Question: As the Royal Astronomer of Planet Xiddler, you wake up from a dream in which you measured the planet’s radius using a satellite. “How silly!” you think to yourself. “Satellites haven’t even been invented yet!” And so you and another astronomer set out to investigate the curvature of the planet.

The two of you climb two of the tallest towers on the planet, which happen to be in neighboring cities. You both travel 100 meters up each tower on a clear day. Due to the curvature of the planet, you can barely make each other out.

Next, your friend returns to the ground floor of their tower. How high up your tower must you be so that you can just barely make out your friend again?

Solution

The problem doesn’t mention a radius for the planet, but does say that it’s spherical.

The answer will depend on the ratio of the initial height $h_0$ to the radius of the planet $R$. If the planet is say, $1\text{ m}$ in radius, then there may not be any height where the friend in the tower can see the friend on the ground.

Minimal radius for the planet

Without a value for the radius, we can estimate a lower bound. Spheres in space don’t happen by accident, they happen because the gravitation of the body is strong enough to collapse any irregularities that are significant with respect to the length scale of the planet.

Taking granite as a representative material, its maximal compressive strength is $\sigma = 10^8 \text{ N/m}^2$ and its density is about $\rho = 3000 \text{ kg/m}^3.$ If we assume that our protuberance has uniform area $A$ and height $h$, then the total mass of the protuberance is $\rho A h.$

We can estimate the gravitational field of the planet by Newton’s constant times the planet’s mass divided by its prevailing length scale: $g=GM/R.$ The crushing force that the protuberance imparts on its base is the product of these $\left(Mg = \rho A h GM/R\right).$

Equating the maximal compression at the base of the protuberance to the gravitational pull on the protuberance, we get the critical height $h$ at which the protuberance will crack:

\[\sigma A = \rho A h^\ast \dfrac{GM}{R}\]This gets us $h^\ast/R = \sigma/\left(\rho GM\right).$

Since, the mass of the planet is about $\rho R^3$ so we get $h^\ast/R = \dfrac{\sigma}{\rho^2 G R^3}.$

Setting $h^\ast/R \approx 1/100$ as an aesthetic cutoff for being “spherical”, we get

\[\begin{align} R &\approx \sqrt[3]{100\sigma/G\rho^2} \\ &\approx \sqrt[3]{10^2\times 10^8\times 10^{11}/10^6} \end{align}\]or $R\approx 10^5\text{ m}.$

Now you see me, now you don’t

With $R \gtrapprox 10^{5}\text{ m}$ on the table, we can move on to the geometry.

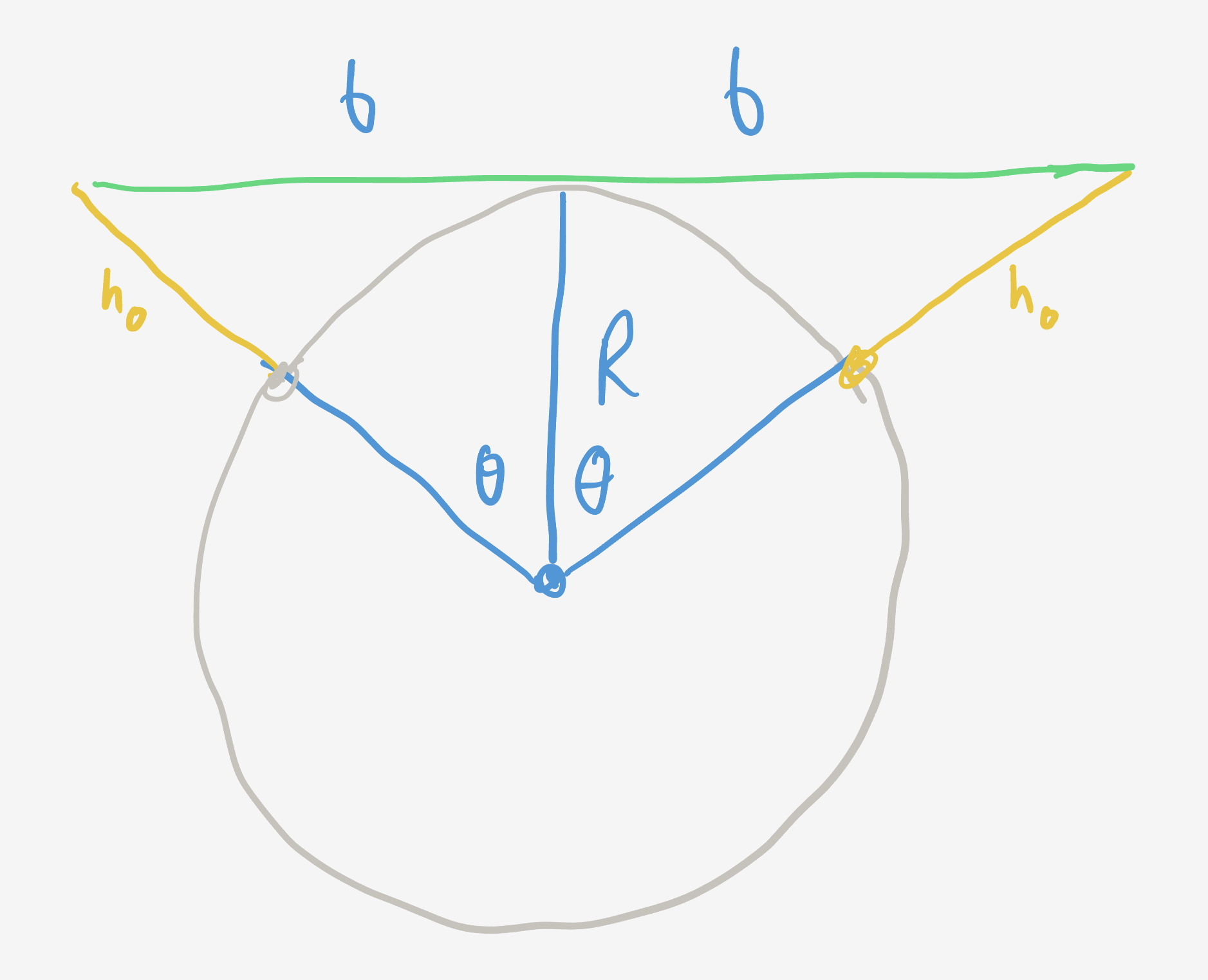

Drawing the initial scenario, we get that $\cos\theta = R/(R + h_0),$ $\sin\theta = b/(R + h_0),$ and $b^2 = (R + h_0)^2 - R^2.$

In the second situation, the friend in the high tower is going to continue moving up the tower. With coordinates centered on the center of the planet, we can describe their path by

In the second situation, the friend in the high tower is going to continue moving up the tower. With coordinates centered on the center of the planet, we can describe their path by

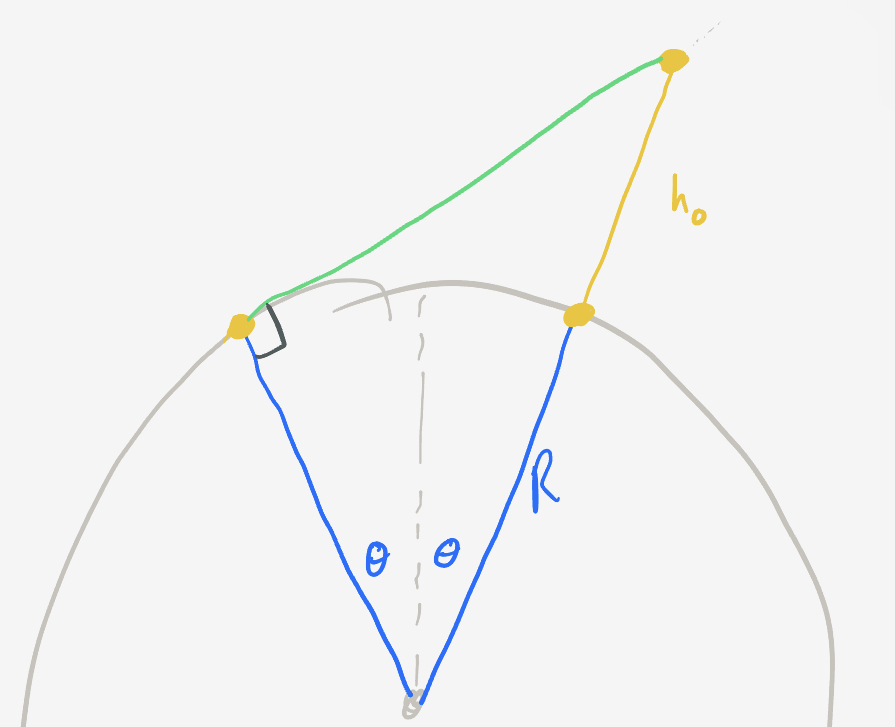

The friend on the ground will have a direct line of sight to the friend in the tower. Since they can just barely see each other, the line of sight will be parallel to the ground where the second friend stands. The slope of the line of sight will be $b/R,$ which can be seen by reflecting the first line across the $y$-axis, and rotating it by $90^\circ$ clockwise. As their initial position is given by $(R\sin\theta, R\cos\theta),$ their line of sight follows the line

\[y_\text{g} = R\cos\theta + \dfrac{b}{R}\left(x_\text{g} + R\sin\theta\right).\]Setting these equal, we can find $x^\ast$ when the paths intersect:

\[x^\ast = \dfrac{R\cos\theta + b\sin\theta}{\dfrac{R}{b} - \dfrac{b}{R}}\]In this second scenario, the friend in the tower will be $(R+h)$ from the center of the planet with coordinates $\left(x^\ast, y^\ast\right):$

\[\begin{align} \left(R + h\right)^2 &= {x^\ast}^2 + {y^\ast}^2 \\ &= \left[1 + \left(\dfrac{R}{b}\right)^2\right]\left(\dfrac{R\cos\theta + b\sin\theta}{\dfrac{R}{b} - \dfrac{b}{R}}\right)^2 \\ &= \left[1 + \left(\dfrac{R}{b}\right)^2\right] \dfrac{\left(\dfrac{R^2 + b^2}{R+h_0}\right)^2}{\left(\dfrac{R}{b}\right)^2\left[1-\left(\dfrac{b}{R}\right)^2\right]^2} \\ &= \dfrac{b^2 + R^2}{R^{-2}\left(R^2 - b^2\right)^2}\left(R + h_0\right)^2 \\ &= \dfrac{R^2\left(R+h_0\right)^4}{\left(R^2 - b^2\right)^2} \\ &= \dfrac{R^2\left(R+h_0\right)^4}{\left[2R^2 - (R+h_0)^2\right]^2} \\ &= \dfrac{R^2\left(R+h_0\right)^4}{(R-h_0)^4}. \\ \end{align}\]So, $ h = R\left(R+h_0)\right)^2/\left(R-h_0\right)^2 - R.$

Since $R \gtrapprox 10^5\text{ m},$ the ratio $h_0/R$ is on the order of $10^{-3}$ and we can safely expand in powers of $h_0/R.$

\[\begin{align} h &= \dfrac{(R+h_0)^2}{R(1-h_0/R)^2} - R \\ &= \dfrac1R (R+h_0)^2(1+h_0/R+\ldots)(1+h_0/R+\ldots) - R\\ &\approx \dfrac1R(R^2 + 2Rh_0 + h_0^2)(1+2h_0/R) - R \\ &\approx \dfrac1R (R^2 + 2Rh_0 + R^2 2h_0/R) - R \\ &= 4h_0 \end{align}\]Where we have kept all terms to first order in $h_0.$ So, for all spherical planets, the friend in the tower would have to go up $4h_0 = 400\text{ m}$ to see the friend on the ground at the base of their tower.