Question: Four gnomes are trying to escape from a room. Guards have placed a hat on each gnome’s head, and each hat is one of three colors: red, yellow or blue. The four gnomes are arranged at the vertices of a square, with an obstacle in the middle. Each gnome can see the hats on the heads of those on adjacent vertices of the square, but they cannot see the hat of the gnome diagonally across from them. They also do not know the color of the hat on their own head. Each gnome must guess the color of the hat on their own head. If at least one gnome guesses correctly, they can all escape the room together. No communication is allowed once the hats are placed on their heads, but they can coordinate on a strategy beforehand. They also know how they will be arranged in the circle.

How can they be guaranteed to escape the room?

Solution

Before looking for solutions, we can lay down some basic facts.

The facts

Each gnome will guess correctly in exactly $h^{n-1} = 27$ of the $h^n = 81$ potential cases, regardless of how they design their policy.

This is because each player makes the same guess for each pair of hat colors they can see, which have no correlation with the hat on their head.

An immediate corollary is that, in all, the players will make $h^{n-1} \times n = 108$ correct guesses. So, at least in number, there are more than enough correct guesses to distribute $1$ to each of the $h^n = 81$ possible cases. If there are more hat colors than people, then full survival is impossible.

The control we can exert is how the correct responses are distributed.

Strategies

A simple example helps illustrate this:

Two players with two hat colors — it is either the case that the two players have the same hat color, or they have different hat colors. So, if Player A always guesses the same as their partner’s hat and Player B always guesses the opposite of their partner’s hat, then at least one of them will be right in every round that’s played.

We are trying to find a similar sort of structure here.

No strategy

Without any structure (i.e. the gnomes use random strategies) they will survive in, on average, $65$ of the $81$ cases. The first gnome makes $27$ correct guesses which is a third of cases. So the second player will make, on average, $18$ of their correct guesses in cases where the first player is wrong. Together, $18$ and $27$ make $45$ which is $5/9^\text{th}$s of all cases, so the third player will make correct guesses in $12$ cases where the first two players are wrong. Finally, fourth player will be correct in $8$ novel cases. all together, $27+18+12+8 = 65.$

Similarly, the gnomes will survive in no fewer than $45$ of the $81$ cases.

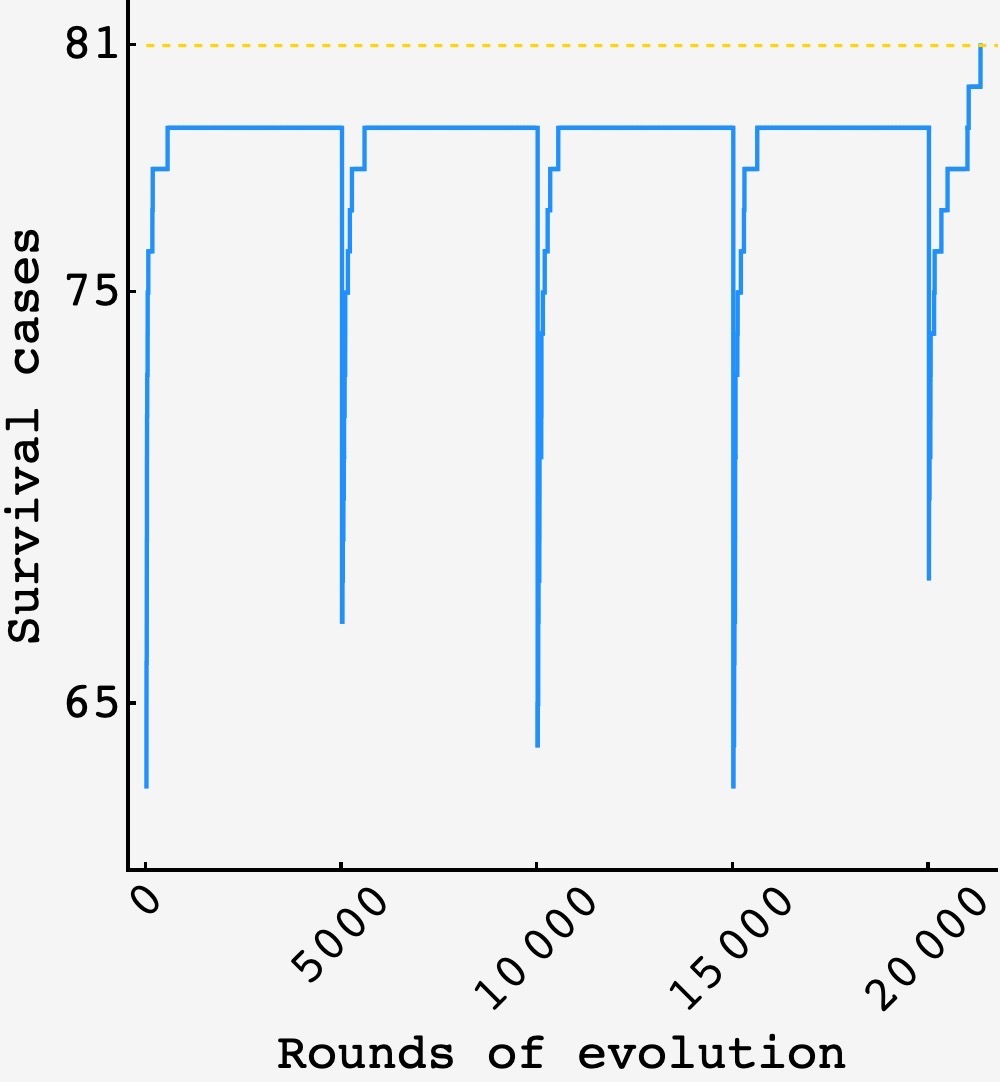

Finding a nice breakdown did not yield to analysis, so we turned to biology. Essentially, the gnomes pick a random strategy (a map from the $3\times3 = 9$ hat pairs they can see to a prediction for their own hat) and then figure out how many cases they would currently survive in. They then pick a random gnome among them to mutate a random row in their map. If this change doesn’t lower the number of cases they survive in, then they accept the change, otherwise they reject it. Then the process starts again.

This has the potential to be a very quick discovery process because there is no connection between one gnome being correct and another being wrong. Progress is progress is progress.

It’s always possible that the gnomes pick a slow region of strategy space to start in, so if they go $5000$ mutations without hitting $81$ they all repick a random strategy and start over.

In a few thousand mutations, the gnomes find a suitable strategy and achieve $100\%$ survival, as desired.

The strategy (one of many) they found is

\[\begin{array} \\ \text{View} & \text{Player 1} & \text{Player 2} & \text{Player 3} & \text{Player 4} \\ \tt (r, r) & \tt y & \tt y & \tt r & \tt g \\ \tt (r, g) & \tt y & \tt g & \tt g & \tt r \\ \tt (r, y) & \tt r & \tt r & \tt r & \tt y \\ \tt (g, r) & \tt r & \tt g & \tt g & \tt g \\ \tt (g, g) & \tt y & \tt r & \tt y & \tt g \\ \tt (g, y) & \tt g & \tt r & \tt r & \tt r \\ \tt (y, r) & \tt g & \tt y & \tt y & \tt r \\ \tt (y, g) & \tt r & \tt y & \tt y & \tt y \\ \tt (y, y) & \tt g & \tt g & \tt g & \tt y \end{array}\]The full evolutionary algorithm in Python:

import random

import itertools

import copy

colors = ['r', 'g', 'y']

strategies = [

{_ : random.choice(colors)

for _ in itertools.product(colors, repeat=2)}

for _ in range(4)

]

# list of all possible combination of hat colors for 4 gnomes

cases = list(itertools.product(colors, repeat = 4))

# list of all possible pairs of viewable hats for two gnomes

player_views = list(itertools.product(colors, repeat = 2))

def evaluate_round(case, strategies):

P1_pred = strategies[0][(case[1], case[3])] == case[0]

P2_pred = strategies[1][(case[0], case[2])] == case[1]

P3_pred = strategies[2][(case[1], case[3])] == case[2]

P4_pred = strategies[3][(case[0], case[2])] == case[3]

return (1 if any([P1_pred, P2_pred, P3_pred, P4_pred]) else 0)

def score_current_strategies(strategies):

return sum(evaluate_round(case, strategies) for case in cases)

scores = []

for round in range(100000):

# if 5000 rounds have elapsed, reset the search

if round % 5000 == 4999:

strategies = [

{_ : random.choice(colors)

for _ in itertools.product(colors, repeat=2)}

for _ in range(4)

]

current_score = score_current_strategies(strategies)

# pick a player whose strategy we'll mutate

strategy_to_mutate = random.randint(0,3)

# pick the specific view we're mutating

case_to_mutate = random.choice(player_views)

temp_strategies = copy.deepcopy(strategies)

temp_strategies[strategy_to_mutate][case_to_mutate] = random.choice(colors)

temp_score = score_current_strategies(temp_strategies)

if temp_score >= current_score:

strategies = temp_strategies

current_score = temp_score

scores.append(current_score)

if temp_score == 81:

break