Question: The New York Nicks are facing off against the Brooklyn Naughts. Throughout the entire game, the two teams alternate possession, starting with the Nicks, until both teams have had exactly 100 possessions. For simplicity, assume that each team scores either 0 points or 2 points with each possession. (So don’t worry about 3-pointers, fouls, etc.)

Whenever the game is tied, the team that currently has possession has a 50 percent chance of scoring 2 points. When the game is not tied, the team that is in the lead takes it easy and the team that is behind is more motivated to score. In this case, assume that the team that is behind has a $50+x$ percent chance of scoring, while the team that is ahead has a $50−x$ percent chance of scoring. Here, $x$ is a positive number that is greater than 0 and less than 50.

In preparation for the game, the official scorekeeper (who knows the value of $x$) crunched the numbers and realized the game has a 50 percent chance of being tied at the end of regulation.

In the event that the game is not tied at the end of regulation, what is the probability that each team wins?

Solution

Who is going to win?

First, let’s figure out which side has the natural advantage — is it the team that goes first or the one that goes second?

Once either team gets a two basket lead, the game’s structure is symmetric on either side. But when the game is close, things get interesting.

After one possession, the Nicks can be ahead if they score a basket (even odds), followed by the Noughts missing their basket (less than even odds). The Noughts can be ahead after one possession if the Nicks miss (even odds), followed by the Noughts scoring (even odds). So, after one possession, the advantage is to the Noughts:

\[\overbrace{\text{unlikely}\times\text{even odds}}^\text{Nicks lead} < \overbrace{\text{even odds}\times\text{even odds}}^\text{Noughts lead}.\]This advantage compounds on the next possession. If the Nicks are up by a basket, the game can return to a tie if the Nicks miss (better than even odds, since they’re ahead), and then the Noughts make (better than even odds, since they’re underdogs). On the other hand, the Noughts can lose their one basket lead if the Nicks make (better than even odds), followed by the Noughts missing (even odds). Once again, the advantage is to the Noughts:

\[\overbrace{\text{likely}\times\text{likely}}^\text{Nicks blow lead} > \overbrace{\text{even odds}\times\text{likely}}^\text{Noughts blow lead}.\]All in all, the team that goes second will win a greater fraction of the games.

The setup

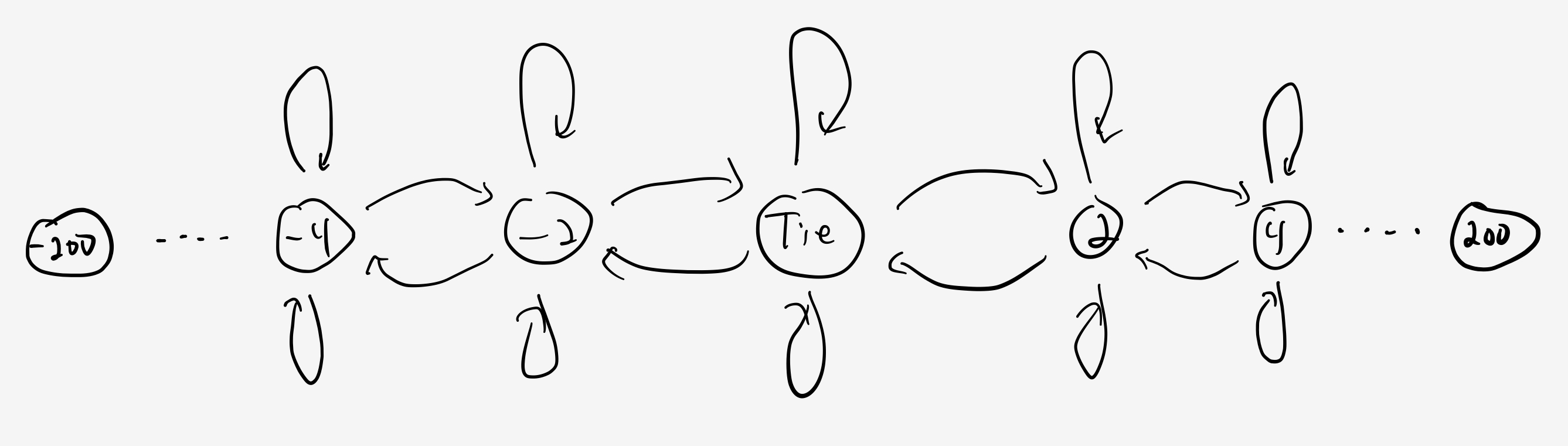

The game alternates turns between the Nicks and the Noughts. On first read, it may seem like we need to model things that way. But it’s simpler to zoom out and think about pairs of turns, or “rounds”. Modeled this way, in each round, the game can move one step to the left, stay put, or move one step to the right.

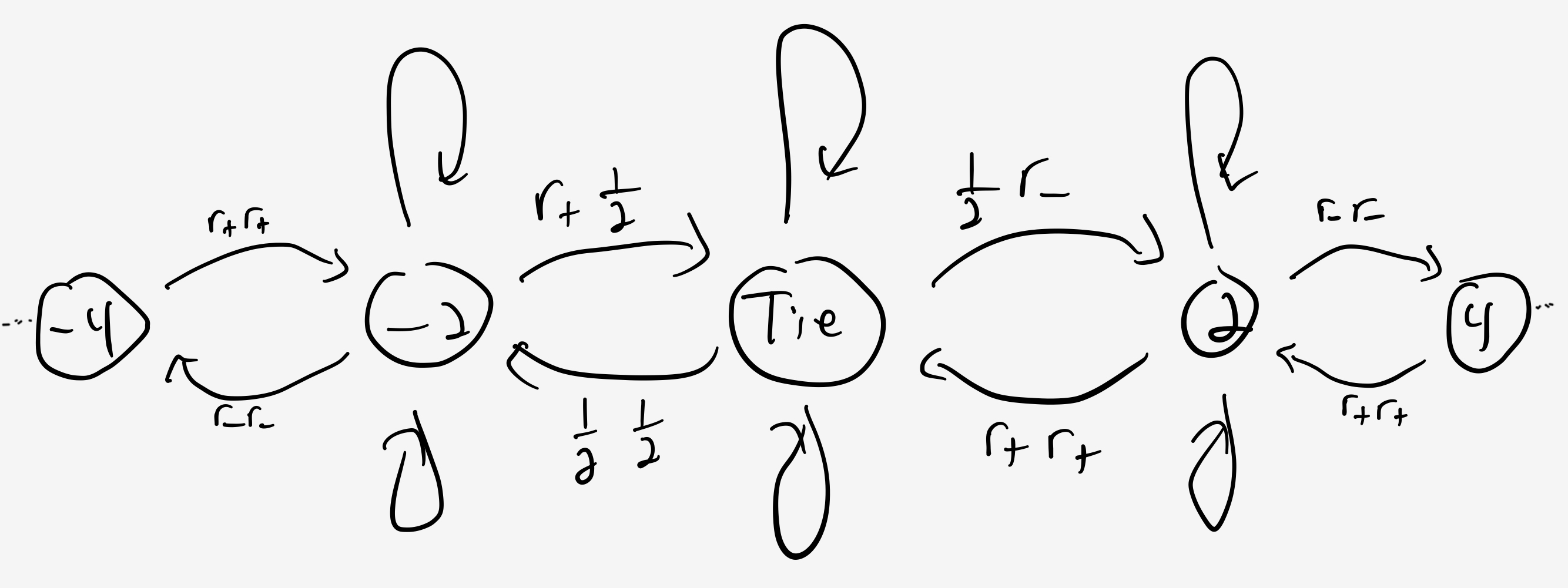

This gives us a board like:

The probability of a tie is equal to $P(\text{tie}).$ The first player wins if the game ends anywhere to the right of the origin, so the probability that the first player wins is equal to

\[S_+ = \sum_{n=1}^{100} P(n)\]In the same way, the probability that the second player ends up winning is

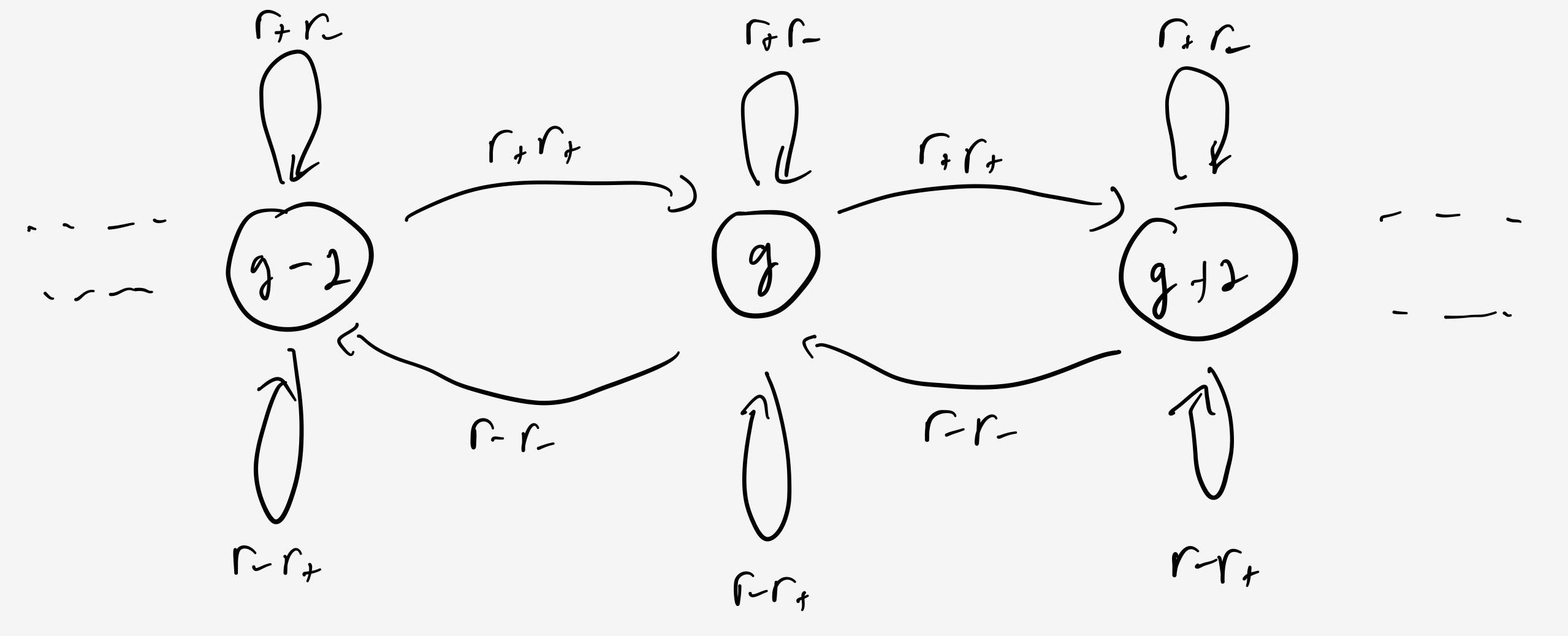

\[S_- = \sum_{n=-100}^{-1} P(n)\]Away from the origin, the transition rates are simple. For the game to move away from the origin in a turn, the team with disadvantage has to make its shot followed by a miss from the team with advantage. This has probability

\[r_-(1-r_+) = r_-^2.\]Similarly, for the game to move back toward being tied, the team with disadvantage needs to miss its shot, followed by a make from the team with advantage. This has probability

\[r_+(1-r_-) = r_+^2.\]This symmetry is broken near the origin, which is what gives the problem its structure.

Starting from a tie, the game can move to $g = 2$ if the Nicks make their shot, followed by a miss from the advantaged Noughts. Because the game is tied when the Nicks shoot, the probability of a make is $\frac12.$ The probability of the Nought’s miss is $(1-r_+) = r_-.$ So, the overall probability is $\frac12 r_-.$

The game can move back from $g = 2$ to a tie if the disadvantaged Nicks miss followed by a make by the advantaged Noughts. So, the probability is $r_+^2.$

Following the same sort of reasoning, the rates to and from $g=-2$ are $\frac12\frac12$ and $r_+\frac12,$ respectively.

So, in the wings, the game looks like

and near the origin, the game looks like

The big picture

We can build intuition about the dynamics by inspecting the diagrams.

-

Because score gaps incentivize the underdog and relax the leader, the game feels pressure to stay near the origin. This tells us that the distribution will have thin tails and, also, that the distribution will quickly become constant in time.

-

Comparing either side, the wings have identical structure. So, up to an overall constant, we expect the distributions to be symmetric, e.g. $P(-2) = \gamma P(2),$ $P(-4) = \gamma P(4).$ As a result, $S_- = \gamma S_+.$

-

As we move away from the origin, the game looks the same, whatever the score, and each step sees the same transition rate imbalance, $r_-^2/r_+^2 < 1.$ We expect the probability to decay like some decreasing function $f(r_-^2/r_+^2).$

With these insights on the table, we can analyze the equations for concrete results, starting in the wings. Given the probability $P_{t-1}(g)$ of a score gap $g$ after $t-1$ rounds, its change in the next round is equal to

\[\Delta = r_-^2P_{t-1}(g+2) + r_+^2P_{t-1}(g-2) - (r_+^2 + r_-^2)P_{t-1}(g)\]We argued above that the games become constant in time — applying the equilibrium condition, this becomes

\[0 = r_-^2P(g+2) + r_+^2P(g-2) - (r_+^2 + r_-^2)P(g)\]This equation is a two-step recursion, but it’s really a one step recursion in disguise. We can see this from a slight rearrangement, and factoring using a shift $\mathbb{E}_g,$ (that acts on functions of $g$ like $\mathbb{E}_g f(g) = f(g+2)$):

\[\begin{align} 0 &= r_-^2\left[P(g+2) - P(g)\right] - r_+^2\left[P(g) - P(g-2)\right] \\ &= \left(\mathbb{E}_g-1\right)\left[r_-^2P(g) - r_+^2P(g-2)\right]. \end{align}\]This shows that

\[\boxed{ P(g) = \begin{cases} \left(\dfrac{r_-}{r_+}\right)^2 P(g-2) & g < 0 \\ \left(\dfrac{r_-}{r_+}\right)^2 P(g+2) & g > 0 \end{cases} }\]which is what we intuited above. This immediately gets us $S_-:$

\[\boxed{ \begin{align} S_- &= P(-2) + P(-4) + P(-6) + \ldots \\ &= \left[1 + \frac{r_-^2}{r_+^2} + \left(\frac{r_-^2}{r_+^2}\right)^2 + \ldots\right] P(-2) \\ &= \dfrac{P(-2)}{1-r_-^2/r_+^2} \end{align} }\]Similarly,

\[\boxed{S_+ = \dfrac{P(2)}{1-r_-^2/r_+^2}.}\]Solving the system

Now we can analyze $P(-2).$ Following the diagram, the change in $P(-2)$ from one moment to the next is

\[\begin{align} 0 &= \frac{1}{2^2} P(0) + r_+^2 P(-4) - \left(\frac12 r_+ + r_-^2\right)P(-2) \end{align}\]Using the one-step recursion, this becomes

\[\boxed{P(-2) = \dfrac{P(0)}{2r_+}}\]The same analysis for $P(2)$ gets

\[\left[1 - r_-^2 -2r_-r_+\right]P(2) = \frac12 r_- P(0)\]Here we can use the fact that $r_- + r_+ = 1$ to get $r_-^2 + r_+^2 + 2r_-r_+ = 1,$ so that the above simplifies to

\[\boxed{P(2) = \dfrac{r_-}{2r_+^2} P(0)}.\]Now we can solve for $P(0):$

\[\begin{align} 1 &= P(0) + S_- + S_+ \\ &= P(0) + \dfrac{P(-2)}{1 - \left(r_-/r_+\right)^2} + \dfrac{P(2)}{1 - \left(r_-/r_+\right)^2} \\ &= \left(1 + \dfrac{1}{2r_+}\dfrac{r_+^2}{r_+^2 - r_-^2} + \dfrac{r_-}{2r_+^2}\dfrac{r_+^2}{r_+^2 - r_-^2}\right)P(0) \\ &= \left(1 + \frac12 \dfrac{r_+ + r_-}{r_+^2 - r_-^2}\right)P(0) \\ &= \left(1 + \frac12 \dfrac{1}{r_+ - r_-}\right)P(0) \end{align}\]or, restoring the values of $r_-$ and $r_+,$

\[\boxed{P(0) = \dfrac{4x}{1+4x}}.\]Since we’re told that $P(0) = \frac12,$ $x$ must be $\frac14.$ Using the relationship between $P(-2)$ and $P(0),$ we get

\[\begin{align} S_- &= P(-2)\dfrac{r_+^2}{r_+^2 - r_-^2} \\ &= \frac{P(0)}{2r_+} \dfrac{r_+^2}{r_+^2 - r_-^2} \\ &= \frac12 P(0)\dfrac{r_+}{r_+ - r_-} \\ &= \frac12\dfrac{4x}{1+4x}\dfrac{\frac12 + x}{2x} \end{align}\]or

\[\boxed{S_- = \frac{1+2x}{2+8x}}\]The same calculation for $S_+$ gets

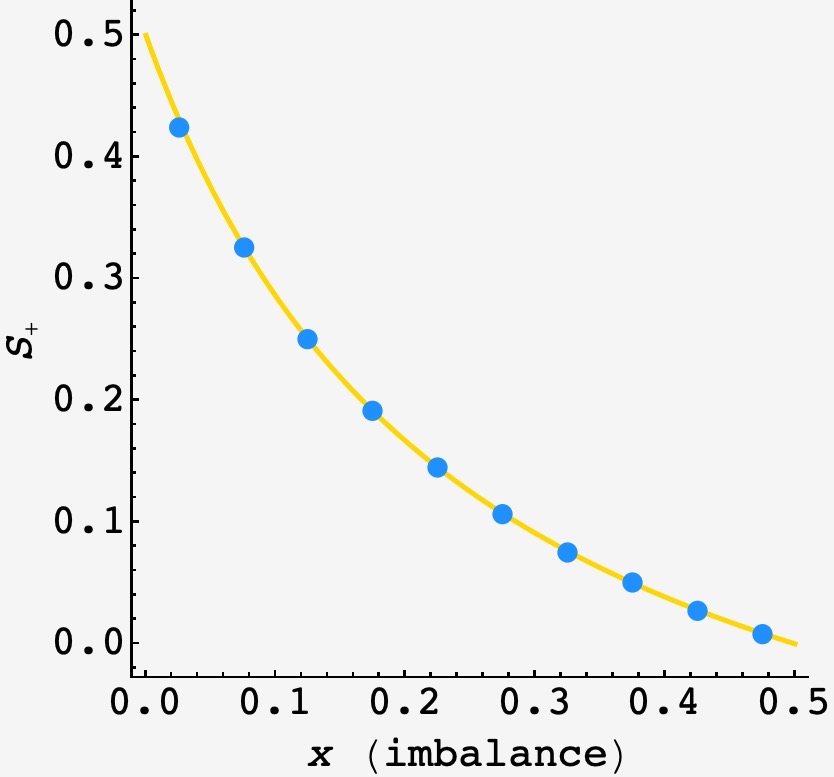

\[\boxed{S_+ = \dfrac{1-2x}{2 + 8x}}.\]Plotting this against an $N=10^6$ round simulation for $S_+,$ we see

This result makes sense:

- When $x=0,$ there is no built in advantage to going first, and the game has even odds.

- Likewise, when $x=\frac12,$ every point gap opened up by the Nicks is immediately closed by the Noughts, who are guaranteed to score when they’re down. This means that the Nicks can never hold a lead, they can only tie, so $S_+$ goes to $0.$

Comparing $S_-$ and $S_+$ we see that $S_-/S_+ = (1+2x)/(1-2x),$ which is $3$ for $x = \frac14.$

So, given that the game wasn’t a tie, there’s a $75\%$ chance the Noughts won the game.

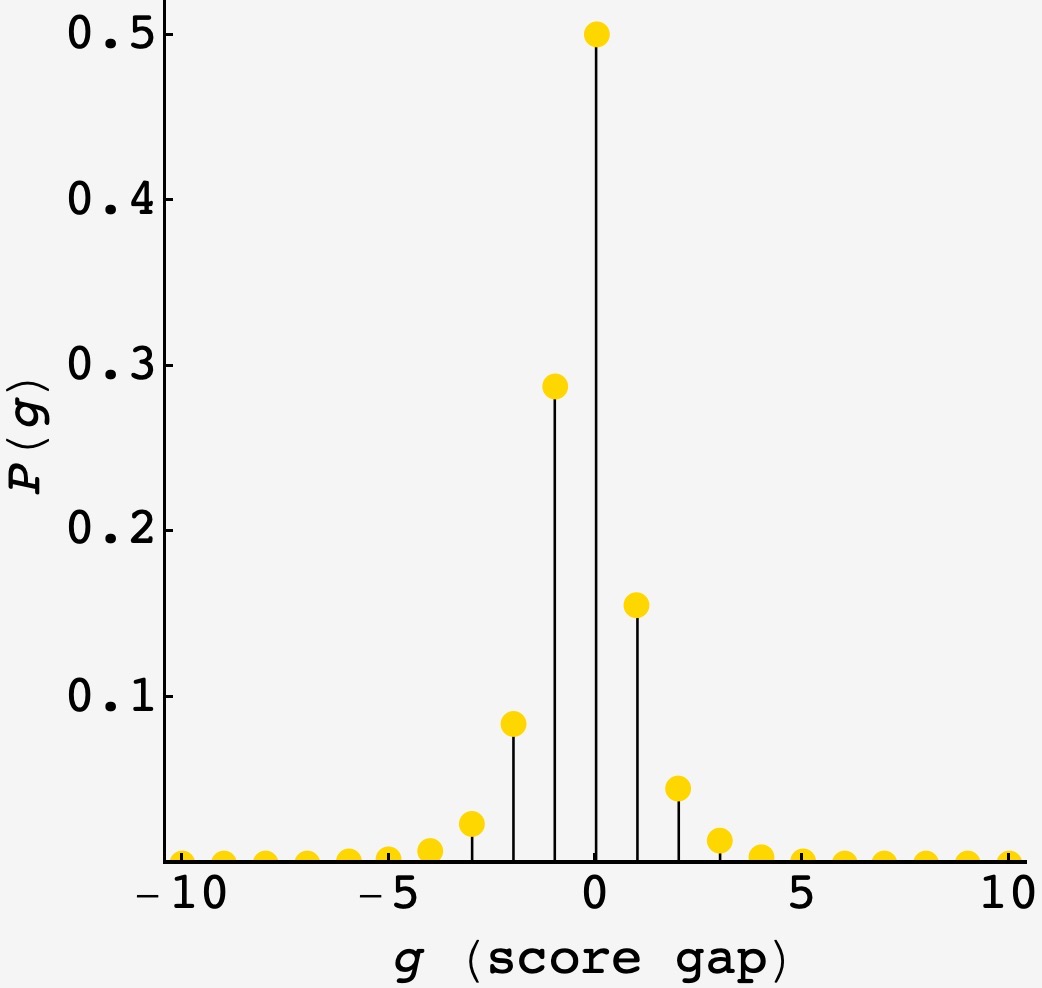

From these ingredients, we can get the whole steady state distribution of score gaps $P(g),$

\[P(g) = \begin{cases} \dfrac{4x}{1+4x}\dfrac{1}{1 + 2x}\left(\dfrac{\frac12 - x}{\frac12 + x}\right)^{-2(g+1)} & g < 0 \\ \dfrac{4x}{1+4x} & g = 0 \\ \dfrac{4x}{1+4x}\dfrac{\frac12 - x}{2(\frac12+x)^2}\left(\dfrac{\frac12 - x}{\frac12 + x}\right)^{2(g-1)} & g > 0 \end{cases}\]Plotting the result (for a less-compressed value of $x = 0.15$) we see that it has all the essential features we anticipated.

- it’s concentrated around the middle,

- it’s thin-tailed,

- it’s symmetric about $g=0$ up to a constant scaling factor: