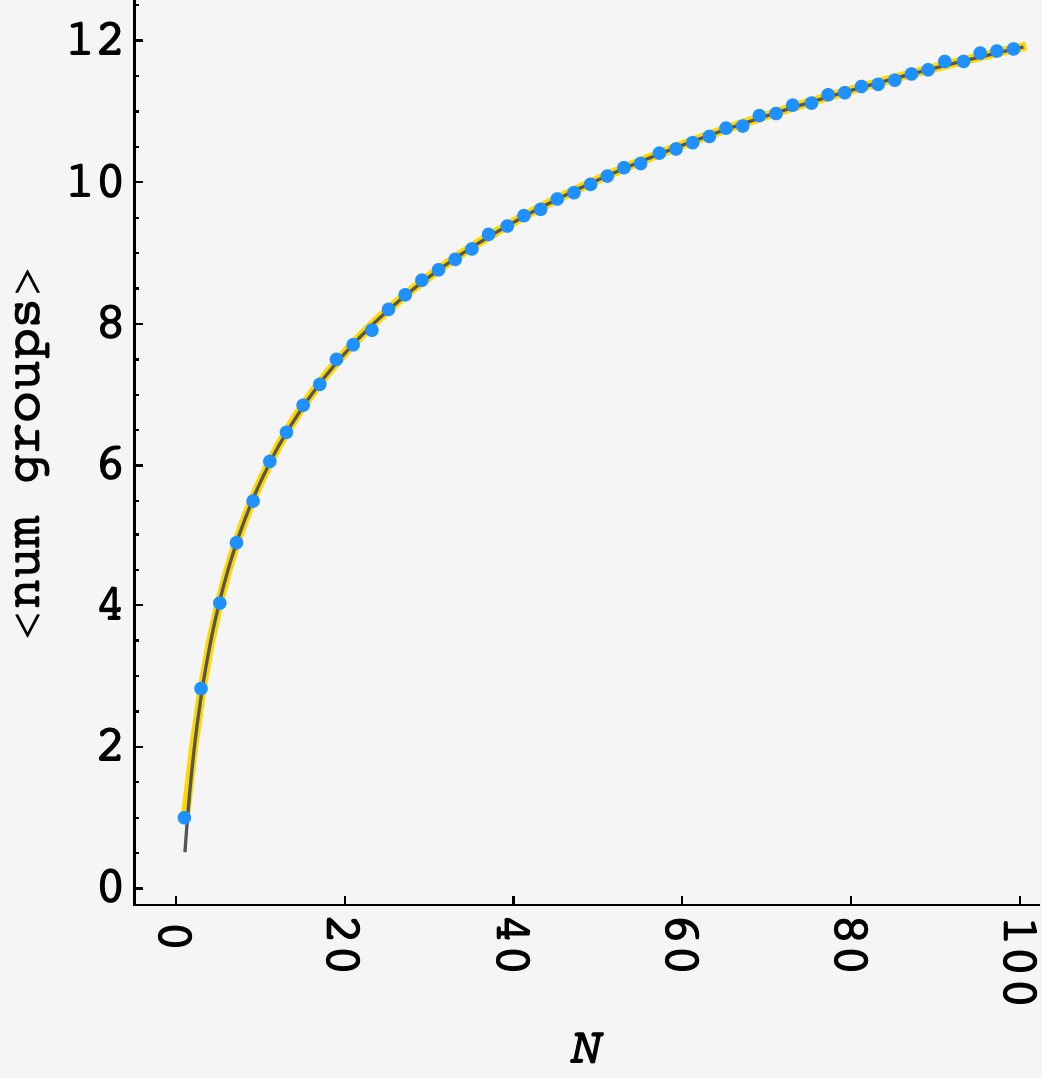

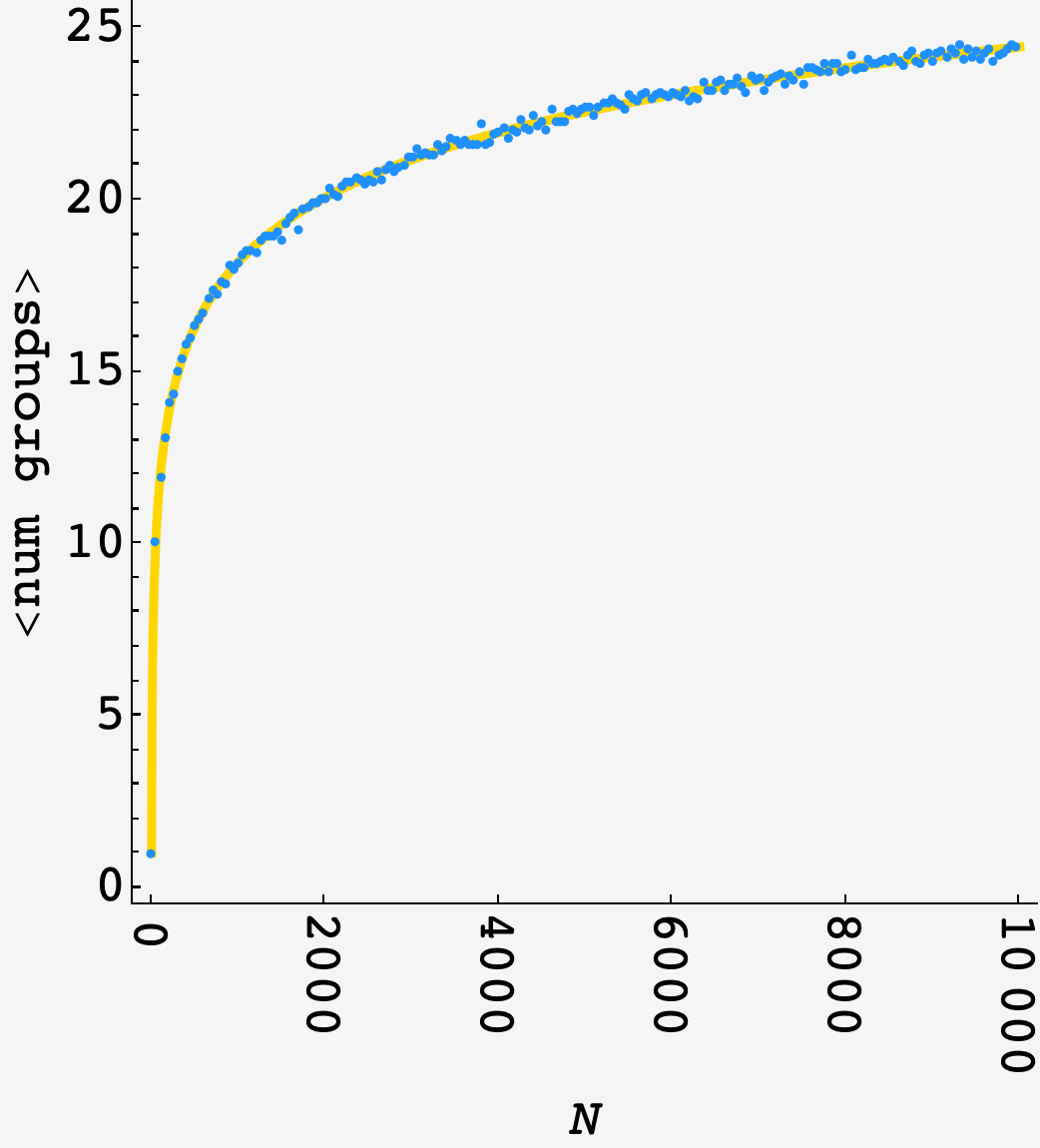

\[\langle\text{num groups}\rangle_N = \sum_{i=1}^N\frac1i\sum\limits_{j=0}^{i-1} \frac{1}{j!}.\]Plotting this (gold) next to a $10^3$ round simulation (blue) shows good agreement:

In the high-$N$ limit, this becomes

\[\langle\text{num groups}\rangle_N = H(N)e + O(1).\]Plotting the approximation (dark gray) alongside the previous results shows good agreement at low $N$: