Question: after a life of flipping fair coins, you’ve had enough. Your new mission is to construct elaborate and worthless schemes to extract virtual fair coins out of $3$ flips of a crooked one. Ever the positivist, you want to know just how many crooked coins there can be that suit your campaign. For how many values of $p$ can a fair coin be simulated using no more than $3$ flips?

Solution

Von Neumann’s probabilistic coin flip rests on the fact that the probability of $\mathbf{HT}$ and the probability of $\mathbf{TH}$ are both equal to $p(1-p).$ But it ignores two outcomes — $\mathbf{HH}$ and $\mathbf{TT}.$ Those terms are important if we want to simulate a fair coin in a finite number of flips.

Distilling the problem

We want to find an exhaustive set of outcomes that can be partitioned into two groups each with probability $1/2.$

Taking all the outcomes for $3$ coin flips, we get the probabilities

\[\{\overbrace{\mathbf{HHH}}^{p^2}, \overbrace{\mathbf{HHT}}^{p^2(1-p)}, \overbrace{\mathbf{HTH}}^{p^2(1-p)}, \overbrace{\mathbf{HTT}}^{p(1-p)^2}, \overbrace{\mathbf{THH}}^{(1-p)p^2}, \overbrace{\mathbf{TTH}}^{(1-p)^2p}, \overbrace{\mathbf{THT}}^{(1-p)^2p}, \overbrace{\mathbf{TTT}}^{(1-p)^3}\}.\]Some basics

Of these, only $p^3$ and $(1-p)^3$ can eclipse $1/2$ on their own (at $ p = 1/\sqrt[3]{2}$ and $p = 1-1/\sqrt[3]{2}$). The maximum values of $p^2(1-p)$ and $p(1-p)^2$ are just $4/27.$

If we group some of the other terms with $p^3$ ($\mathbf{HHH}$), it will still hit $1/2$ but at a $p > 1/\sqrt[3]{2},$ i.e. it will be pushed toward the middle.

For example, if we group $\mathbf{HHH}$ and $\mathbf{THT}$ as our new “heads”, they’ll have total probability $p^3 + p(1-p)^2$ which hits $1/2$ at $p^* \approx 0.77184.$

The same is true of $(1-p)^3$ ($\mathbf{TTT}$), but any polynomial anchored by $p^3$ can be converted into a polynomial anchored by $(1-p)^3$ through the substitution $p \rightarrow (1-p).$

If the partition containing $p^3$ contains $n$ elements, then the complementary partition contains $2^3 - n$ elements. This means we can restrict our attention to partitions of size $4$ or less. Also, all even partitions (sets of size $4$) cross $1/2$ at $p=1/2,$ which means we can further restrict our attention to sets of size $3$ or less.

Finally, if a set contains $p^3$ and $(1-p)^3$ then it will cross $p = 1/2$ twice (and it cannot generate a second partition since $p^3$ and $(1-p)^3$ are in the same polynomial).

Some counting

So, the question is how many ways can we pair the other terms with $p^3.$

There are $\binom{2}{2} + \binom{2}{1} + \binom{2}{0}$ ways to pair $p^3$ with $2$ or fewer distinct cross terms ($p^2(1-p)$ or $p(1-p)^2$) as well as $2$ ways to pair it with a pair of the same kind of cross term. These kinds of polynomials will each generate a root and their counterpart (found by the $p\rightarrow (1-p)$ substitution) will generate another.

There are also polynomimals that contain both $p^3$ and $(1-p)^3$ (and therefore have no counterpart via the $p\rightarrow (1-p)$ substitution). There are $\binom{2}{1} + \binom{2}{0}$ of these, each of which has $2$ distinct roots.

Altogether this makes for

\[\begin{align} S &= 2\times\left(\binom{2}{2} + \binom{2}{1} + \binom{2}{0} + 2 + \binom{2}{1} + \binom{2}{0}\right) \\ &= 2\times 6 + 2\times 3 \\ &= 18 \end{align}\]distinct roots.

Finally, we neglected even partitions, all of which cross $1/2$ at $p=1/2,$ so we have to add one additional value of $p$ making

\[\boxed{S^\prime = 18 + 1 = 19}.\]Seeing the forest

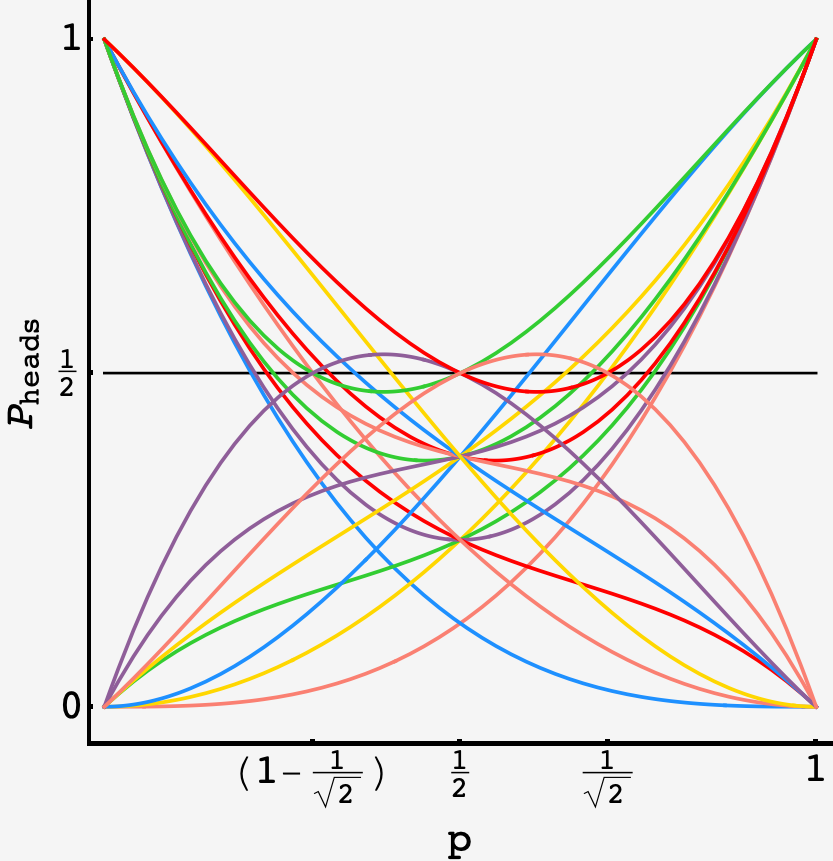

We can visualize the polynomials for the $18$ sets that support a fair coin constructions for a “bent” value of $p$:

The $18$ polynomials that achieve $P_\text{head} = 1/2$ at $p$ away from $1/2.$

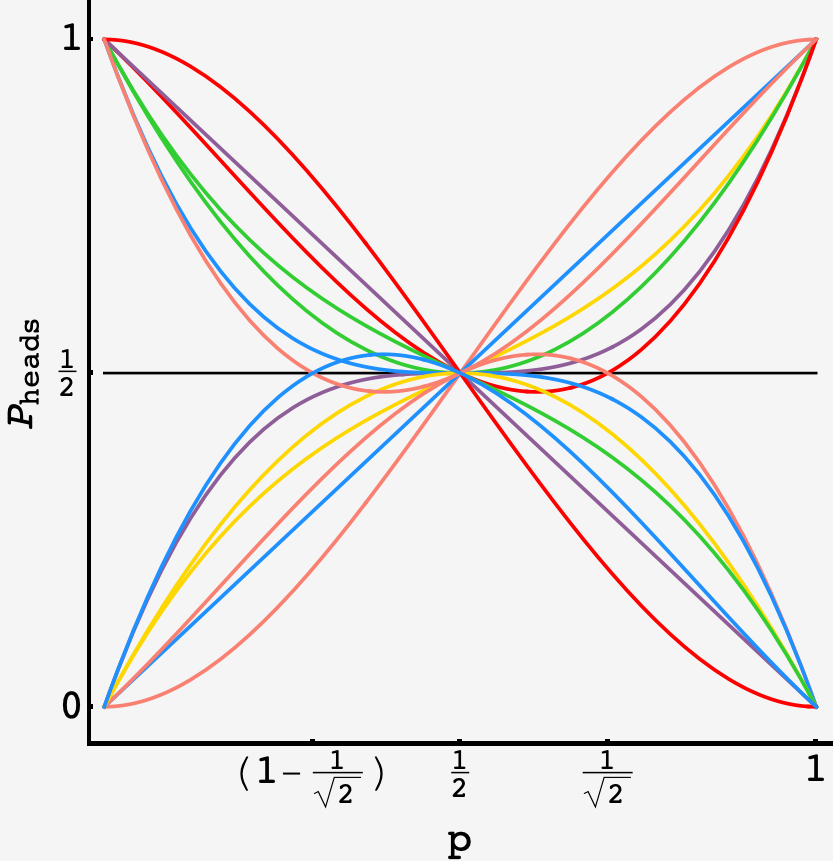

as well as the polynomials for sets that permit constructions for the trivial value of $p=1/2$:

The various polynomials that achieve $P_\text{head} = 1/2$ at $p = 1/2.$ Some of these repeat the root at $P = 1/\sqrt{2}$ and $\left(1-1/\sqrt{2}\right).$

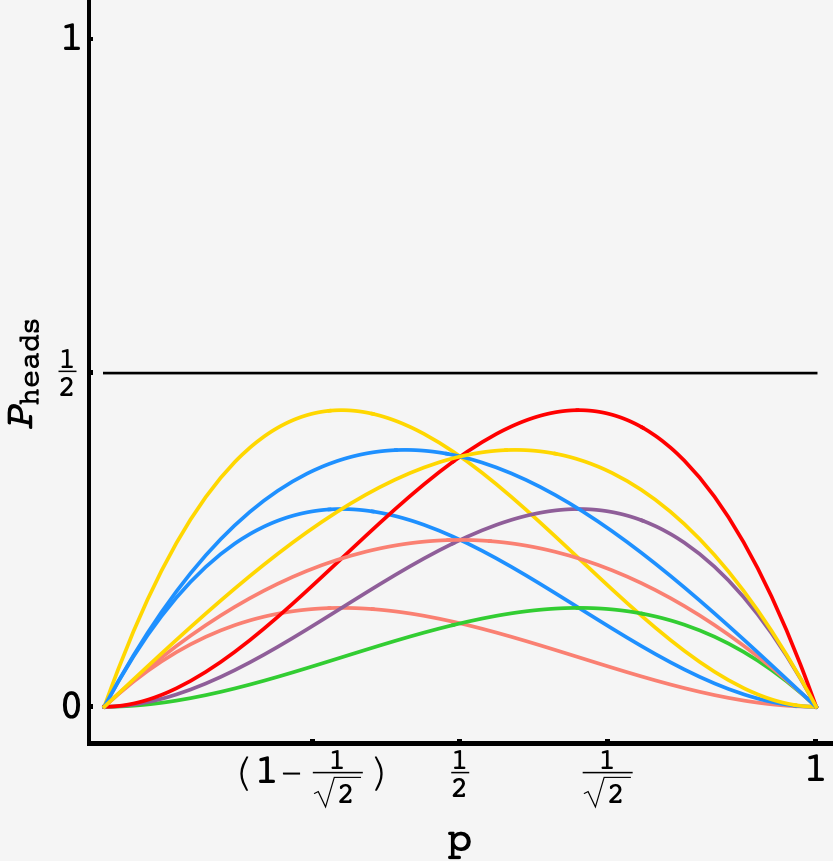

Finally, the polynomials for sets that permit constructions for no values of $p,$ fair or otherwise.

The various polynomials that can’t achieve $P_\text{head} = 1/2$ for any value of $p.$

Fewer flips?

It might seem like we’ve missed some cases, for example,

\[\{\mathbf{HHH}, \mathbf{TH}\}\times\{\mathbf{HT},\mathbf{HHT},\mathbf{TT}\}\]is a valid set that crosses $1/2$ at $p\approx 0.64780.$ However, that’s because it’s a collapse over the marginal distributions in the partition

\[\{\mathbf{HHH}, \overbrace{\mathbf{THT}, \mathbf{THH}}^\mathbf{TH}\}\times\{\overbrace{\mathbf{HTH}, \mathbf{HTT}}^\mathbf{HT}, \mathbf{HHT}, \overbrace{\mathbf{TTT},\mathbf{TTH}}^\mathbf{TT}\}.\]As it turns out, every partition that can be formed with mixes of $2$ and $3$ flip events are just collapses of partitions of the set of $3$ flip events. So, $19$ is all there is.