Question: In the Robot Swimming Trials, $3N$ identical robots compete for $N$ equivalent spots in the finals by swimming $N$ races. Each robot precommits to spending a certain amount of its fuel in each race. After all the races are run, the spots in the finals are given to the winners of the races, moving from the fastest winner to the slowest. (Once a robot wins a race, it is ineligible to win another race.) A robot’s speed is strictly increasing in the amount of fuel it spends, and ties are broken by randomly choosing the winner among the robots that have spent the same amount of fuel.

Mathematically speaking, the $3N$ robots each submit a strategy, which is an $N$-tuple of nonnegative real number “bids” summing to $1,$ representing the fuel burned in each of the $N$ races. The winners of the races are then determined from the highest bid (across all races and all robots) on down, with ties broken randomly. Once a robot wins a race their other bids are deleted, so we are guaranteed to get $N$ distinct qualifiers for the finals.

Over the storied history of the RST, the metagame settled into what was widely believed to be the Nash equilibrium: each robot uniformly randomly selects a race and devotes all of their fuel to it. Let’s call this the discrete strategy. However, rumors are circulating that this conventional wisdom is not entirely accurate: for a large enough $N,$ the discrete strategy is not the Nash equilibrium. You’ve been tasked to find two pieces of information:

What is the smallest $N$ for which the trial does not have the discrete strategy as the Nash equilibrium?

For this $N,$ if the other $(3N-1)$ robots naively play the discrete strategy and your robot plays optimally (exploiting this knowledge of your opponents’ strategies), with what probability $p$ will you make the finals?

Solution

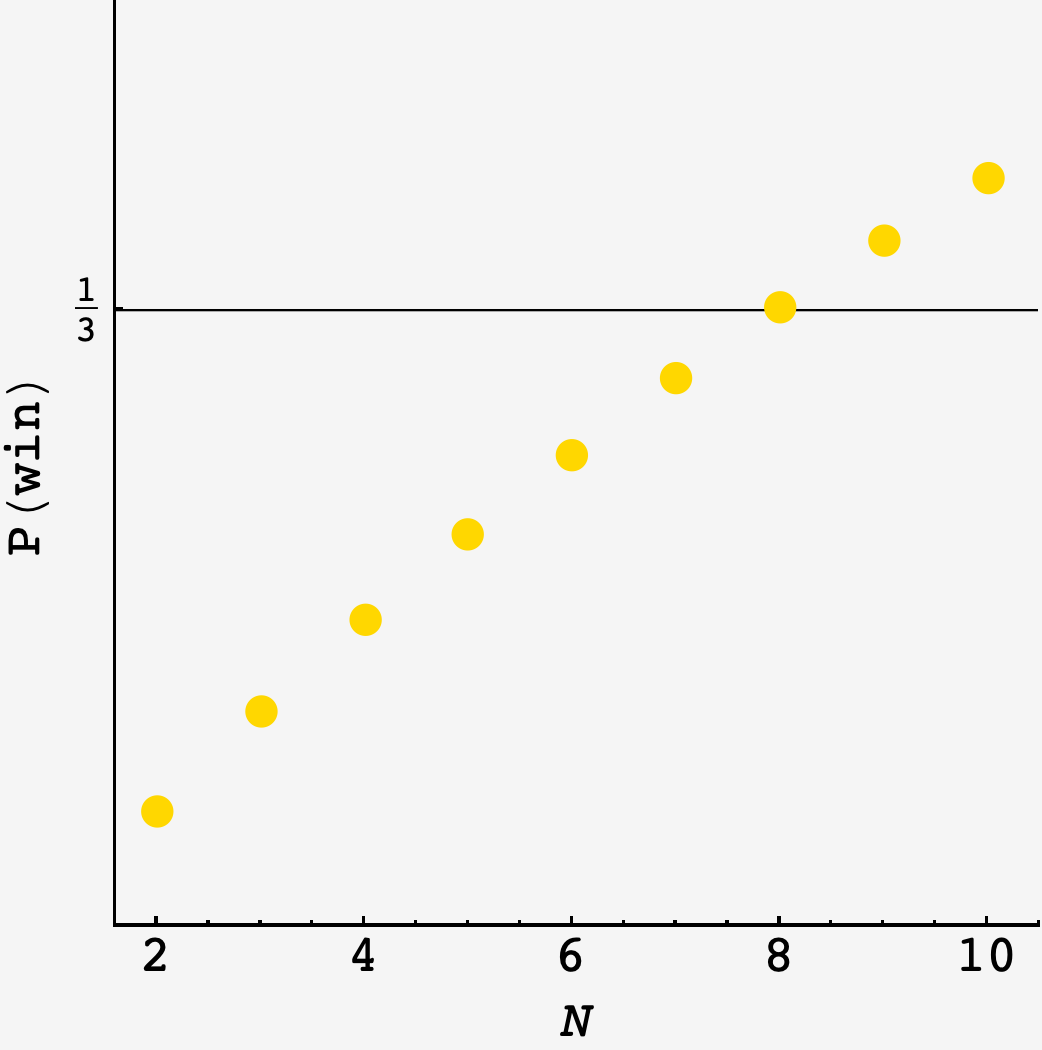

While the discrete strategy reigns as the Nash equilibrium, there are $3N$ racers and $N$ distinct winners of the $N$ races, so the chance for any given player to win is $p=\frac13.$

Disturbing the equilibrium

The discrete strategy is all-or-nothing, so any departure from it will lose a race with discrete competition.

The only hope for a dissenter to win is to put fuel on a race that nobody else does. Any non-zero amount will do in an empty race, so the dissenter puts a non-zero amount on every race.

Chance to win

As the number of races grows, it should get easier for the system to fluctuate into a state where one race goes empty among the $\left(3N-1\right)$ Nash equilibrists. The question is, when do the dissenter’s prospects overcome the equilibrists’?

The dissenter wins if at least one lane is empty. But we need to avoid doublecounting — the chance for lane $1$ to be empty includes the case where lane $2$ is also empty, and vice versa.

The chance that at least one lane is empty, is

\[P(\text{lane 1 empty} \cup \text{lane 2 empty} \cup \ldots \cup \text{lane }N\text{ empty}),\]which isn’t so useful, since unions are hard to calculate. Intersections are easy, though, and we can break it up into disjoint intersections.

If we had just two events, then the chance that one or the other happens is the sum of their individual probabilities less the probability that they both happen

\[P(A\cup B) = P(A) + P(B) - P(A\cap B).\]We can apply this iteratively to reduce each union in turn (taking $A = \left(1\cup 2\right)$ and $B=3$ to begin)

\[\begin{align} P(1\cup 2\cup 3) &= P(1\cup 2) + P(3) - P((1\cup 2)\cap 3) \\ &= P(1) + P(2) - P(1\cap 2) + P(3) - P((1\cap3)\cup(2\cap3)) \\ &= P(1) + P(2) + P(3) - P(1\cap2) - \left[P(1\cap3) + P(2\cap3) - P(1\cap2\cap3)\right] \\ &= P(1) + P(2) + P(3) - P(1\cap2) - P(1\cap3) - P(2\cap3) + P(1\cap2\cap3) \\ &= \binom{3}{1}P(\text{one lane empty}) - \binom{3}{2}P(\text{two lanes empty}) + P(\text{three lanes empty}) \end{align}\]In other words, we sum the chance for all single lanes to be empty, then subtract the chance that any two lanes are empty, then add the chance that any three lanes are empty, and so on, up until the chance that all $3N$ lanes are empty.

The probability that all of the equilibrists avoid $j$ particular races is $\left(\frac{N-j}{N}\right)^{3N-1},$ and there are $\binom{N}{j}$ ways to pick $j$ races to avoid.

Putting it all together, this becomes

\[\begin{align} P(\text{a lane empty}\rvert N) &= P\left(\bigcup\limits_{i=0}^{N}i\text{ empty}\right) \\ &= \sum\limits_{j=1}^{N-1}\binom{N}{j}\left(\frac{N-j}{N}\right)^{3N-1}(-1)^{j+1} \end{align}\]which first overtakes the equilibrists’ chance $p=\frac13$ when there are $8$ races: