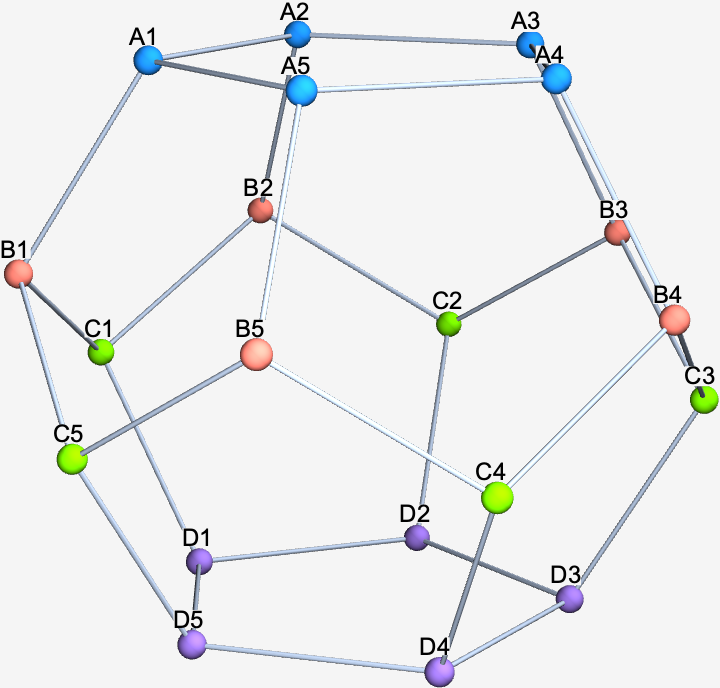

Question: Andy the ant has spent most of his days living on a strange land consisting of white hexagons that are surrounded by alternating black pentagons and white hexagons (three of each), and black pentagons surrounded by five white hexagons. To us this land is familiar as the classic soccer ball we see above on the left. Due to Andy’s tiny size and terrible eyesight, he doesn’t notice the curvature of the land and avoids the black pentagons because he suspects they may be bottomless pits.

Every morning he wakes up on a white hexagon, leaves some pheromones to mark it as his special home space, and starts his random morning stroll. Every step on this stroll takes him to one of the three neighboring white hexagons with equal probability. He ends his stroll as soon as he first returns to his home space. As an example, on exactly $1/3$ of mornings Andy’s stroll is $2$ steps long, as he randomly visits one of the three neighbors, and then has a $1/3$ probability of returning immediately to the home hexagon.

This morning, his soccer ball bounced through a kitchen with an infinite (at least practically speaking…) regular hexagonal floor tiling consisting of black and white hexagons, a small part of which is shown above on the right. In this tiling every white hexagon is surrounded by alternating black and white hexagons, and black hexagons are surrounded by six white hexagons. Andy fell off the ball and woke up on a white hexagon. He didn’t notice any change in his surroundings, and goes about his normal morning routine.

Let $p$ be the probability that his morning stroll on this new land is strictly more steps than the expected number of steps his strolls on the soccer ball took. Find $p$, rounded to seven significant digits.

Solution

Andy walks in two kinds of places, the finite surface of the soccer ball and the infinite kitchen floor.

On the ball, he can only walk so far into the forest before he starts to walk out. But on the kitchen floor, his walks are much more likely to range up in length. The further he gets, the more likely he is to get further.

We want to know if he’ll have an exceptional experience in the kitchen. Since this depends on knowing the expected walk on his soccer ball, we’ll start there.

Soccer ball by symmetry

On the soccer ball, suppose we let Andy to wander indefinitely. How often would we expect him to be on a given position? Since all positions on the ball are equivalent, the answer is simply $1$ out of $n$ of the time.

It may seem like this is too cute, since Andy isn’t indefinitely wandering but starting from a definite position. However, any subsequence in the infinite wander from $i$ back to $i$ is a valid morning stroll.

Still, we can calculate explicitly to verify that expected time to return is indeed $20$ steps.

Soccer ball by calculation

Whenever Andy takes a step, he has a $\frac13$ chance to move onto some neighboring tile $j$ in $\sigma(i),$ the neighborhood of $i,$ which has an expected number of additional tiles $\langle T_j\rangle$ before it returns to the origin for the first time. Putting this to symbols gets the harmonic relationship

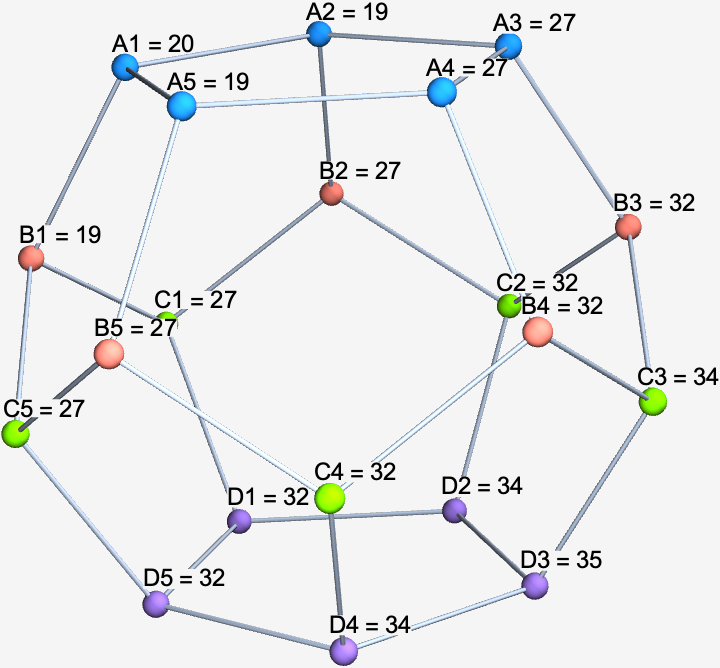

\[\langle T_i\rangle = 1 + \frac13\sum\limits_{j\in\sigma(i)\setminus\boldsymbol{0}} \langle T_j\rangle.\]To get rolling, we just have to encode the neighbor relationships of the white tiles on the ball. Taking its vitals, we see that the $20$ white tiles can be arranged into $4$ groups ($A,$ $B,$ $C,$ and $D$). The top and bottom groups form connected rings while the middle two undulate, connecting to members of the other ring, and the top or bottom, but not amongst themselves.

Putting this to a graph, we can generate the system of expectation equations like

edges = {A1 <-> A2, A2 <-> A3, A3 <-> A4, A4 <-> A5, A5 <-> A1,

A1 <-> B1, A2 <-> B2, A3 <-> B3, A4 <-> B4, A5 <-> B5,

B1 <-> C1, B1 <-> C5, B2 <-> C1, B2 <-> C2, B3 <-> C2,

B3 <-> C3, B4 <-> C3, B4 <-> C4, B5 <-> C4, B5 <-> C5,

C1 <-> D1, C2 <-> D2, C3 <-> D3, C4 <-> D4, C5 <-> D5,

D1 <-> D2, D2 <-> D3, D3 <-> D4, D4 <-> D5, D5 <-> D1};

(* form the expectation relations for each tile*)

equations = (# == 1 + 1/3 Total[AdjacencyList[g, #]]) & /@ VertexList[g];

(* set A1 to zero in all equations but its own *)

system = Join[{eqns[[1]]}, eqns[[2 ;; -1]] /. {A1 -> 0}];

(* solve the system *)

sols = First@Solve[system, VertexList[g]]

> {A1 -> 20, A2 -> 19, A3 -> 27, A4 -> 27, A5 -> 19,

> B1 -> 19, B2 -> 27, B3 -> 32, B4 -> 32, B5 -> 27,

> C1 -> 27, C2 -> 32, C3 -> 34, C4 -> 32, C5 -> 27,

> D1 -> 32, D2 -> 34, D3 -> 35, D4 -> 34, D5 -> 32}

Putting these back on the ball, we see that the expected waiting time increases as we move away from the starting point, up until a maximum at the furthest point, $D_3.$ As expected, the expected waiting time at each of $A_1$’s neighbors is $1$ less than $T(A_1).$

So, we’ll be finding the probability that his kitchen walk goes longer than $\langle T\rangle_\text{soccer} = 20.$

Kitchen constitutional

In the kitchen, the lattice is bigger and it pays to be smart before diving in.

If Andy starts from the marked tile, then his first options are to take a unit step — i.e. $\left(\cos\theta,\sin\theta\right)$ — in one of the directions $\{\frac{\pi}{6}, \frac{5\pi}{6}, -\frac{3\pi}{2}\}.$ On the second step, his options are the same, but reflected about the $x$-axis: $\{-\frac{\pi}{6}, -\frac{5\pi}{6}, \frac{3\pi}{2}\}.$

Since Andy’s walks return to the origin, they’ll have an even number of steps. This means we can focus on tiles that are an even number of steps from the origin and ignore the others.

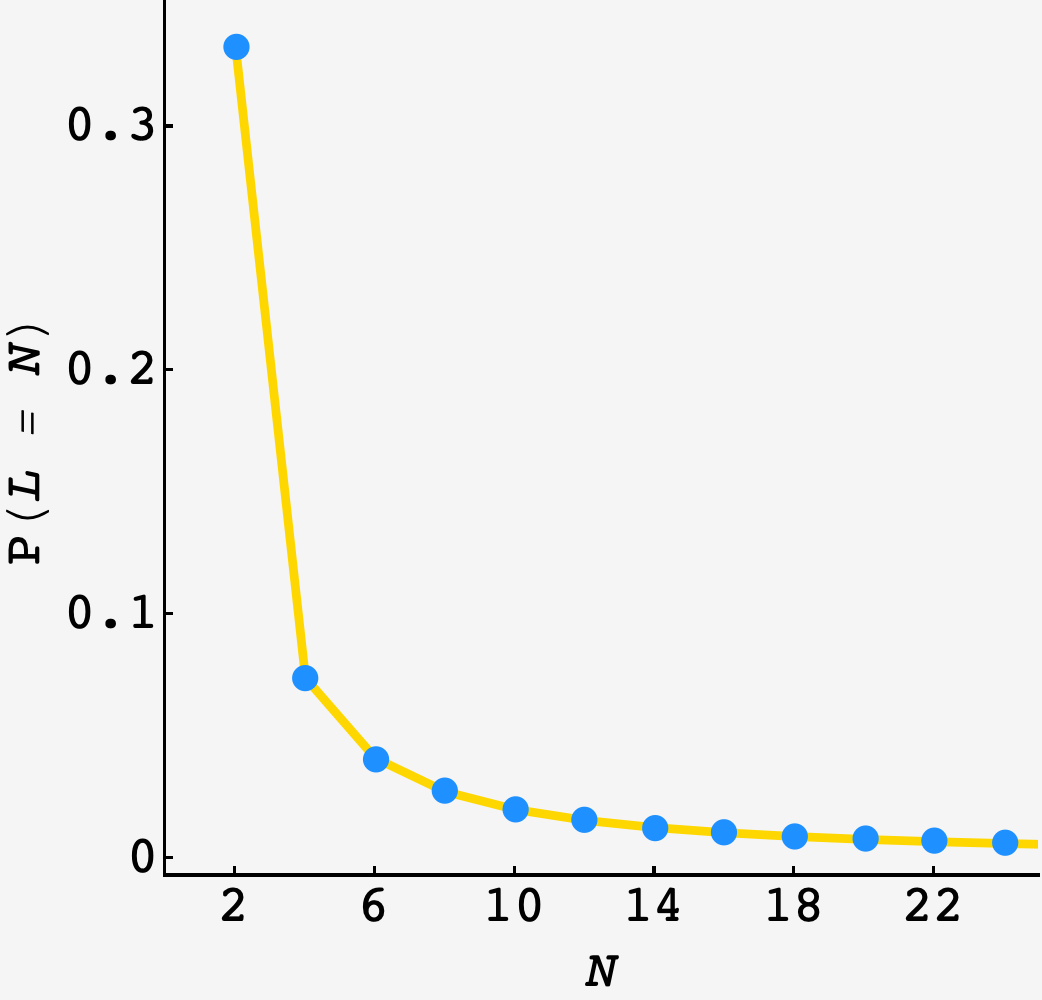

Any $n$ step path on the reduced lattice is a path of length $2n$ on the original, and therefore has probability $1/3^{2n}$ of occurring. If we can count the number of $n$ step paths on the reduced lattice $\omega(n)$, then we will inherit the distribution of path lengths $p(n) = \omega(n)/3^{2n}.$

Count them up

We can count paths with a simple observation: if there is an $(n-1)$ step path to any of my neighbors, then there is an $n$ step path to me. In other words:

\[\omega_i^n = \sum\limits_{j\in\sigma(i)\setminus \boldsymbol{0}} \omega_j^{n-1}.\]The number of $n$-tile paths to me is the sum of $(n-1)$ paths to each of my neighbors. We only want to count first returns to the origin, so we don’t count the origin when it happens to be a neighbor.

With this recursion, we can count $\omega_\boldsymbol{0}^n,$ but we need the base case — the path counts after the first step.

On the reduced lattice, we have $9$ possible moves, formed by all possible pairs of first and second moves on the original lattice. There are $3$ ways to stay put (move in any of the $3$ first move directions followed immediately by the reverse) and $1$ way each to move in each of the $6$ directions on the reduced lattice.

Now, we have everything we need, so let’s code it up:

(* form first moves on the original lattice *)

oddMoves = {Cos[#], Sin[#]} & /@ {π/6, 5 π/6, -3 π/2};

(* reflect to form the second moves on the original lattice *)

evenMoves = ({1, -1} * #) & /@ oddMoves;

(* form the set of moves on the reduced lattice *)

twoStepMoves = Total /@ Tuples[{oddMoves, evenMoves}];

(* initialize ω *)

ω[pt_, 1] := 0;

(* use the two step moves to fill in the base case *)

Do[ω[twoStepMoves[[i]], 1] += 1, {i, 1, Length@twoStepMoves}];

(* one time step recursion over neighbors, excluding the origin *)

ω[pt_, t_] := ω[pt, t] = (

neighbors =

Table[pt - twoStepMoves[[i]], {i, 1, Length@twoStepMoves}];

neighbors = Select[neighbors, # != {0, 0} &];

Return[

Total[ω[#, t - 1] & /@ neighbors]

]

)

The result has good agreement with a $10^7$ round simulation:

With this in hand, we can find the chance that Andy has an unusually long walk during his kitchen sojourn:

\[\begin{align} P(T_\text{kitchen} \gt \langle T\rangle_\text{soccer}) &= 1 - \sum\limits_{n=1}^{10}p(n) \\ &= 1 - \sum\limits_{n=1}^{10}\frac{\omega_\boldsymbol{0}^n}{3^{2n}} \\ &= \frac{173576992}{387420489} \\ &\approx 44.80326\% \end{align}\]